Everyone is middle class until they lose their job, says Sheena Allen, CEO of CapWay, on a late Friday afternoon while she works from her Atlanta office. Her observation falls in line with that of researchers who project that as the pandemic drastically hollows out America’s middle earners via more job cuts, poverty rates could reach levels on par with those of the Great Depression.

With unemployment stretching across the country and affecting jobs in every sector, Allen and her team at CapWay have been quietly building a digital literacy and banking solution befitting the era of digital-first payments and transactions for the 55 million Americans, 20 percent of whom are Black minorities, left out of traditional banking systems. “Most people in my [community] cashed their checks at the grocery store and used payday lenders and other often predatory financial providers, Allen recalled in an interview with Inc. last year. “We’ve lived the problem, so let’s be the solution.”

Where other tech startups have braced for long-term hits to their core businesses, CapWay is aligned with post-pandemic predictions of mobile banking as usage surges and more Americans get accustomed to managing money from their smartphones. Allen initially planned to launch the CapWay debit card early this spring but shares that the card will more than likely reach customers late summer. As it stands, there are no public details as to how the debit card will operate or what fees will be associated with holding an account with CapWay.

First of Her Kind

Allen is one of the first Black women to own an online-only bank in the United States. There are presently just 21 remaining Black-owned and operated banks in the country, that is very much still tied to brick-and-mortar branches. She’s also barely in her 30s, making the endeavor impressive but not without its challenges. The debit card delay came as a hurdle when CapWay came up against barriers with its former banking partners. Instead of battling it out in the second quarter with the novel coronavirus for space in the news cycle, CapWay got out of their contract and built a new model for working directly with their banking vendors instead of with a third party.

We wanted direct relations with people who ran the engine behind the bank. I wanted [the ability] to go directly to the vendors running processing or [who] know your customer, explains Allen, citing that the delay was a contract problem, not an execution problem. Allen hasn’t shared what fees will look like for the CapWay debit card.

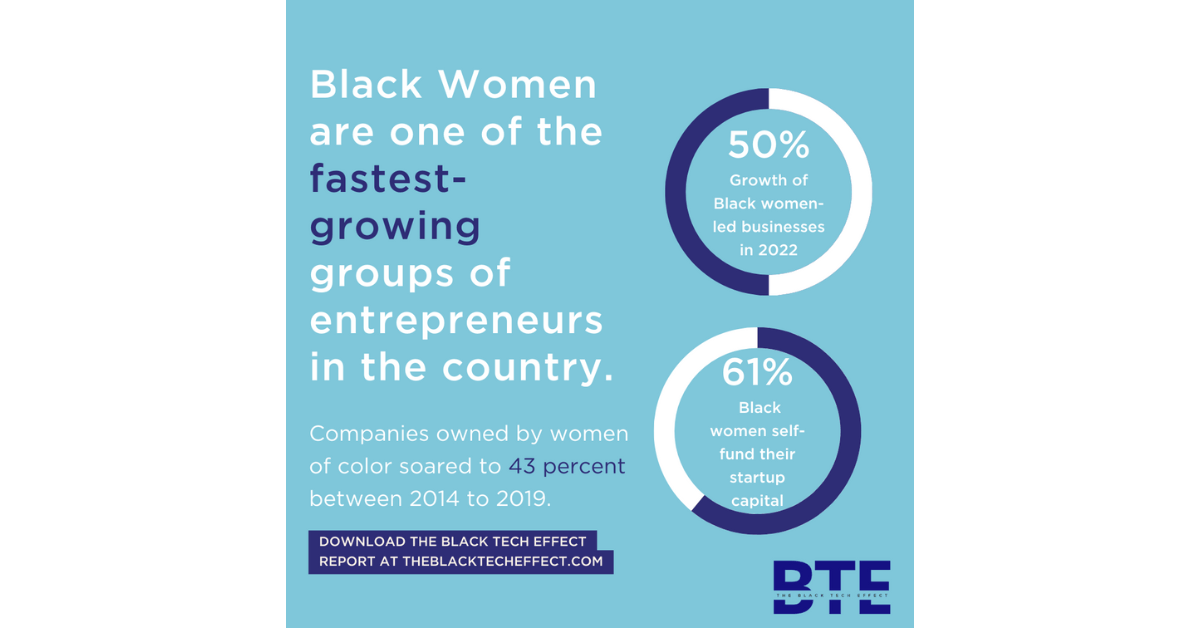

Popular category competitors like Venmo and CashApp don’t charge fees for transferring or receiving money through their debit cards. ATM fees are $2.50 and $2.00 respectively. With just under $1 million in the bank ‚Äî most fintech companies launch with $1.5 to $2.5 million, Allen says, pointing out the glaring disparities of raising capital as a Black woman in tech‚ CapWay will raise a bridge round to get through launch.

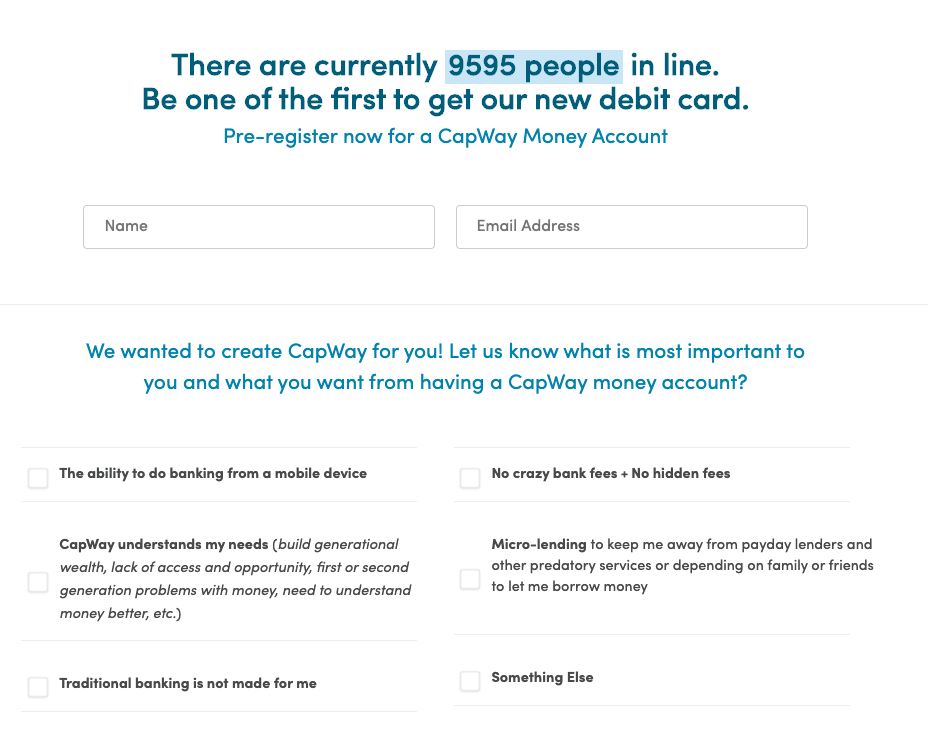

For now, CapWay is quickly building its funnel for potential customers. According to its website, there are over 9,500 users waiting to get their hands on the forthcoming debit card.

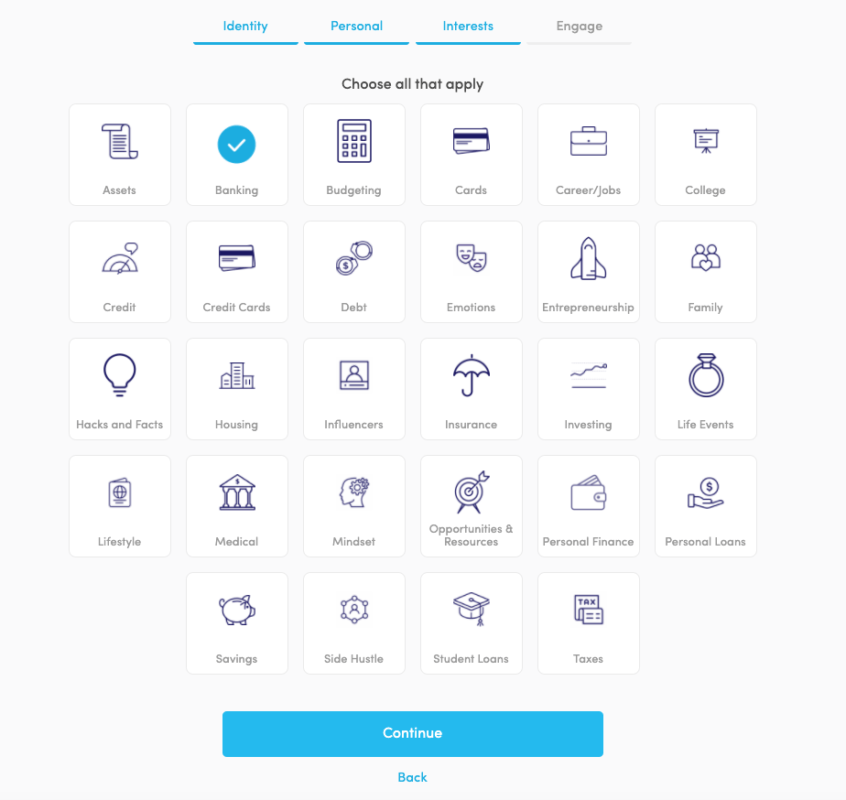

The onboarding process from its website includes a series of questions to gather information on a user’s banking needs, asking for details about career support and lifestyle interests as well as prior experiences with banking.

Inadequacies of The Alternative Banking System

Pawnshops, check cashing spots, and other forms of quick access to small amounts of cash have long been staples in the alternative banking economy, particularly in poorer neighborhoods. Access to these products has come at a hefty price.

Some states don’t cap these interest rates, which can be as high as 350%. Another challenge to these forms of money access is that they leave customers vulnerable and unprotected by traditional banking benefits like FDIC insurance, which provides protection up to $125,000. But where banks leave off, the new world of mobile banking provides a temporary lifeline. Square-owned Cash App incidentally saw a boost in usage among the underbanked as people making less than $50,000 began using the app.

But short-term solutions are by no means what Allen is attempting to create long-term savings and investment products help grow wealth. And she plans to offer microloan options in 20201, sans predatory fees, to keep users out of pawnshops and check-cashing stores.

With the anticipated late-summer launch for CapWay’s debit card, it will be interesting to see whether or not increased access to financial literacy will become a priority for consumers who face delayed stimulus payments, unemployment uncertainty, and trying to survive one of the worst economic downturns we’ve seen since the 2008 Great Recession.

*Editor’s note: In an earlier version of this article, we wrote that Allen plans to launch microloans this year. It has been updated to reflect microloans launching in 2021. We regret the error.