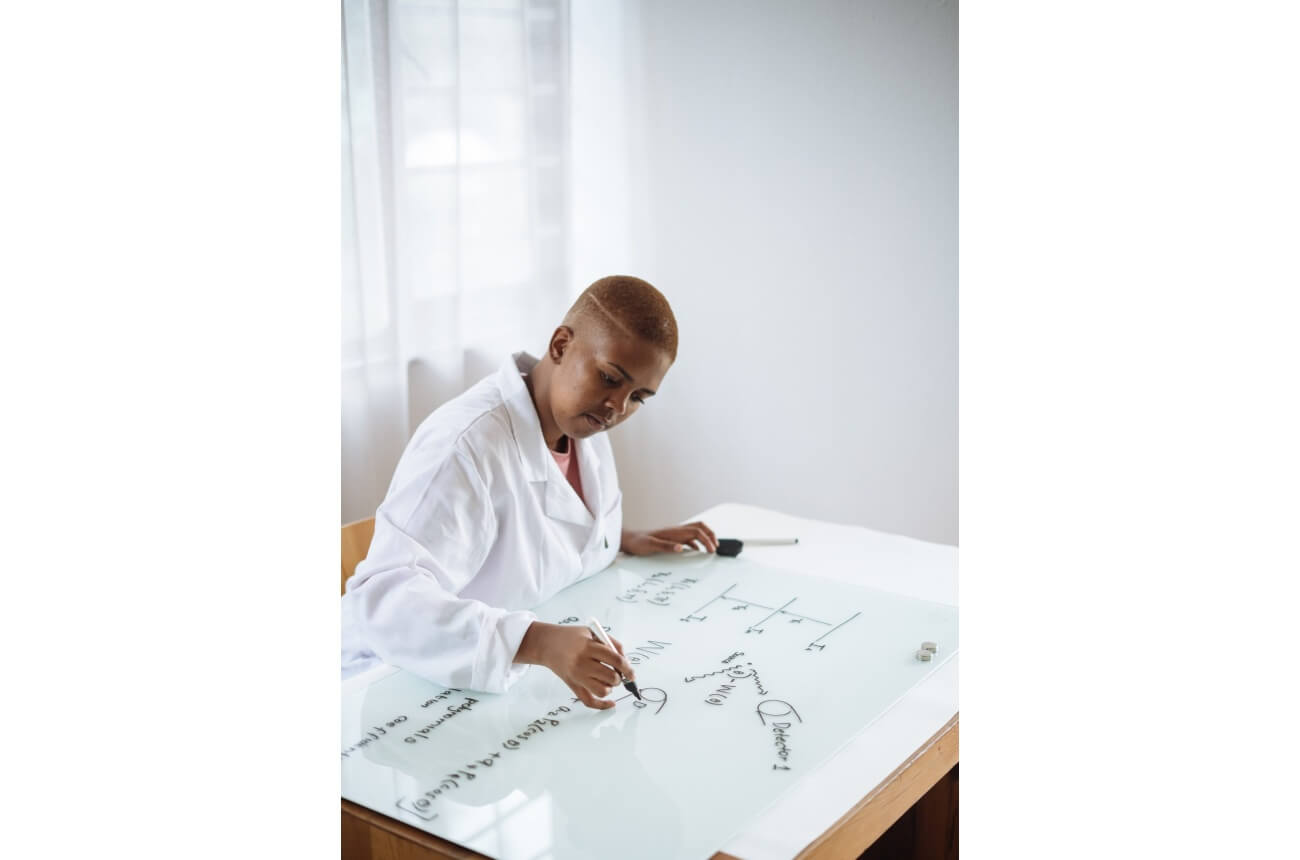

Though they are just three percent of all the nation’s four-year colleges, historically Black colleges and universities are small but mighty institutions that, in 2015, accounted for 15 percent of all bachelor’s degrees earned by Black students. Now, preliminary findings from a nearly million-dollar research project conducted by professors at Howard University, Claflin University and Jackson State University show Black students who go to an HBCU are more likely to graduate with a STEM degree than those who attend a non-HBCU.

“The preliminary results are exciting,” Omari H. Swinton, Chair and Director of Graduate Studies for the Department of Economics at Howard and one of the lead researchers on this project, told The Plug.

Almost 18 percent of Black STEM bachelor’s degrees are awarded from HBCUs and a third of all Black students who have gotten a doctorate degree earned their bachelor’s from an HBCU, according to the National Science Foundation (NSF).

This new research looked beyond what happens to a student once they graduate college, also analyzing student data starting when they were in high school all the way to their college graduation.

The NSF awarded Swinton, Nicholas Hill, who is the Dean of the School of Business at Claflin and a co-principal investigator, and their colleagues William Spriggs, Haydar Kurban and Maury Granger nearly a million dollars to conduct this research. The grants end in 2022.

Using a combination of data from the College Board, an educational organization that administers the SAT, and the National Student Clearinghouse, a nonprofit that collects data from high schools and colleges, the researchers were able to analyze the educational journeys of nearly 600,000 Black students who were college-bound between 2004 to 2007.

From the College Board data they were able to see students’ SAT scores, a questionnaire that included information on their parents’ education and income as well as their intended major and what schools the students sent their scores to. The researchers were then able to match that data to the National Student Clearinghouse data, which showed what colleges the students attended, their major at graduation and if they enrolled in graduate school.

“We’re able to see what their preferred major would be before they go to school,” Swinton said.

“We see what their major is in college once they graduate and so this allows us to see how well different university types do at converting students. If the push is to get more STEM majors, you would really want to see students who didn’t want to be in STEM fields graduating with STEM degrees, which means those universities are converting them.”

Their initial findings show that if you control for factors like SAT score, high school GPA, other pre-college conditions like family income and the characteristics of the college a student attends, Black students are 13 percent to 15 percent more likely to graduate from college in general if they attend an HBCU.

Of those who graduate, Black students who attend an HBCU are 5 percent to 10 percent more likely to get a STEM degree than those who do not go to an HBCU. Black students who were among the top scorers on the SAT were the exception — researchers did not see any positive impact on graduation rates or their likelihood of majoring in STEM if they attended an HBCU.

“The increase in the likelihood of [students] getting a STEM degree is important,” Swinton said.

“If you’re trying to diversify the STEM fields, Black students at HBCUs are more likely to get a STEM degree and they’re more likely to graduate in general and therefore, if that’s your goal, then you should encourage students to attend HBCUs because it will help improve diversity and other types of issues,” he continued.

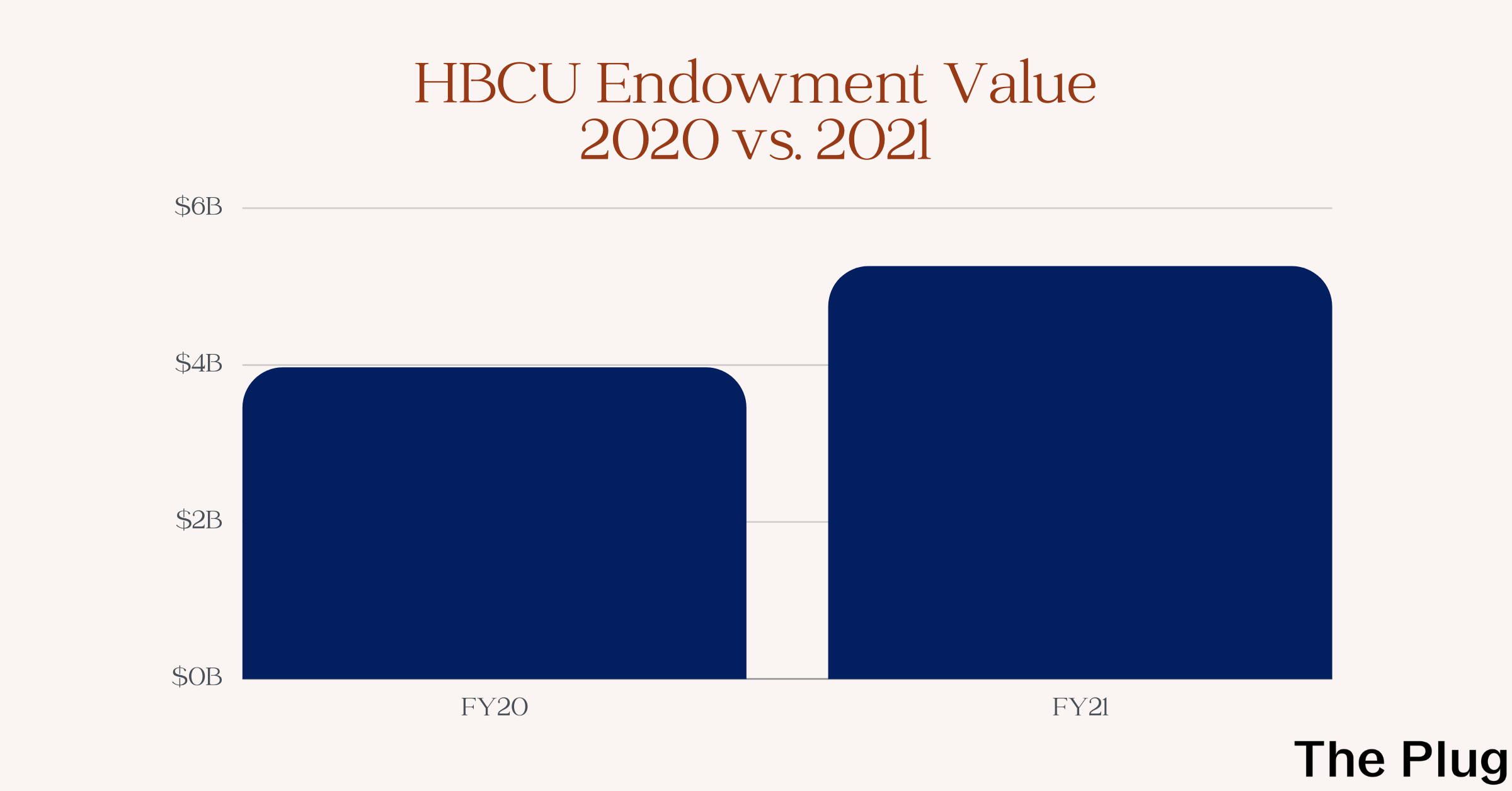

Nicholas Hill, Dean of the School of Business at Claflin, thinks the research could have a positive impact on HBCUs’ resources and that it quantifies something the researchers have already known.

“It provides an ample amount of support for us as administrators to advocate for more funding and for the spotlight to be turned on to HBCUs,” Hill told The Plug. “We have been in the realm of education and academics at HBCUs and we see the value, right, we can see it, but we haven’t had an opportunity to put the numbers associated with it to really talk about the long-term impact and the value added of having an HBCU [degree].”