Key points

- The amount of “rug pull” scams in crypto has surged in the last year.

- Telling the difference between a rug pull and a bad investment is not easy for authorities.

- Authorities will favor investigating the easiest cases with the highest visibility according to a lawyer.

Famous Last Words

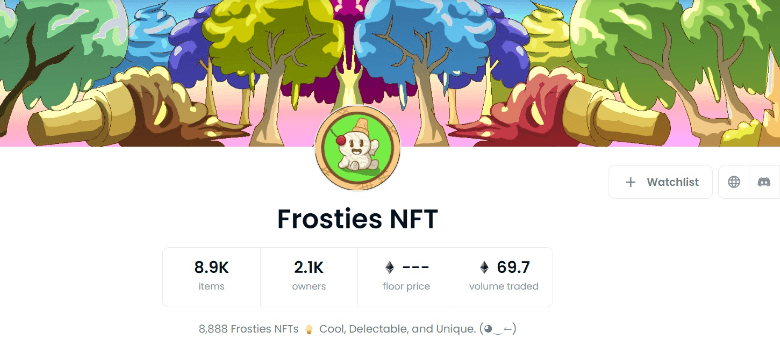

This was one of the final messages by Ethan Nguyen, the co-founder of an NFT project called “Frosties”, to the admin of the project’s Discord server just before he disappeared with $1.1 million of investor money. “I know this is shocking, but this project is coming to an end. I never intended to keep the project going, and I don’t have a plan for anything in the future.”

Ethan Nguyen and his co-founder – Andre Llacuna – were later arrested by authorities and subsequently charged with wire fraud and money laundering. Both await sentencing.

The popular Frosties project promised a video game, valuable NFTs and other rewards. But that never came to fruition and the project was ‘rug pulled,’ a colloquialism in the NFT space for a scam where developers suddenly disappear with investor money. Rug pulls are common in the NFT space, but authorities investigating them are not.

“Authorities will look at a number of things. Can you recover assets for the victims? Is your effort going to get you people you can physically punish, or are they somewhere you can’t reach them?” Martin Auerbach, Counsel at the law firm Witherworldwide with expertise in securities, cybersecurity and wire fraud, told The Plug.

Nguyen’s admission that Frosties was a scam made it easy for authorities to make the decision to go after him and Llacuna, according to Auerbach. “The admission of intent is pivotal, you had a person saying this was fraud, this was a scam. That hard to prove element was made easy.” But, unlike James Bond’s talkative villains, crypto thieves don’t lay out their plans before executing a scam, which can make it hard to police the crypto space. For example, the actual jurisdiction of crypto scammers can be difficult to ascertain without a big investment of investigative work. The huge effort involved in bringing bad actors to justice is partly why scams – and more recently rug pulls -are an accepted part of the space. It might also explain some of the confidence displayed by scammers (authorities say Nguyen and Llacuna were already planning their next scam before their arrest) and the huge rise in rug pulls in the last year.

Crypto scams are changing

A report by blockchain data company Chainalysis found that the average financial scam was active for just 70 days in 2021, down from 192 in 2020. Rug pulls in particular saw a huge growth last year, accounting for 37 percent of all cryptocurrency scam revenue in 2021, versus just one percent in 2020, the report found.

It is not always clear legally what is and isn’t a scam or a rug pull. In February, the BBC pulled a documentary from airing at the last minute about crypto-investor Hanad Hassan, who had made millions from his investments.

Hassan founded a charity-focussed token called Orfano, but six months after launching the project, it was closed down. Out-of-pocket investors on Reddit and Twitter accused the founder of running a rug pull. Orfano may well have been a scam, but in contrast to the Frosties project, Hassan was open about his identity. Founders of other large rug pulls in 2021, like the Squid token, have remained entirely anonymous. Cases like this show the difficulty of drawing a line between a rug pull and an investment that has simply gone wrong.

“Usually you’re looking for circumstantial evidence of intent. A legitimate person doesn’t try to hide who they are and they don’t run away with the money. They stand up and say here’s what I tried to do. If they take the money and run, that’s a good indication that someone is a scammer,” Auerbach said.

Recently another token, Chedda, saw its price suddenly drop 50 percent when a developer removed $1.17 million from the project, according to the Web3 Is Going Great blog. The team behind Chedda claimed a rogue third party developer drained the token of its value without their knowledge. Despite this, the project is ongoing and the main Twitter account is still promoting the token.

The Plug asked the US Department of Homeland Security Investigations, which investigated the founders of the Frosties project, what criteria needs to be reached before it investigates a potential rug pull. A spokesperson said that the “HSI takes any allegation of fraud very seriously, but the specifics that lead to an investigation vary greatly in each situation, so it would not be responsible to speculate on the viability of a potential lead without comprehensive analysis.”

Unfortunately, the crypto space is bloated with bad actors

Chainalysis’ research on the rise of NFT scams can be seen on the ground, too. The Next Web (not related to The Plug) reported last month that verified Twitter accounts – including those of politicians and sports stars – were being hijacked. The compromised accounts were tweeting out malicious links in an attempt to trick people out of their Ether (a cryptocurrency) or NFTs. It’s not just the crypto-ignorant being targeted either, veterans with healthy wallets are frequently targeted too.

Irish NFT artist Brian McCarthy explained to The Plug that he had almost lost all of his Ether to a sophisticated scammer posing as a gallery giving away free NFTs, which he figured out at the last minute. McCarthy would have lost thousands of pounds from his NFT sales in a moment had the scammer been successful. “Even savvy people like myself can fall victim to a scam, it’s important to highlight this” McCarthy told The Plug. Recent court cases like Armijo v. Ozone Networks, Inc show how successful wiley thieves can be with phishing attacks. In another case, a Bored Ape Yacht Club owner lost their NFT to a phishing attack, which was worth 99Eth ($281,153 at the time of writing).

The NFT and crypto space may well be inundated with bad actors looking to take advantage of people, but the IRS and Department of Homeland Security Investigations charging Nguyen and Llacuna could be a turning point. The efforts by authorities to track down Nguyen and Llacuna show that it’s not easy for scammers to disappear into the internet ether and whatever sentences are handed down to the defendants may well deter others. “There are two kinds of deterrents: general and specific. Specific means ‘I’m going to get these bad guys and stop them from doing it again’. Whereas general detence sends a message. General deterrent cases are favored by authorities because their high visibility means they are more impactful”, Auerbach told The Plug.

-Janhoi

Janhoi is a UK based journalist who specializes in tech. He is a recovering founder and his name is pronounced jan-eye.

If you liked this entry, have questions, or have other things you’d like to see covered by The Plug, please let us know! Please email king@tpinsights.com.