Barry Givens built a robot that was the life of the party. The Atlanta-based entrepreneur launched the artificially intelligent bartender Monsieur in 2013 at Techcrunch Disrupt Battlefield following a successful Kickstarter campaign which helped to bring the product to life.

Monsieur’s technology poured any combination of 300 cocktails and was a hit sold within bars for just under $4,000 per device. The robotic bartender became an instant fan favorite. But when sales slowed, Givens was forced to license the technology or sell his intellectual property.

Despite having raised over $4 million to grow the company, Monsieur was short-lived.

There comes a point where hustle is not enough and this is a really hard decision for great founders to come to terms with, Givens told The PLUG. We also had to deal with the realization that the amount of capital needed to take advantage of this opportunity was going to be damn near impossible to attain based on the valuation of the company and the fundraising environment we were in.

Sure, companies like Givens shut down every day. According to CB Insights, 97 percent of seed or crowdfunded hardware companies eventually die. Statistically, most startups don’t last five years before closing up shop. But for Black founders who already find it difficult to raise the capital they need for growth, fighting for survival sometimes no longer makes sense.

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Business Employment Dynamics shows roughly 80 percent of new businesses failed within the first year between 2005-2017. Even with the rise of Black-owned businesses across the United States, Black founders still face uphill challenges with launching, scaling, and growing beyond the five-year threshold.

We profiled Aniyia Williams in 2018 about the challenges of being a Black woman founder and CEO in the hardware space. Back in 2014, Williams had the idea for Tinsel, a hardware company that created headphones that doubled as fashionable jewelry for women. Prior to the convenience of AirPods and other wireless headphones, many cell phone users still had to spend a little time untangling the cords of their beloved earbuds before taking a call or listening to their favorite song. She created the world’s first audio necklace known as The Dipper and owned the patent to match. In an open letter on Medium, Williams documented her company’s most dire challenges and announced that Tinsel would stop shipping product to customers as of March 2019.

Honestly, it was a long process for me. I went through my own five stages of grief, Williams admits, who initially started to slow down her company’s operations as early as the end of 2017 and cash flow took a hit. Hardware is expensive.

In the company’s lifetime, Williams raised a total of $500,000 with her co-founder Monia Santinello, which she says paid for product development and manufacturing expenses.

As production started to slow down, it was important for her to pay the team and the vendors what they were owed. Shortly after, she had conversations with other stakeholders in stages. A failure is ALWAYS an option, Williams said. It’s by no means the goal, but we have to be willing to take an “L” if we want to create space for new wins. Little did she know that her experience with Tinsel would usher in an opportunity for her to help other Black and Brown Founders start companies without relying on venture capital funding.

When I started Tinsel, I didn’t know if creating necklace headphones was even possible. Part of me wondered if that was why no one else had done it yet, Williams wrote in a personal Medium post published earlier this year, announcing Tinsel would be shutting down its operations. But you see, I really like challenges, especially when everyone else says it’s too hard. And I decided to sink my teeth into this one.

Today, Williams serves as co-founder and executive director of Black & Brown Founders, a community that provides Black and Latinx entrepreneurs with the resources they need to launch and scale their companies.

It was my experience both raising capital for Tinsel and feeling like the venture capital model had a gaping hole in it, Williams said. I decided that I didn’t have years to wait for the people on the other side of the table to get more diverse.

Black & Brown Founders’ first event was the final project from her entrepreneurship residency with Code2040, with hopes to create a space to share useful information about how founders can launch their businesses even if they never see a dollar of investor money.

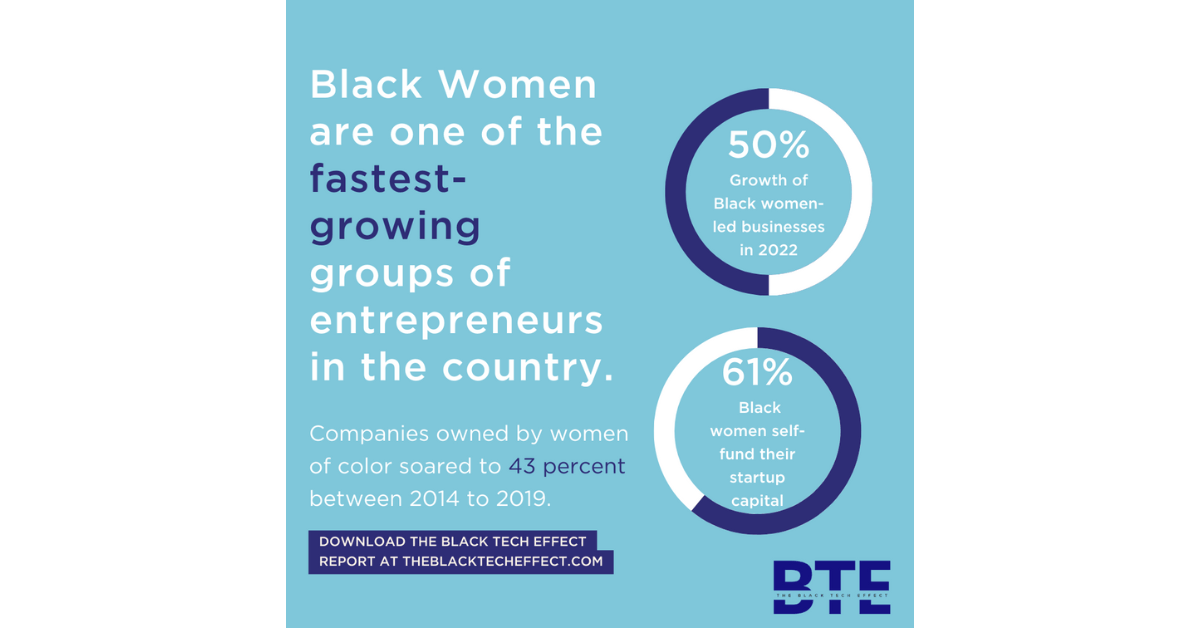

For Jenifer Daniels, she realized it was time to sunset Colorstock, one of the first startups offering a solution to the lack of Black and brown individuals in stock photos after she exhausted a few avenues of alternative funding. A report by The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City found that 50 percent of Black women founders use personal or family savings to fund their business. This held true for Daniels. Since the company’s conception, Daniels had financed Colorstock by bootstrapping on her family’s time and dime.

Colorstock broke even the first three months of operation and I even earned my investment back in one year, she recalls. However, once sales started to stagnate and competitors showed up, I had to make a decision around additional personal funding (which would have meant tapping into her 401k) or seeking venture capital. When venture capital didn’t make sense, she entertained the idea of being acquired.

And when that option didn’t pan out, she made the decision to sunset the company in March 2018.

In closing down her company, Daniels realized that this was only an opportunity to make her next business venture defensible. To quote Dorie Clark, ‘it isn’t a failure, it’s data,’ Daniels said. No one person or company can copy my business model because I am solving a unique problem in a way that only I know how to do. That means I will work harder to identify my next ‘leap’ and it will be worth it because I’ve already had all the game run on me.

In her post-founder chapter, Daniels is doing work that truly excites her and to date, she has paid it forward by investing in urban art, parks, and placemaking initiatives in the city of Detroit.

As my focus has shifted to returning to my hometown and investing in Detroit’s people, places, and purpose, I’ve learned that a small dollar investment can be a catalyst for change and that my brand of leadership is servant leadership, she said.

Her new role as the director of the Wayne State Innovation Studio allows her to invest in people that look like her or had similar experiences to her own growing up in Detroit. Wayne State also happens to be her alma mater, which makes her even more proud to work on solving today’s problems with a social innovation lens. I see my role as catalyst, connector, and champion for Detroit’s brightest and best, she said, and I can’t wait to set this solid foundation as we relaunch the studio in the fall.

Givens biggest takeaways from his experience: It’s too expensive to raise money and not every check is worth chasing.

Don’t just chase the check — make sure the person writing it fills an experience gap on your team, he said. We spent five figures traveling around the country chasing seven figures, and some of that money could have been saved if we knew exactly who we were talking to. Givens cautions founders not to make any travel arrangements without speaking to someone who actually has authority to and the history of writing checks. Everyone else is a phone call, video conference, or coffee meeting.

In the newest chapter of his entrepreneurship journey, Givens has teamed up with fellow Atlanta-based founders Jewel Burks Solomon and Justin Dawkins to launch Collab, a company with the sole purpose of increasing opportunities for Black entrepreneurs to build wealth through entrepreneurship.

They’re housed in Atlanta because of the strong presence of Black entrepreneurs and have plans to expand by collaborating with the organizations and people in other cities.

Our goal is to bring all facets of the Black community (founders, athletes, entertainers, creatives) together in order to build, support, and grow wealth-generating business opportunities in our community, Givens said. To do this, we focus on filling the gaps that are hindering Black entrepreneurs from reaching the next level: technical gaps, talent gaps, capital gaps, relationship gaps, just to name a few.