Stand. Deliver. Take home a bag.

Since ABC’s Shark Tank premiered in 2009, the proliferation of similarly-fashioned pitch competitions have made their way across the world’s university campuses, nonprofit business initiatives, and tech company public relations stunts, turning business-building into a form of edutainment.

Today, nearly every city is remaking its image into the next version of Silicon Valley, hoping to attract local and national attention by defining their next startup success story. It’s akin to cashing in on a Shark Tank-fueled update of the American Dream, a la pitch competition.

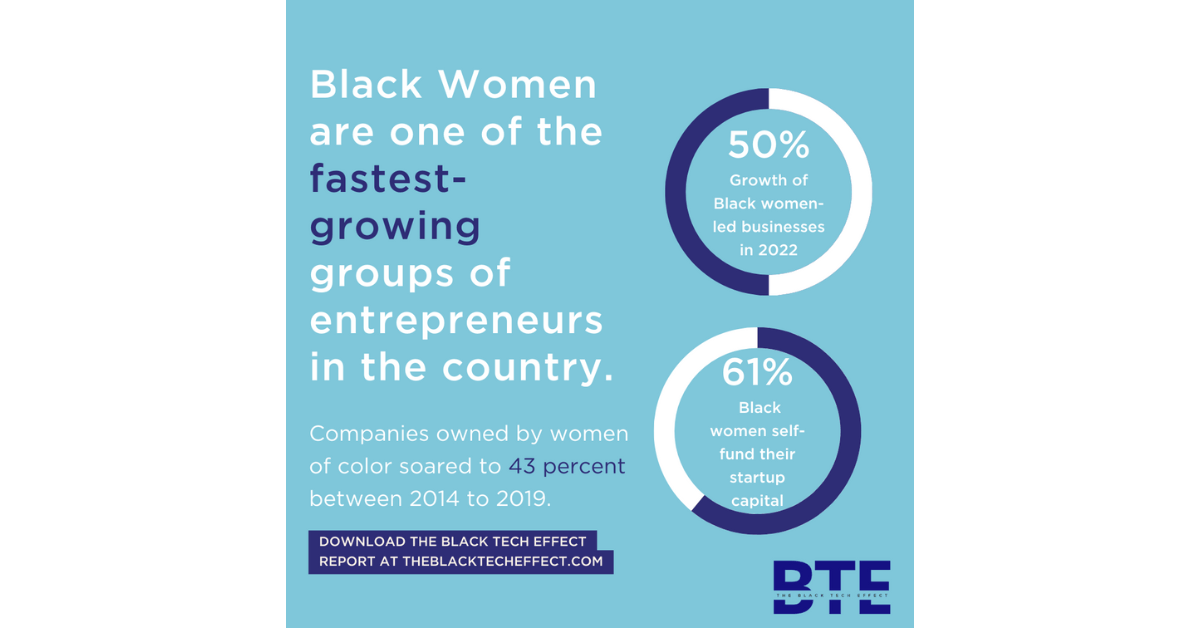

Black founders particularly are gaining entry to the startup world via competitions as they build their companies. The contests allow them to gain ground and front-row access to investors, potential customers, press features, and networks that have the potential to pay dividends.

Though pitch competitions offer access for all types of companies and founders, they are nowhere near an adequate response to what is a national crisis of inequality in funding for Black entrepreneurs. Racial wealth inequality and dismal statistics of Black founders being severely underfunded when it comes to bank lending and venture capital are not usurped by a Black founder’s ability to win money in a competition.

MONEY TALKS

Not all pitch competitions are created equal. Prize pools can range from a few hundred dollars to over $100,000. Some offer mentorship to founders in lieu of cash, using the pitching model as part of a process to help founders better learn how to articulate their value proposition to investors.

Dawn Dickson, CEO of intelligent vending machine software company PopCom, has won several thousands of dollars from pitch competitions through the years. She estimates that she’s taken home over $80,000 in equity-free money from various entities. Last year, she won $125,000 in a convertible note from Metropolitan Economic Development Association, a business consulting nonprofit in Minneapolis, but decided not to take the money as the terms didn’t work for her business. She’s since raised over $1 million in equity crowdfunding. Without question, the competitions launched her into the social media and media spotlight, making Dickson a recognizable name in the startup world.

“I’ve seen a lot of new pitch competitions come on the scene as of late. Some of it feels like hype or almost like a made-up storyline for a reality show,” says Rodney Sampson, an investor and CEO of Opportunity Hub headquartered in Atlanta.

Competitions that offer real money and attract high-quality investors appear to offer more value than, say, an organized event that simply provides social media fodder and bragging rights but no ongoing support in getting to the next milestone.

Melissa Bradley, managing partner of the Washington, D.C.-based 1863 Ventures accelerator program, recently led the D.C. HerIMPACT competition and awarded $50,000 in equity-free cash prizes to three women-led social entrepreneurs.

The prize money of these competitions must be worth the time, effort, and time away from focusing on the core business for it to make sense to Black founders to participate, says Bradley.

UNDERREPRESENTATION

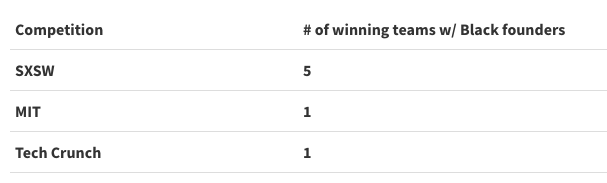

While local city events and dollars can give startups access to equity-free capital, when it comes to winning out on the country’s biggest stages, very few companies built by Black founders are cashing in.

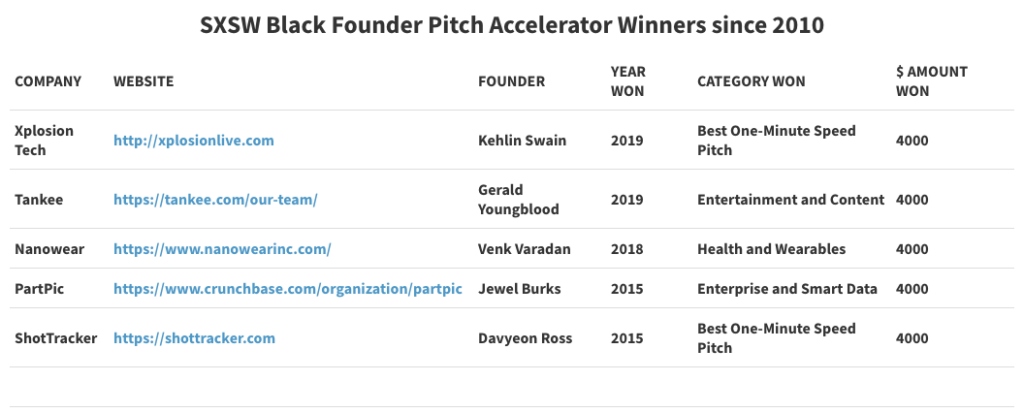

The annual SXSW interactive festival attracts hundreds of thousands of people to the city of Austin over a two-week period, with thousands of applicants hoping to land a spot in their coveted Pitch Accelerator competition. The competition provides $4,000 to 10 winning teams and two complimentary passes to the conference the following year. Created in 2010, the competition has awarded over 80 startups; just five of these had a Black founder of co-founder. Of those Black founders, just one, Jewel Burks, who won in 2015 for her company PartPic (sold to Amazon in 2017), had a female founder. From 2010 through 2014, there were no Black winners in any of the cycles.

The MIT $100K pitch competition has been operating annually for the last three decades, awarding some of the most forward-thinking technology companies $100,000 in equity-free prize money. In its 30-year history, only one company, 3dim, who had one Black founder, has won the grand prize.

TechCrunch Startup Battlefield also awards $100,000 in a non-dilutive grant to winning teams and hosts pitch competitions in San Francisco, New York, Berlin, London, Beijing, and other cities around the world. Since 2010, between their San Francisco and New York competitions, just one company, Forethought, had a Black founder that has won in America.

See our full analysis of each competition here.

We are blind in understanding the demographics of who actually applies to participate, who makes it through the initial vetting processes, and who ultimately gets a chance to compete on stage. Are Black founders applying to top-tier competitions enough? If so, why aren’t they getting past the initial vetting stages and making it through to the top?

According to an email exchange with the organizers of MIT’s pitch competition, the institution does not collect demographic data on winners or applicants. Assuming this lack of demographic data collection rings true for most competitions, there is little we can discern as to why more Black founders aren’t making their way to the top of the winner’s circle, or what barriers are preventing them from doing so.

PLAY THE GAME…WELL

How founders decide to get to gold is multifaceted, and the ability to navigate pitch competitions and turn them into assets that will help reach significant milestones is a personal choice every startup will need to fit into their growth plan. For Black founders living in cities where access to capital is a challenge based on the economics of the market, taking the plunge to enter a new market through a pitch competition could help to advance the business and should be sought out as an entry point to expanded networks.

“Money doesn’t walk, you’ve gotta go and get it. There are hundreds, maybe thousands, of pitch competitions around the world,” says Sampson. “Apply and get there, as sometimes you have to build outside of your base if your base isn’t writing checks, issuing contracts, or buying.”