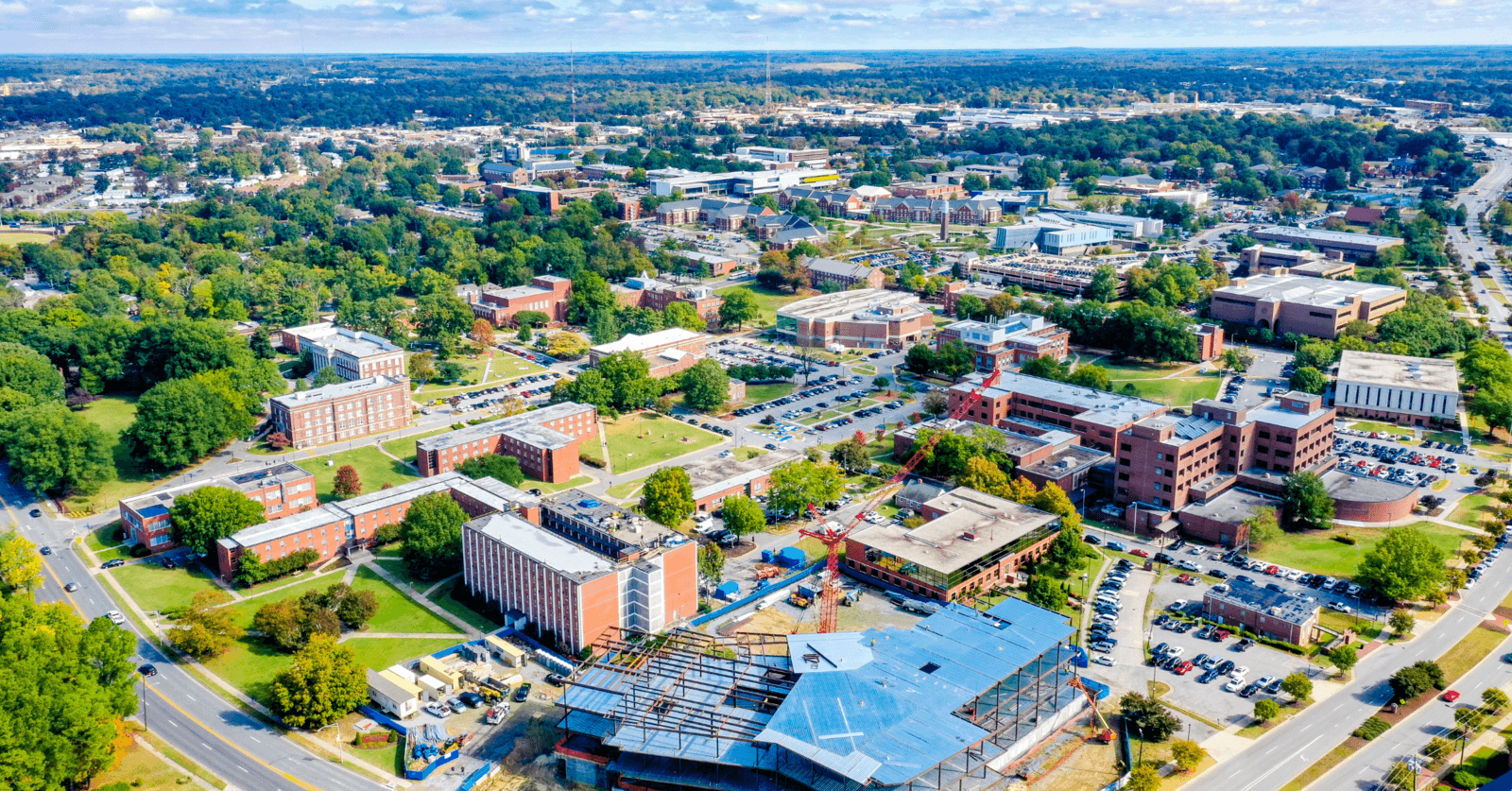

On a grassy expanse in New Orleans, under the shade of stately oak trees, sits Dillard University, Louisiana’s first Historically Black College and University.

But look deeper at that oasis and you will see an engine of upward mobility. Among nearly 600 selective private colleges, The New York Times has ranked Dillard as fifth in its overall mobility index, the likelihood that a student from a low-income family moved up two or more income quintiles as an adult.

“It’s the ethos of the institution to be able to say, ‘How do we create an environment for students with [large financial] needs so that they can be successful?’” Walter Kimbrough, the President of Dillard, told The Plug.

Dillard’s neighbor, Xavier University, Tuskegee University and Bethune-Cookman University were also ranked highly by the New York Times.

Among nearly 400 selective public schools in the Times’ mobility index, HBCUs make up almost half of the top 20: Grambling State University, Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge, Elizabeth City State University, Jackson State University, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and Southern University in New Orleans.

Overall, a college education frequently improves future financial outlook. The median earnings for people with only a bachelor’s degree are nearly $25,000 higher than those with only a high school diploma, according to a 2019 study by CollegeBoard. In June, people with only a high school degree were twice as likely to be unemployed than those with a bachelor’s degree or higher, 7 percent to 3.5 percent respectively, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

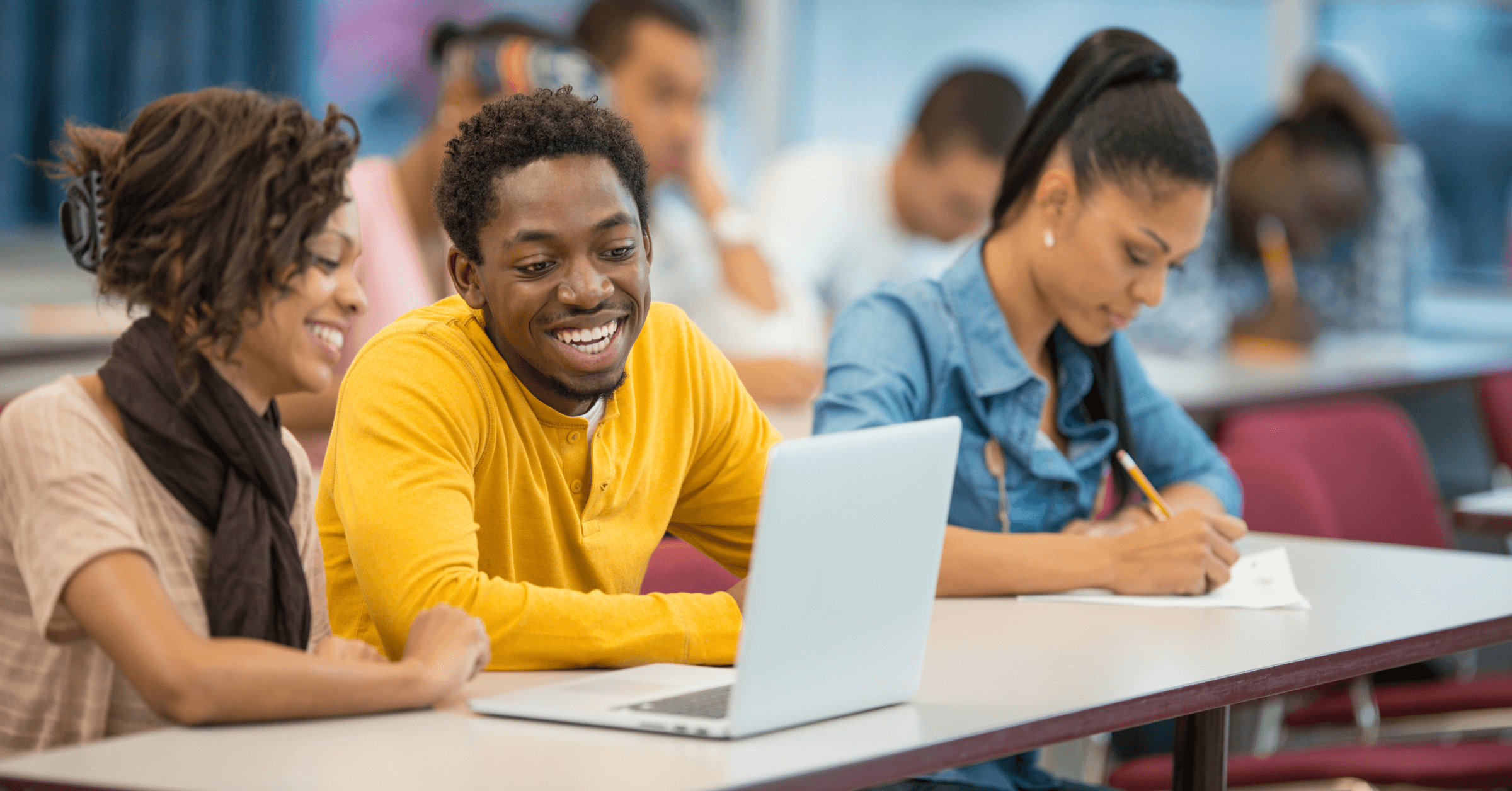

Among college graduates, HBCU students are more likely to reach rungs of the economic ladder that are higher than their families. A 2018 study found that 9.4 percent of students at non-minority serving institutions who came from families in the bottom two income quintiles were able to move to the top two as adults. That share more than doubles for HBCU students, at 19.3 percent.

Kimbrough said these higher economic mobility rates are because HBCUs provide more support than just telling students to attend class, which leads to better retention. On Dillard’s campus, that support is wide ranging.

“People buying a meal here and there because you know this person hasn’t eaten, or giving somebody a plane ticket to fly for an interview for graduate school. Or helping someone get home or pay a bill or watch their child when they need to go,” Kimbrough explained.

Another reason these upward mobility rates are higher is because HBCUs typically enroll a larger amount of low-income students. At Dillard, the median family income is $30,800, according to The New York Times. That means a larger share of the student body has the possibility of moving up the economic ladder after they graduate than at a school like Louisiana State University, where the median parent income is $108,800. It ranks 224th among selective public schools in the Times’ overall mobility index.

But accepting more low-income students is a double-edged sword. It can also negatively impact overall graduation rates, a traditional way of measuring a school’s success that is used as a key metric in rankings by US News and World Report, and in some cases, the amount of state funding a school receives.

Research shows low-income students are a lot less likely to get their bachelor’s degree in six years. In 2019, students from the highest income quartile were nearly five times more likely to graduate than those in the lowest income quartile, 62 percent vs 13 percent respectively, according to a recent report from the Pell Institute and the University of Pennsylvania.

Dillard’s six-year graduation rate is 51.7 percent, while the national average is around 62 percent and only about 40 percent for Black students. When students don’t finish at Dillard, it is normally because of finances and the host of challenges that come with it, according to Kimbrough.

Many states are adopting performance-based funding models for public higher education, tying state resources to metrics like graduation rates. One researcher found that funding to Tennessee’s only HBCU dropped on average by 0.23 percent in the first five years of performance funding, whereas for the other state universities it rose on average by 1.49 percent.

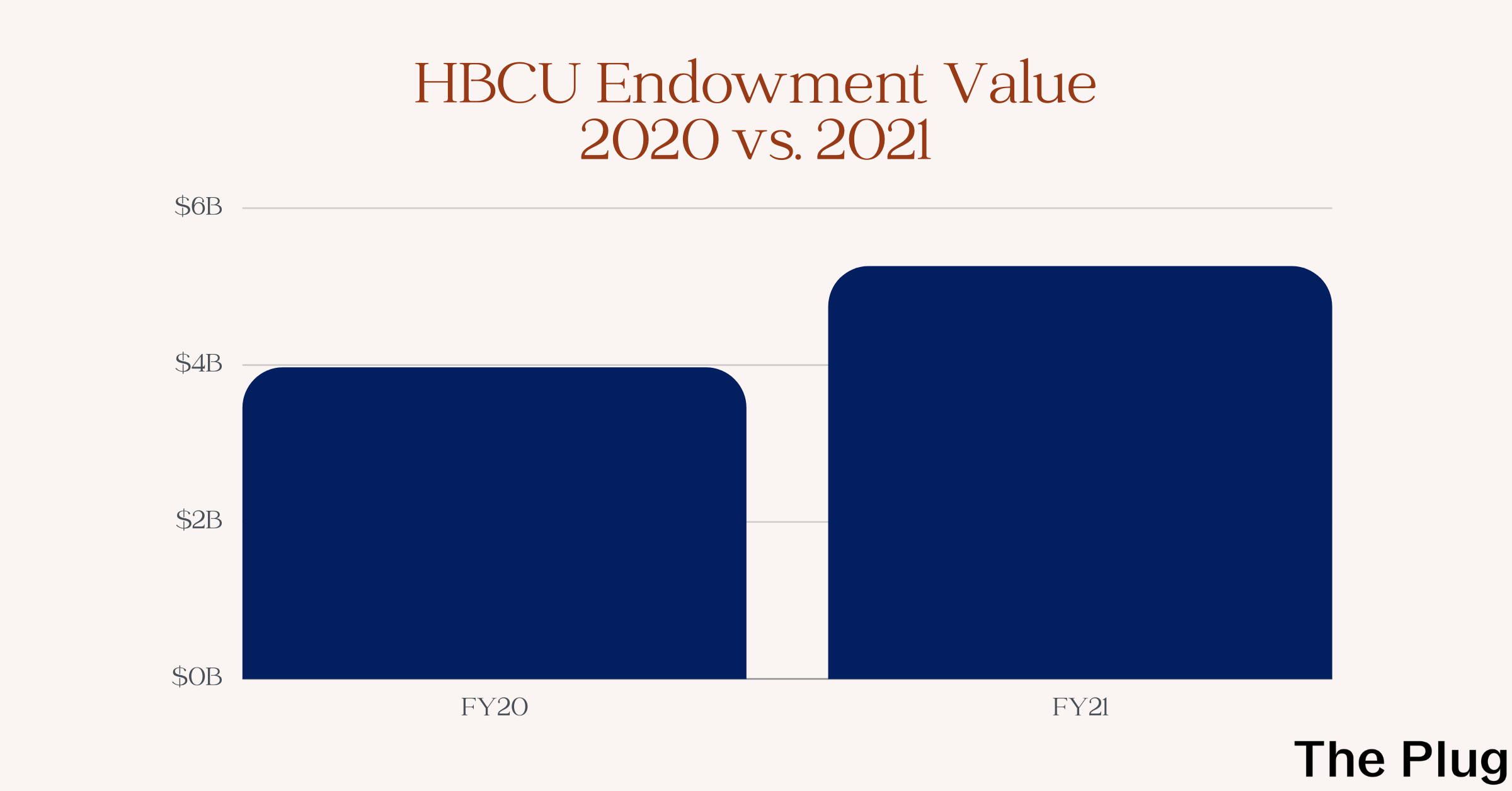

But HBCUs are already under-resourced institutions playing an outsized role in educating Black students and improving their economic situations as adults. For example, Dillard’s total endowment is only $105 million, which is roughly equivalent to just one of the hundreds of millions in donations Harvard received in 2019.

But with all these challenges, going above and beyond for students and helping retain them is integral to HBCUs. “I don’t think [people] understand the complexity of the population that we educate,” Kimbrough said. “You have under-resourced institutions educating an under-resourced population. That’s tough.”