Tulsa, Oklahoma, like many American cities vying for national attention as a contending innovation hub to attract those straying from Silicon Valley types, has been quietly building a business ecosystem of the future. Equipped with name-brand companies like Amazon and American Airlines, and venture capital firms like Atento and i2E Management, Tulsa’s business community isn’t lacking in momentum following its five-year economic development plan centered around the city’s future which even saw Oklahoma with a reportedly $38 million in venture capital deal flow in 2020.

But Tulsa’s business dealings haven’t held water against a much murkier conversation that has dominated the city’s narrative over the last year.

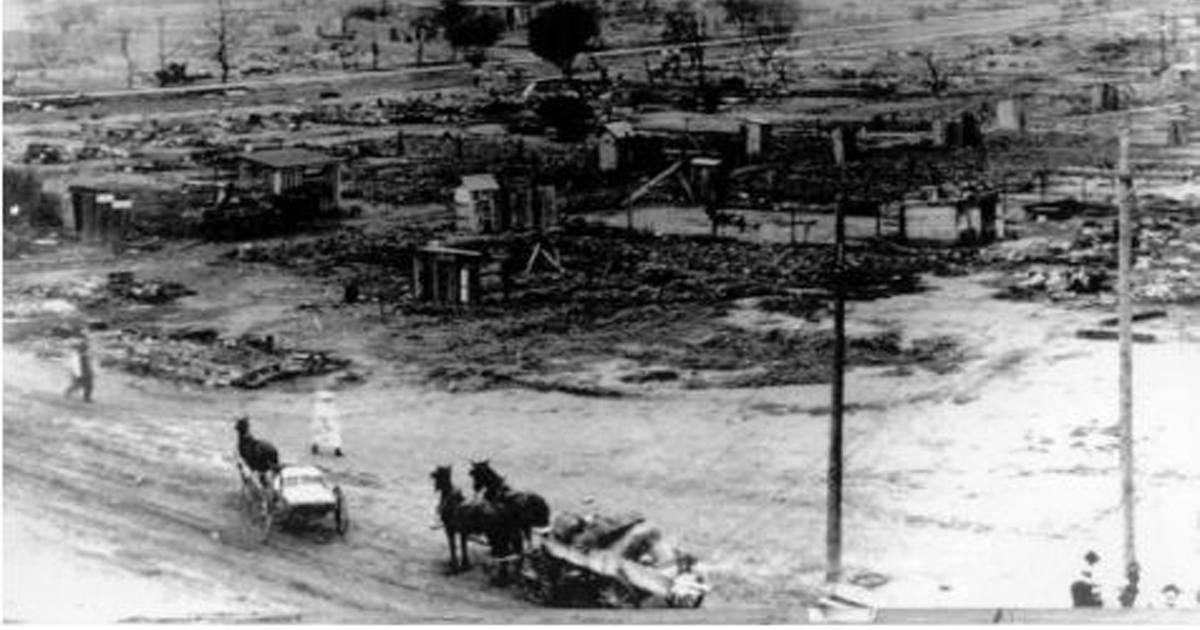

Until recently, the city hadn’t said much, and little was known in American textbooks about the city’s war against the Black Tulsan business community. One Hundred years on May 31st, 1921, white mobs descended upon the Greenwood Black business district, destroying over 30 blocks of Black-owned businesses, 1,200 homes, and killing over 300 Black residents.

Today, the 1921 Tulsa race massacre is almost ubiquitously acknowledged by national news outlets. A Harvard Business School professor even developed a case study now being examined by MBA students learning about local efforts of descendants seeking out reparations.

To date, none of the survivors or descendants of the massacre have been compensated by the city for the violence or destruction, estimated to be $200 million in damages in today’s dollars, of the thriving “Black Wall Street” on Greenwood avenue.

Instead, the story of the massacre has taken center stage, with last week’s centennial honoring the history of that tragic day and dedication ceremonies preceding the opening of the Greenwood Rising history museum, a near $20 million project not done by a Black contractor.

Locally, the sentiments on the investment into a multi-million dollar tourism project, in lieu of reparations to compensate for the loss of wealth Black residents would have achieved had their businesses been allowed to thrive, invited protests and discontent at many of the public gatherings held last week.

The discrepancy lends itself to the conditions of Black Tulsan life today. Black Tulsans earn an average of $33,000 annually, compared to roughly $55,000 earned by their white counterparts.

Despite Black people representing 10 percent of the city’s population, only 1.25 percent of the local-area businesses are Black-owned. . Barriers to direct access to capital, investment and lending continue to stunt business growth and ownership in a city that 100 years ago was a leading force of the American dream for Black people.

The Newcomers

Tulsa’s Black Wall Street story has no doubt attracted the attention of outsiders seeking to rebuild what the massacre destroyed.

There’s Atlanta rapper Killer Mike who launched Greenwood bank with investors last year. New Black Wall Street, a Los Angeles-based fintech company, announced its app aimed at teaching financial literacy and cryptocurrency to Black consumers.

And then there are those who’ve set up shop to build directly within the city’s limits.

Randolph “Randy” Wiggins relocated to Tulsa just eight months ago as a venture partner at Atento, abandoning his tenure in Silicon Valley to launch and lead Build in Tulsa, an initiative aimed to add a bit of padding to the chasms between the city and its local Black community with a curated list of board members, financial backers and local recruits.

Wiggins walks and talks like what some imagine Black businessmen in Tulsa to have been: studied, astute, charismatic, focused and in tune with the realities of the disparity, adding an effort to use his Silicon Valley knowledge to shape Build in Tulsa (BIT), an ecosystem mandate to bring capital, mentoring, networking and resources to the city’s Black entrepreneurs.

“Our initiative is titled ‘First in Line,’ This means first in line for resources, connections, financial support, everything that an entrepreneur needs to be successful,” Wiggans explained to a crowd of over 150 guests during last week’s announcement of BIT during last week’s centennial anniversary celebration.

The Princeton University and UCLA law graduate has cultivated a list of backers and moneyed institutions for BIT, including that of Princeton Innovation Center, several family foundations and board members like John W. Rogers, Jr., CEO and Chairman of Ariel Capital Management Investments, and a direct descendent of real estate entrepreneur J.B Stratford whose 54-suite hotel was burned down during the massacre.

The BIT team boasts a roster of local Black Tulsans who shared stories of their kinship to the city, the high schools they attended, and excitement for their work to bring BIT forward.

“This is not about people coming from outside. You had native Tulsans teaming up with African Americans from across the country and coming together to build something great. And 100 years later, that is what we are looking to do again,” Wiggins told The Plug.

The Infrastructure

The Build in Tulsa model proposes a robust, multi-phase, 10-year, $200 million plan that roots itself in strategic partnerships, youth and entrepreneurship programming and scalable entrepreneurship support services.

The first phase of the initiative is a three-year commitment of hosting national accelerator programs targeting Black founders and operated by TechStars and Black-led firms like ActHouse and Lightship Foundation (formerly the Hillman Accelerator). Each accelerator brings with it capital investment opportunities to help funnel money into businesses it hopes will grow and sustain within the city.

“We’ll educate people here. We’ll attract people here, and work toward retaining people here as well,” Candice Matthews Brackeen, Executive Director of Lightship Foundation, told The Plug. “There are tons of mechanisms being deployed to grow this and now is the time.”

Lightship Foundation will run its accelerator program over the next three years in the city, hiring a local managing director and investing $250,000 into five companies per year over the length of their program.

Global startup creation platform ACT House, led by Dominick Ard’is, will run six-month accelerators for early idea creation for entrepreneurs, host monthly hackathons and serve as a landing pad for those who wish to come to Tulsa and start a company of their own.

“We’re finding balance amongst a harsh history. We wouldn’t be here without the awakenings of 2020,” Ard’is, a Florida native, told The Plug, adding the accelerator has already received 55 applicants and will host eight to 10 early-stage entrepreneurs this summer.

Thus far, BIT has raised almost $15 million within its first year of fundraising and plans to raise at least $85 million to carry out its two-phase development through 2026, which also includes graduating 30+ entrepreneurs from its partner accelerators, building a dedicated Black Tech headquarters, creating a $10 million seed fund to invest in Black founders and partnering with big tech companies to bring Black remote employee cohorts to Tulsa.

Mounting a Legacy

The Build in Tulsa initiative joins the ranks of local efforts and initiatives aimed to center Black builders across the city and champion innovation and business growth for Black entrepreneurs and aspiring tech workers.

Led by Tyrance Billingsley, II, Black Tech Street recently announced its partnership with social impact innovation agency SecondMuse to build a hub to support local Black founders, attract investment capital to the city, and support tech job training.

Urban Coders Guild, launched in 2017 by former IT director Mikeal Vaughn, trains middle and high school students from historically underserved and underrepresented communities to code. After returning from Japan, Vaughn launched the nonprofit organization with plans to create an information ecosystem where students can learn critical thinking skills, the technical skills of the future, and earn opportunities to apprentice.

Future Forward

The energy and momentum of Black ecosystem leadership in Tulsa mirrors that of ecosystem building efforts for Black founders and technologists across the country, each one working to mitigate the less than one percent of venture capital dollars invested in Black founders each year.

Whether these initiatives and models turn the tide in total for centuries of discrimination and lack of resources for Black businesses remains determined. What matters most is that they exist and represent both a changing narrative and a repositioning of opportunity driving access for those who have been historically locked out of the tools necessary to create thriving businesses.

Ioneeyau Casey, who has lived in the city since the age of seven, joined the BIT team in January to lead administrative efforts.

“We’re creating something I wish I had when I was in high school that students and entrepreneurs will have a reason to stay in Tulsa,” she said to a crowd during the launch event for BIT.

“I fell back in love with this city. There is fertile ground here.”