Since 2019, historically Black colleges and universities have produced nearly 100 patents, a recent analysis by The Plug found. But a patent can be more than just a shiny plaque on the wall — HBCUs are capitalizing on the innovation and research on their campuses through commercialization and licensing deals.

“It’s a new stream of business here in the 21st century,” Reis Alsberry, Director of Technology Transfer and Export Control at Florida A&M University, told The Plug.

“We should be capitalizing on all the research that’s done at HBCUs just like the other schools,” said Alsberry, who is in charge of turning FAMU’s intellectual property into revenue opportunities.

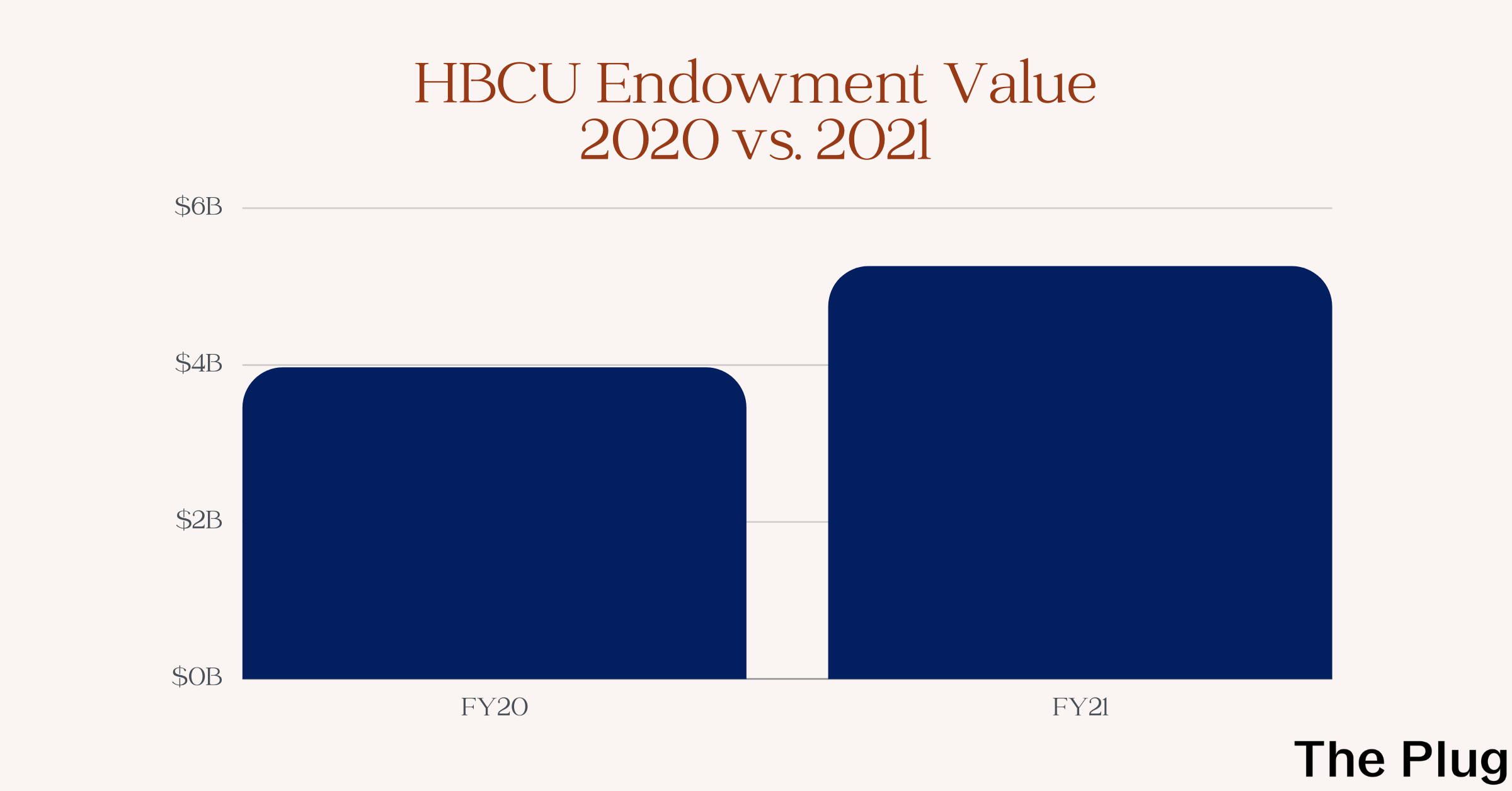

Schools like Stanford University, the largest single producer of patents of any university or college in 2020, received $114 million just in gross royalty revenue and equity from its technologies. But there are barriers when it comes to HBCUs creating as many patents as other institutions and securing revenue from their intellectual property. Just the cost of applying for one patent can set a school back $20,000.

“It’s really difficult for universities, particularly HBCUs, to make that a huge focus, especially if we are already under-resourced,” Almesha Campbell, Assistant Vice President for Research and Economic Development told The Plug. Campbell is also tasked with monetizing research as the school’s Director for Technology Commercialization.

This disparity in funding and resources for HBCUs is paradoxically why intellectual property protection and commercializing research can be so critical.

Licensing deals and other corporate or government partnerships can help recoup the costs of patent applications, provide another source of revenue for the schools, provide funding for the school’s foundation, help professors reach professional goals, aid in recruiting top researchers and secure government funding for future projects.

“If we don’t [commercialize], we’re going to be left behind,” Lavonya Jones, Student Programs Director for the Morehouse College Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center, told The Plug. “We have just all this intellectual talent that just falls to the wayside, it goes un-utilized.”

Commercialization can also have other goals beyond revenue.

“It is our intent to really make an impact upon the world and not just generate intellectual property,” Terry Adams, Head of the Intellectual Property and Innovation Unit at Howard University, told The Plug. “Having patents that are developed into products and services that are being put into the marketplace is where you begin to have impact.”

Some of the technologies in Howard’s portfolio include medical devices, AIDS treatments and a deal related to a large electrical grid system that Adams did not elaborate on.

At FAMU, Alsberry is working on commercializing some of their agricultural innovations, like two new types of grapes researchers created.

For Jackson State, some of the technologies they’ve been able to bring to market include tracking devices that help locate fishermen to make sure they are safe and military technologies.

In the 11 years Campbell has been heading up technology commercialization at JSU, she estimates her office has brought in $10 million to $15 million in revenue for the school.

But having a focus on turning research into revenue begs the question: will commercialization potential be the driving decision in what research a university funds?

“Not so much,” Adams said about Howard’s research. “When we go after funding it’s related to the interests and capabilities that our research faculty have in particular areas.”

Though researchers may be capable in some areas, they are not always entrepreneurs. Adams and Campbell have tackled this by creating incubators and accelerators to help them develop business plans and all the fundamentals of creating and running a startup.

“If no one is training them to think entrepreneurially or to think about commercialization, then all you would have is a bunch of patents sitting on the shelf and nothing happens to them. Then that would be a waste of time for an institution like mine that is already under-resourced,” Campbell said.

But it is not just faculty that have innovative ideas. Cleanstraww, a water purification device with a filter that can take lead and other contaminants out of your drinking water, was developed by a Jackson State student that Campbell helped mentor.

Students at Morehouse College have been able to develop businesses through the Morehouse Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center that have gone on to be funded by companies like Y Combinator.

The private sector is also trying to capitalize from the research and innovation HBCUs create. In August, a new VC fund, HBCU Impact Capital, launched with the goal of helping develop innovation by investing in businesses started by alums and people in the HBCU ecosystem.

Technology transfer and commercialization is a key piece of the puzzle for HBCUs to get onto a more equal playing field with its peer non-HBCU institutions.