Interested in getting HBCU stories straight to your inbox? SIGN UP for our executive HBCU newsletter to make sure you get exclusive videos, news and analysis in your inbox every Wednesday morning.

KEY INSIGHTS

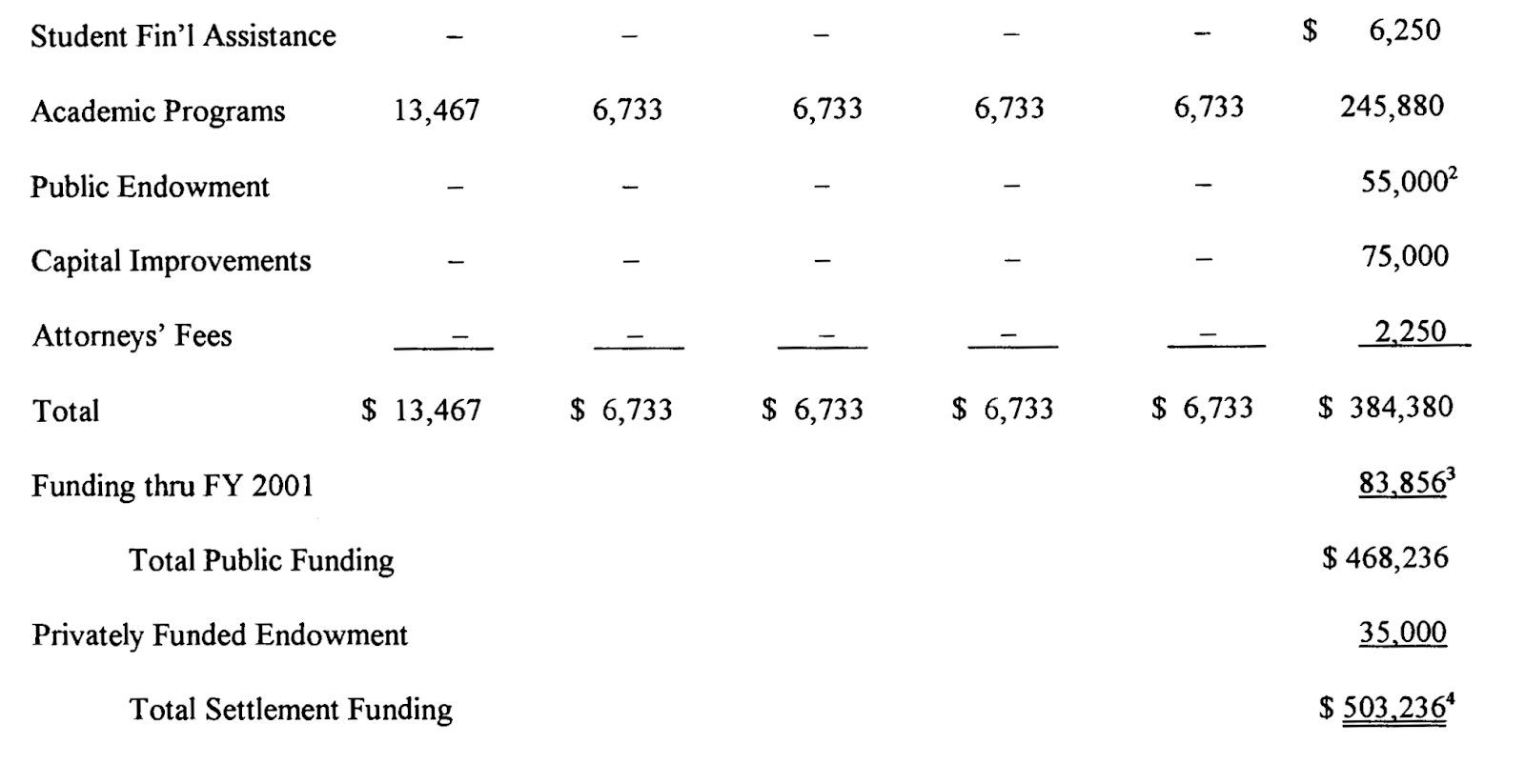

- In early 2001, Mississippi settled a class-action lawsuit that would have meant $500 million over two decades for the state’s public, four-year HBCUs.

- The funding ends as of June 30 this year.

- Critics say the schools have not gotten the full $500 million.

As states like Maryland and Tennessee begin to try to rectify decades of systematic underfunding of their public HBCUs, Mississippi is nearing the end of a 20-year settlement that aimed to do just that. Its example could provide lessons for other HBCUs.

In early 2001, the State of Mississippi settled a class-action lawsuit first filed in 1975, eventually reaching the Supreme Court, which alleged the state was discriminating against its public HBCUs.

“Our argument from the beginning is that Mississippi operated a dual system of higher education, one for Black students and one for white students,” Rep. Bennie Thompson, who represents Mississippi’s 2nd District in Congress and was a lead plaintiff in the suit, told The Plug.

After 26 years of court battles, Rep. Thompson and other plaintiffs negotiated a settlement that, if all the funding commitments were met, would have meant $500 million over two decades for Alcorn State University, Mississippi Valley State University (MVSU) and Jackson State University (JSU).

After June 30 this year, the funding ends. Since FY 2002, Alcorn has received at least $83.6 million, MVSU has received at least $88.9 million and JSU has received at least $207.4 million from the settlement, according to a 2021 accountability report — a total of $380 million along with at least $67.6 million in endowment funds distributed across the three schools.

A settlement decades in the making

By 1975, Black Mississippians had had enough. Though Brown v. Board of Education had made segregation in classrooms illegal 21 years prior, it was still alive and well by de facto in Mississippi.

Rep. Thompson attended JSU in the early 1970s and later went to the University of Southern Mississippi, a predominately white institution (PWI).

“If you at that time wanted a first-class education, all things on the table, then you would go to the historically white school because those resources were there. The legislative appropriations were altogether different,” Rep. Thompson said.

“They offered scholarship opportunities for students rather than loans. The extracurricular offerings, both on the academic and other side, were just glaring. Students had opportunities to travel. Students had opportunities to attend lecture series at no cost. Whereas Jackson State and other historically Black colleges struggled just to meet minimum standards,” he explained.

In January 1975, Thompson joined Jake Ayers, the lead plaintiff at the time, and other citizens to sue Mississippi, saying the state had violated the Fifth, Ninth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

The federal government eventually joined in support of Ayers, Thompson and the others, with the case reaching the Supreme Court in 1991. They ruled 8-1 that Mississippi had not done enough to dismantle the system that fostered segregation in public universities.

But it would take another decade for the state to finally reach an agreement, known as the Ayers Settlement, to provide at least some level of enhanced funding for the HBCUs.

Under the agreement, the state would provide $245.8 million to create and enhance academic programs at Alcorn, JSU and MVSU in disciplines ranging from computer science to nursing to civil engineering. They would also get up to $75 million to improve some campus facilities and fund new buildings.

The Ayers Settlement also established two endowments for the HBCUs, a $70 million publicly funded endowment and a $35 million privately funded endowment, although full disbursement of the funds was stipulated to only happen if at least 10 percent of each school’s student body was non-Black.

The state would also provide $6.25 million for scholarships to universities’ summer developmental education programs. However, the pool of money was available to all the public universities in the state, not just HBCUs.

Impact of the Ayers funding

When the settlement was finally agreed to, reports touted it as a $500 million investment that Mississippi was going to pour into the state’s HBCUs.

But Ivory Phillips, a 1963 graduate of JSU and Dean Emeritus of the JSU College of Education who also served as a consultant on the Ayers case, told The Plug that the schools have not seen nearly that amount.

“Jackson State, Alcorn and Valley as institutions, only got roughly $400 million,” Phillips said.

He pointed to the public and private endowments as well as the $2.5 million in attorney’s fees as money that did not go to the schools.

As of last September, only $1 million of the $35 million private endowment has been raised, according to the accountability report. Phillips also said that the money in the $70 million public endowment did not go to the HBCUs, but rather was for the white students attending those schools.

For Alcorn, the Ayers funding has gone to expanding teacher education programs, enhancing library and academic technology, building a fine arts facility on one of its campuses, renovating an existing building and creating a master’s in biotechnology.

For MVSU, the funding has gone to its STEM programs, scholarships, enhancing the library, landscaping and drainage around the campus, and a new science and technology building.

The funding has allowed JSU to open an engineering school, establish a master’s degree in public health and communicative disorders as well as a doctorate of social work, urban and regional planning and business, among other things.

In FY 2021, Ayers funding accounted for 3.9, 8.4 and 5.2 percent of Alcorn’s, MVSU’s and JSU’s total funding sources respectively, according to an analysis by The Plug of the school budgets. While that may seem to some a small piece of the budget, moving money to cover gaps within universities is not simple due to restrictions that typically come with funding and how the money can be spent.

Lessons for other HBCUs

The $500 million total of the Ayers Settlement is similar to what Maryland HBCUs negotiated after a 15-year legal battle that Rep. Thompson said was styled after the Ayers case.

Bowie State University, Coppin State University, Morgan State University and the University of Maryland Eastern Shore will receive $577 million over the next decade under the settlement agreed to last April.

This week, the governor of Tennessee unveiled a budget that calls for allocating an extra $318 million to Tennessee State University after a report last year laid out how the state had underfunded the HBCU by up to $544 million.

But though some of the funding commitments laid out in the Ayers Settlement have been reached, according to the state’s reports, segregation and systemic underfunding still have compounding effects.

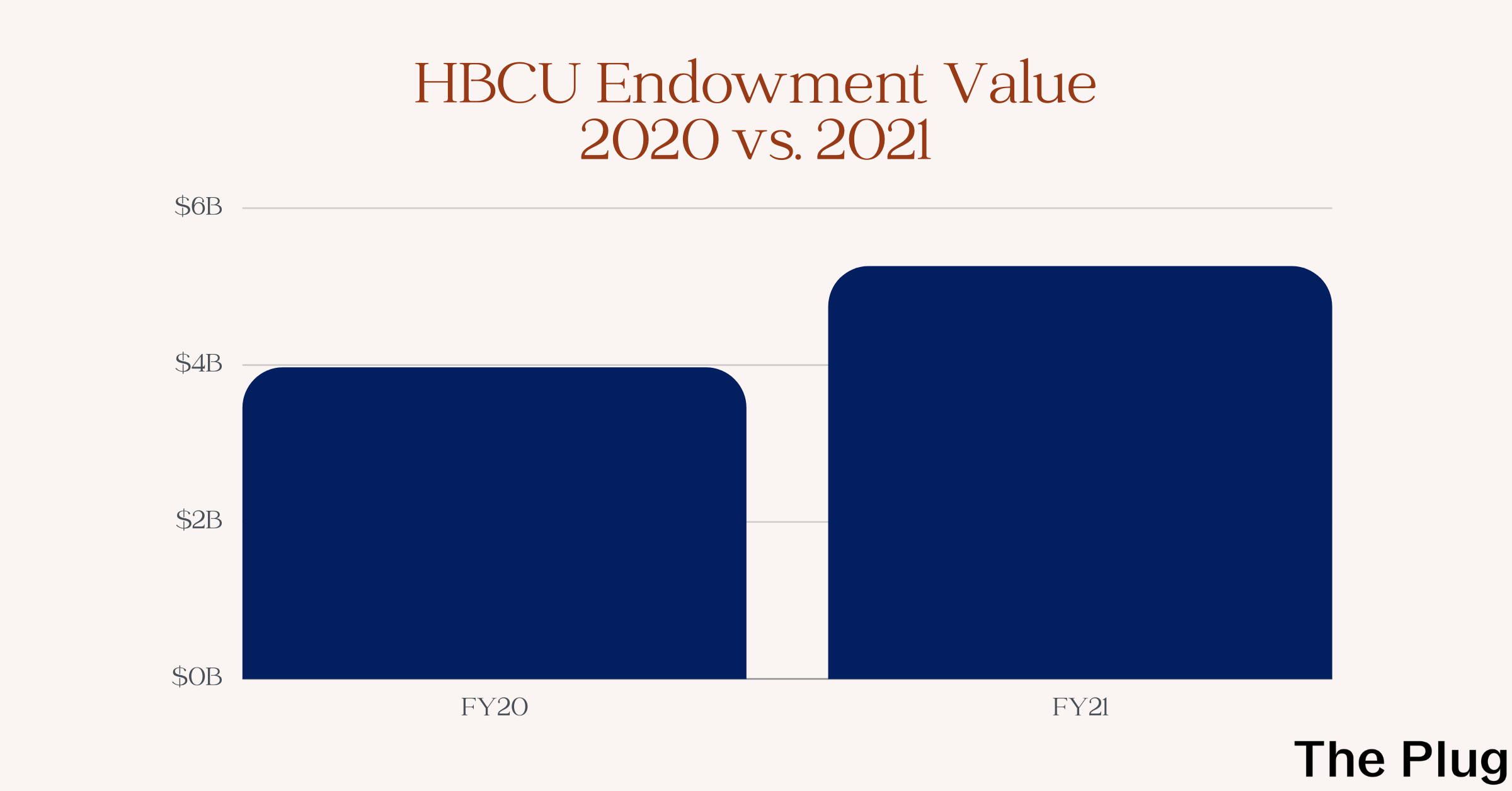

The value of Alcorn, MVSU and JSU’s endowments combined as of June 2020 was $69 million. It is just 10 percent of the endowment of the flagship PWI in the state, the University of Mississippi, which sits at a whopping $674 million, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

The Ayers Settlement was also a compromise. Phillips, who was eventually the head of the Faculty Senate at JSU, said one of the things they wanted but never received was salary equalization — that a professor teaching English 101 at JSU, for example, would get the same salary as a professor teaching the same course at the University of Mississippi.

But ultimately, settlements cannot completely solve governmental underfunding and neglect of HBCUs, Rep. Thompson said.

“White Mississippians don’t want Black Mississippians and their institutions to thrive,” he explained.

“No settlement is a panacea for equity.”