The headquarters for Birane Seck’s independent coffee company, Jeef Jeel LLC, is his Brooklyn backyard. There, he has assembled an entire operation using only a smoker’s lighter, several shards of wood, cinder blocks that act as chairs and a makeshift stovetop.

Seck, a native of Senegal and a married father, has whipped up as much as 100 pounds of coffee in a single day as a sole proprietor. It’s hard work, but he loves it anyway. His ultimate goal for Jeef Jeel is to raise enough money to build a small community center to assist African families in poverty, especially children.

A microloan of $10,000 from Kiva, a nonprofit peer-to-peer loan service, is helping Seck achieve his dreams. The nonprofit was formed in 2005 and has primarily worked internationally, but some of their work is now being tailored to U.S. entrepreneurs who lack access to capital, particularly minorities.

Accessing Capital on Kiva

According to several studies on socioeconomic inequality, African-Americans do not start small businesses at the same rates as whites and other minority groups. Lillian Singh, vice president for racial wealth equity for Prosperity Now (formerly the Corporation for Enterprise Development), says the historical context should be taken into account when assessing this issue.

“Because of racial economic inequality, because of racial segregation, the access to capital is different,” she said.

In comes Kiva. The platform hosts crowdfunders to loan money to borrowers and offers loans up to $10,000 at a zero percent interest rate. Borrowers can get to the fundraising stage within 30 days of applying for loans on Kiva, according to Katherine Lynch, senior manager of U.S. partnerships. Once they receive the money, borrowers have 36 months to pay it back.

“Kiva loans are crowdfunded by individuals in communities that are all socially or philanthropically driven. The emphasis is not that they’re trying to make money off the business. They’re trying to help people achieve their goals,” Lynch said.

In an interview, she also said some of the more successful loans start close to $1,000 and later grow in capacity once the borrower has proven an ability to pay the money back.

So far, Kiva says they’ve supported 1,692 loans to African-American owned businesses for a total of $8,732,775. This represents nearly 28 percent of all Kiva loans, with 69 Black entrepreneurs receiving repeat loans.

The majority of Kiva’s African-American borrower entrepreneurs are in New York City, followed by Oakland, Pittsburgh, and Detroit.

In terms of proportion, there are other cities that have fewer Kiva borrowers altogether but serve a primarily Black borrower base. Those cities include Baltimore, Chattanooga, Rochester, and New Orleans, which all have at least 50 percent of their Kiva borrowers being Black.

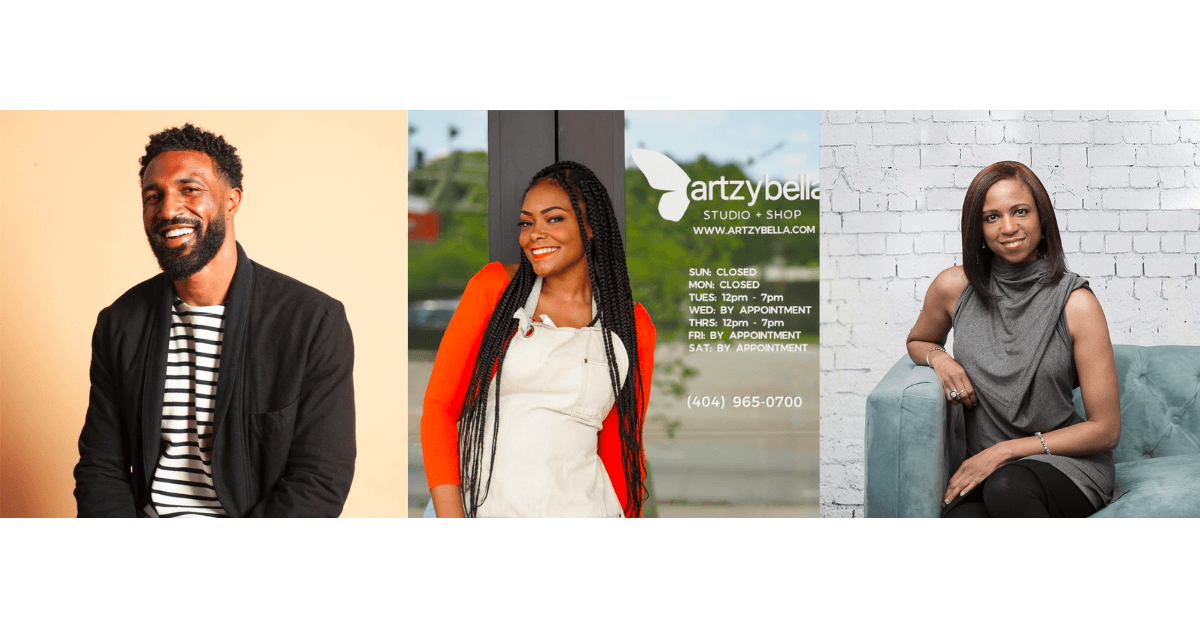

Partnerships Building Relationships

Brenda and Aaron Beener, owners of the restaurant Seasoned Vegan in Harlem, are also African-American Kiva borrowers. According to their Kiva page, the mother and son duo raised $10,000 from 190 lenders, which was disbursed in June 2018. The loan will help them purchase a new stove and oven combo, as well as other equipment.

Seck is also one of the entrepreneurs buried within Kiva’s data. Prior to launching his Kiva campaign to sell café Touba, a popular Senegalese drink, he received his bachelor’s degree in business in Senegal. Since then, he has successfully raised $10,000 from 88 lenders in October 2019.

Both loans to Seasoned Vegan and Jeef Jeel were endorsed by NYC Business Solutions Center through the Harlem Commonwealth Council, which acts as a trustee. Lynch said Jeff Hamer, a community organizer for the Harlem-based group, acts as an intermediary between Kiva and the borrowers in that partnership.

Lynch said Kiva has partnered with other local organizations, like the Build Institute in Detroit, to find entrepreneurs. Evan Adams, manager of capital programs at the Build Institute, said the Michigan-based organization reaches out to entrepreneurs, also acting as a trustee, by hosting competitions and conducting other programs.

According to one estimate, the Build Institute-Kiva partnership, since 2013, has helped 100 borrowers of all races receive nearly $600,000. About 86 percent of the entrepreneurs paid back the loan.

Lynch said Kiva’s goal as a nonprofit is to give entrepreneurs a chance by acting as “the first rung of the capital ladder.” Because of this approach, Kiva’s repayment rate across the board is closer to 80 percent.

Still, they’re comfortable with that figure because they are reaching out to communities that have historically lacked access to bank loans or other lines of credit due to potential prejudice or issues with data-driven algorithms that may be biased against people of color, Lynch said.

Experts like Singh from Prosperity Now is a proponent of these kinds of partnerships, microloans, Community Development Financial Institutions Funds and other alternative funding options for Black business owners. She says that states and municipalities should do more to increase support in places like Atlanta and Wilmington, due to their large Black populations.

Singh, however, also cautions against the belief that microloans are a simple solution to the problems of generational poverty and discrimination in the United States. She cited the Prosperity Now data scorecard, which tracks inequality by location and policy issue, to describe the uphill battle that many entrepreneurs face.

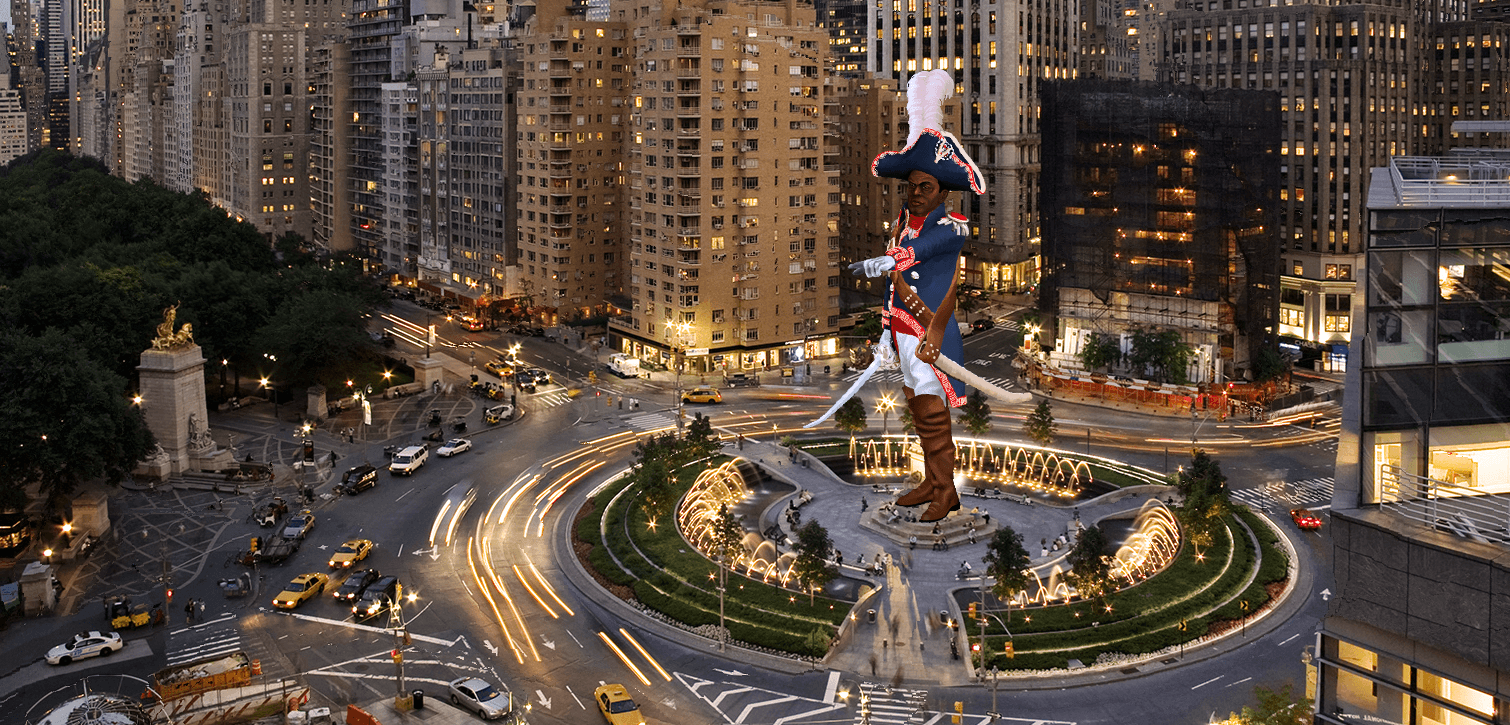

Even so, Black borrowers are taking matters into their own hands to build up wealth within their own communities. While researching data for this story, Lynch said she stumbled across a self-organized Kiva lending team called Juneteenth.

The group is composed of 14 individuals, mostly Black, who have collectively loaned more than $11,000 to more than 350 campaigns. They have assisted entrepreneurs in the food, retail, construction and service industries in the United States, Kenya, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, according to an impact report.

“It’s special because it’s demonstrative of lenders that are able to galvanize their participation with the theme of social justice,” Lynch said.