KEY INSIGHTS:

- At first glance, the challenges against race-conscious admissions may not seem like they have direct implications for HBCUs, but there are potential positive and negative impacts.

- If the Court rules against affirmative action policies, it may push more students to enroll in HBCUs again.

- But just like affirmative action, HBCUs were born from trying to right the wrongs of segregation, so some worry they could be targeted next.

Last week, lawyers for Harvard University and the University of North Carolina defended affirmative action in front of the Supreme Court in cases that will likely change the face of higher education.

At first glance, the challenges against race-conscious admissions may not seem like they have direct implications for HBCUs, whose median student body is about 20 percent non-Black, according to an analysis of national education data by The Plug. But look deeper and there are potential long-term impacts to HBCUs — for better and for worse.

The history of affirmative action

The modern form of affirmative action was born from the Civil Rights Movement, with President John F. Kennedy first using the term in a 1961 executive order which mandated government contractors “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.”

Three years later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prevented any program in the U.S. that received federal funding from discriminating on the basis of race, color or national origin. The Department of Education regulations enforcing this law mandate that institutions which previously discriminated based on race or nationality “must take affirmative action to overcome the effects of prior discrimination.” Over the last five decades, these policies have worked to increase the number of minorities accepted into predominately white institutions.

HBCUs by their very existence are evidence of this previous discrimination.

“We were born of segregation, not of choice, but of segregation — exclusion of our people from educational opportunity,” Roslyn Artis, President of Benedict College, told reporters at a dinner in August. “We were places of hope and opportunity for people who did not have a choice otherwise.”

But the legal gains of the Civil Rights Movement led to declining enrollment for HBCUs since Black students had the opportunity to attend a larger pool of schools, scholars argue. Previously a “critical mass” of Black Americans attended HBCUs, but by 1976, just 18 percent of Black students were enrolled in HBCUs. In 2021, that number was down to 7.4 percent, an analysis by The Plug of national education statistics found.

Reversing the trend?

When the Supreme Court announces their decisions in the Harvard and UNC cases, likely next June, experts think the Conservative super-majority will strike down the schools’ affirmative action policies, which the group Students for Fair Admissions alleges discriminate against white and Asian applicants.

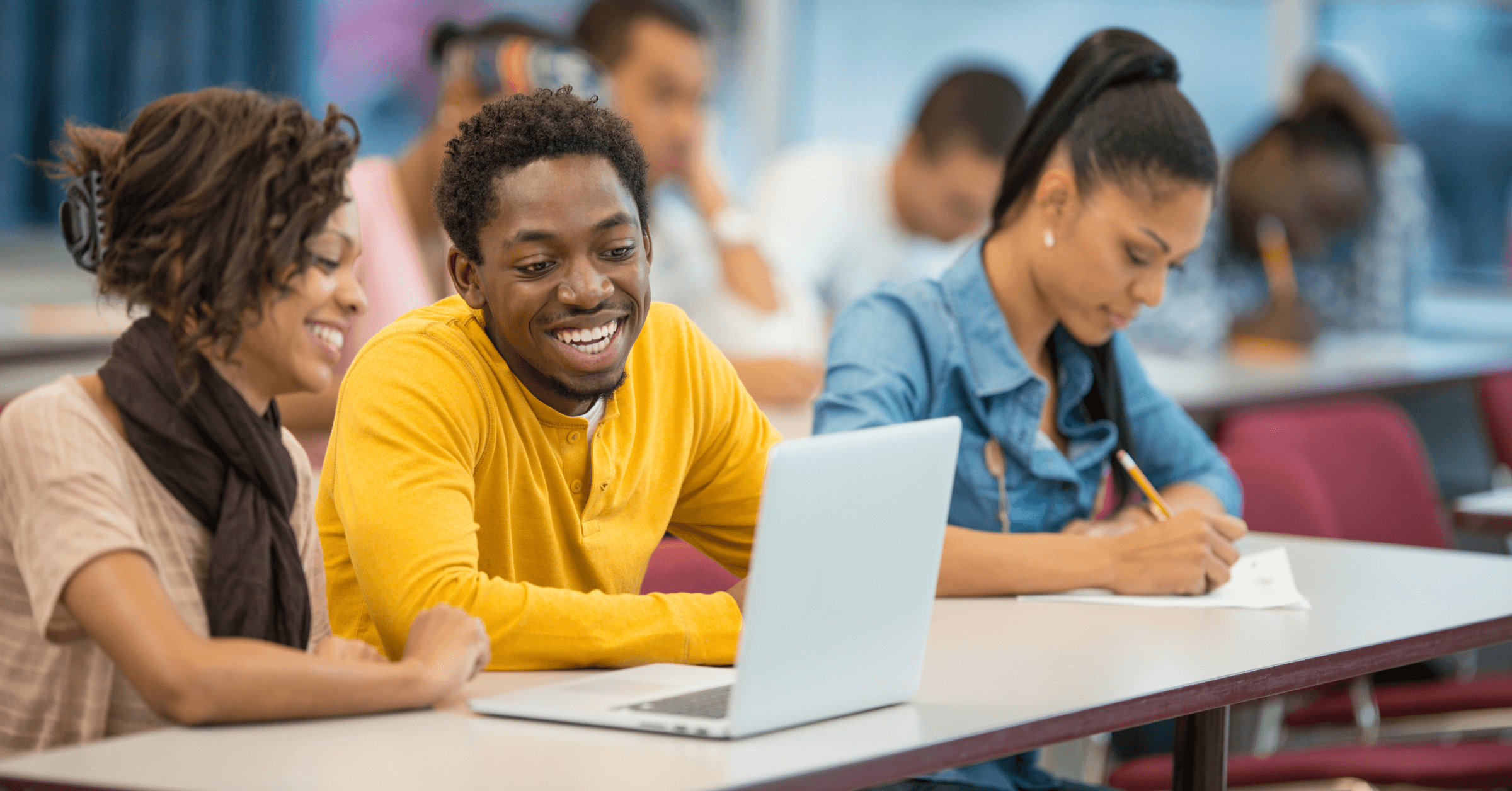

If this happens, other universities may try to pre-empt any legal challenges and drop their own race-conscious admissions policies which may push more students to enroll in HBCUs again.

“There can be a lot of thinking that were affirmative action to continue to be diluted, that it would drive many of our students back home,” Artis said.

We have already seen major social change drive more students to HBCUs. Over the past two years, since the protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd, there have been increased applications and enrollment to HBCUs. In October, Morgan State University announced it had reached the highest enrollment at any point in its 155-year history.

If affirmative action ends, it is likely more prospective students will proactively decide to go to a college where they feel safe and wanted.

“I think that anticipating that they may encounter a hostile environment, it can drive them away from institutions, even if the institutions have declared that they want to try to attract a diverse student population,” Shirley Malcom, a board member of Morgan State and director of the American Association for the Advancement of Science SEA Change program, told The Plug.

“I think at the end of the day, it’s just not where they go, but where they stay and where they are successful,” Malcom said. “So to the extent that they are able to find a space where they can find community, where they can identify a place that looks like they want them and they welcome them, that is where students are likely to want to end up.”

The next target?

The potential end of race-conscious admissions raises existential questions. Just like affirmative action, HBCUs were born from trying to right the wrongs of segregation, so some worry that in this current political atmosphere of critical race theory bans and widespread bomb threats against HBCUs, activists may set their sights on them next.

“Do we have to be concerned that someone would try to twist the narrative in a way that would harm HBCUs, particularly those public HBCUs? Absolutely,” Artis said, highlighting the particular vulnerability that public colleges face because they rely on government appropriations for more of their funding.

“So if the worm is turned, so to speak, and we decide that we want to be entirely pluralistic and we want to eliminate every vestige of segregation, could someone argue that HBCUs are that? Of course, we have to be concerned about that. I think that’s very likely, and particularly for our public peers,” Artis continued.

But Malcom, a Black woman who was raised in the South under Jim Crow laws, says these arguments are not new.

“I remember the days after the higher education institutions in the South started to open up the previously all-white [schools], these questions were raised within the states,” she said, adding that those questions became a kind of foundation of under-resourcing HBCUs because students “can now go to the white institution.”

But research shows HBCUs are as important now as ever, from having protective effects on Black Americans’ well-being to producing more Black STEM graduates and countless other immeasurable impacts in the daily lives of students and alumni.

Next summer, when the Supreme Court rules whether or not they think Harvard and UNC’s policies are constitutional, Malcom believes that will not be the final word.

“It can lead one to despair or it can mobilize,” she said. “We need to keep our eye on the opportunities to support excellence, equity, diversity, inclusion, accessibility — no matter what happens.”