KEY INSIGHTS

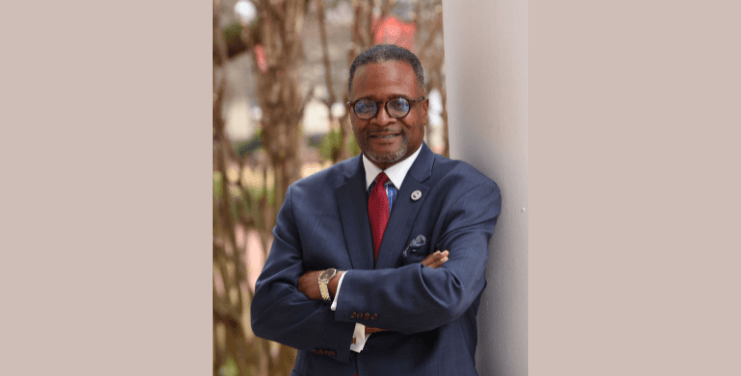

- In late April, President French celebrated his formal investiture as the leader of CAU, more than two years after his original ceremony was waylaid by the pandemic.

- Before the ceremony, he laid out his vision for the future of CAU.

- His plan includes increasing research dollars to $100 million, opening a law school and more.

This is the latest installment of The Plug’s series of periodic deep dives with the executives and organizational leaders driving change, The Insight. Read our previous installments with the Presidents of Morehouse College and Paul Quinn College, and the co-founder of the #BlackTechFutures Research Institute.

It may be macabre, but facts are facts: George French Jr.’s professional milestones have happened around funerals.

When I mention this to him, as we sit in plush leather armchairs in his office at Clark Atlanta University, the school’s leader sinks slowly back in the chair, a thoughtful look on his face, then softly recites part of a Bible verse.

“‘In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord high and lifted up.’ That man had a revelation at a funeral. You’re so right. I never thought about that,” President French said.

The reference comes easy to a man who was a minister before going into higher education. But a chance encounter at a funeral with the president of the Alabama-based HBCU Miles College made President French pivot his career.

Late last month, more than 25 years after that encounter, President French was celebrating a career milestone the same week he had to bury his friend, mentor and first president of CAU, Thomas Cole. Just days after the funeral, President French celebrated his formal investiture as the leader of CAU, more than two years after his original ceremony was waylaid by the pandemic.

Before the investiture, he sat down with The Plug for a wide-ranging conversation touching on becoming president during a crisis, how he views receiving donations from organizations with histories of discrimination, his dream of a law school at CAU and how the school is preparing students for the future of work.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

—

Mirtha Donastorg: How did you first come to higher education?

President French: Through ministry. I was the pastor of a church in South Boston, Virginia, and one of the bishops of the church died. So while pastoring when he died, the whole church came, and the President of Miles College [Albert Sloan] came to the funeral. He asked me to pick him up from the airport and we hit it off. He asked me to leave Virginia, to leave law school. President Sloan invited me to come to Miles College to be his director of development.

After I was there for two years, I was visiting with Tom Cole, President of Clark Atlanta University. He was meeting with the President of Miles College, they were best friends, and he had me in the room the whole time. President Cole would ask me questions every now and then and I didn’t know where he was going with it.

So President Cole says to the President of Miles, ‘You need to get George into that [HBCU presidential leadership] program. He could be a president, and he should be a president.’

When you talk about God, I buried this man yesterday who told my president then I need to be a president and put me on track to be president, and I wind up giving him the highest honors, burying him right on this campus.

What year did you join Miles College?

1996. And in 1998, that September, President [Sloan] took me to lunch. He said, ‘I’ve never had anybody work for me that I would want to succeed me as President.’ From that day forth Mirtha, every day I was with him. Every meeting he had. I was his right hand. And he announced publicly that he wanted me to succeed him several times, it was no secret to anyone.

So he calls me one day, he says, ‘George we have a board meeting tomorrow, I’m going to need you to handle the board meeting because I’m in the hospital.’ I said no, that’s too much exposure. I said, ‘If you’re not going to be at a board meeting, we need to cancel because we don’t need to have a board meeting without you there, that’s how presidents lose jobs.’ So he said, ‘Well, let me call you back.’ Ten minutes later, his wife called me back and said he just died. Just like that.

The board did a search. The president of Alabama Power asked for a meeting with the chairman of the board. White guy, very influential, great guy, Steve Spencer. He said ‘Listen, we are in the middle of a capital campaign and in the middle of a capital campaign, you need to have leadership. We need a president and I’ve spoken to the corporate community, white corporate community, and they agree you all need a president and that president needs to be George French.’ They called off the search and named me president. I never applied.

Did you want the job?

Mmhm. But I wanted my friend to be alive more.

So that’s how I got into higher ed. Long story.

It was picking President Sloan up from the airport, driving him around for a few days and that changed the course of your life. I don’t know if this is macabre or dark, but it’s interesting that these pivotal points have happened around funerals.

‘In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord high and lifted up.’ That man had a revelation at a funeral. You’re so right. I never thought about that…

So, [the board of Miles College] named me acting president and they let me speak at [President Sloan’s] funeral. It was the only standing ovation of 5,000 people during the whole funeral. It was so powerful that I knew it wasn’t me and I knew it had to be ordained. And on that stage when I turned around, the trustees were sitting on the stage, they were huddling up right there and I said, ‘They’re about to name me,’ and that’s what they talked about right on the stage, right at the funeral.

You were at Miles College starting in 1996, in 2006 became president of Miles and then in 2019, it’s announced that you are going to be the new Clark Atlanta President. What made you decide to leave Miles?

That I was comfortable. I reached my 10-year goals within the first two years. Eight years ahead of schedule. So I started doing other things, I mean, building, buying properties. We about tripled the size of campus by the time I left. I really reached all the goals.

When I tell you I was so comfortable at Miles. But that was the point. It was just it was gonna be too comfortable. There was really no challenge.

Did you want to be at Clark, did you want to be in Atlanta?

I always wanted to be in Atlanta. I always knew I wanted to be here. So what was cool is my son graduated from Morehouse, my daughter graduated from Spelman, and she was at Spelman when I took the job. So she used to walk right across the street, sit in that chair and do her homework. For me to be president here and she’s doing her homework, then we leave and go to lunch. Those were good times.

So you joined Clark Atlanta in September 2019. A few months later, the pandemic hit. How was it being in this new position at a new school and guiding it through this once-in-a-generation pandemic?

Well, that was the second crisis. The first crisis was actually when I arrived.

My mother actually told me, she said ‘I was praying and when you accept that Clark Atlanta University presidency, one of your first responsibilities is going to require your pastoral skills rather than your administrative skills.’ I didn’t know where that was coming from.

And then this young lady [Alexis Crawford] was tragically murdered, one of my students, and I ministered to the family such that they asked me to do her eulogy. They had a pastor, they had a church, they hadn’t met me before this happened, but I ministered to them. So I wound up having to pastor to the community, to the entire Atlanta community, to that family and to this [CAU] community. And people began relying upon me much earlier than they planned to. This crisis forced students, the administration, [the] community to rely upon me when they were planning on pushing back until they saw my hand and how I do things.

So you worked in HBCU fundraising for a very long time, since the 90s. How have you seen donors’ perceptions and relationships to HBCUs evolve over that time?

I had the fortune of seeing institutions support HBCUs because it was a moral imperative. ‘We’re making great money as a corporation, let’s be good corporate responsible citizens and give money to the HBCUs because it’s the right thing to do.’

Today, what I’m seeing is that empirical data indicates the value of HBCU graduates within different communities, including the corporate community. They wind up adding some more value to the C-suite conversation.

So now it’s about an investment. Before it was about a gift to help the organization. Now it’s about an investment and as you know, with an investment you expect a return. So, if you invest, you expect that Clark Atlanta University is going to have those students prepared for the workforce. We give you this money and you enhance capacity, and they’ll be sharper when they come to us and they’ll be more ready. It’s become now more of a business proposition than a moral imperative, which is a good thing.

I know that after the summer of 2020, a lot more attention and money was given to HBCUs. How do you as president balance receiving money and opportunities from corporations, organizations that we know have the money, have the opportunities but also have recent or historic allegations of discrimination?

You’re correct, like the Koch brothers [for example]. When that was a big deal about the United Negro College Fund accepting the Koch brothers’ money, I actually weighed on a national news platform.

And my thing was, yes, I am familiar with the past discrimination of the Koch brothers. But If they want to invest in this community, I would not deny a young boy or girl the opportunity to get a university degree because the money comes from someone who discriminated against someone else.

With the investiture, what does that mean for you and for the university? Especially considering the funeral that you had to hold this week for President Cole.

I have an opportunity to do something that’s unique as far as investitures. Ninety percent of all investitures involve a president making promises about what he or she is going to do. I have an opportunity to report out what I have done over the last two and a half years, and then paint the vision for where we will go into the future.

What it means for me is to celebrate coming through COVID, to celebrate the onboarding into the Atlanta community, to demonstrate based on the successes of the administration, thus far, to demonstrate that the momentum will continue to exponentially increase. And that it’s really our time.

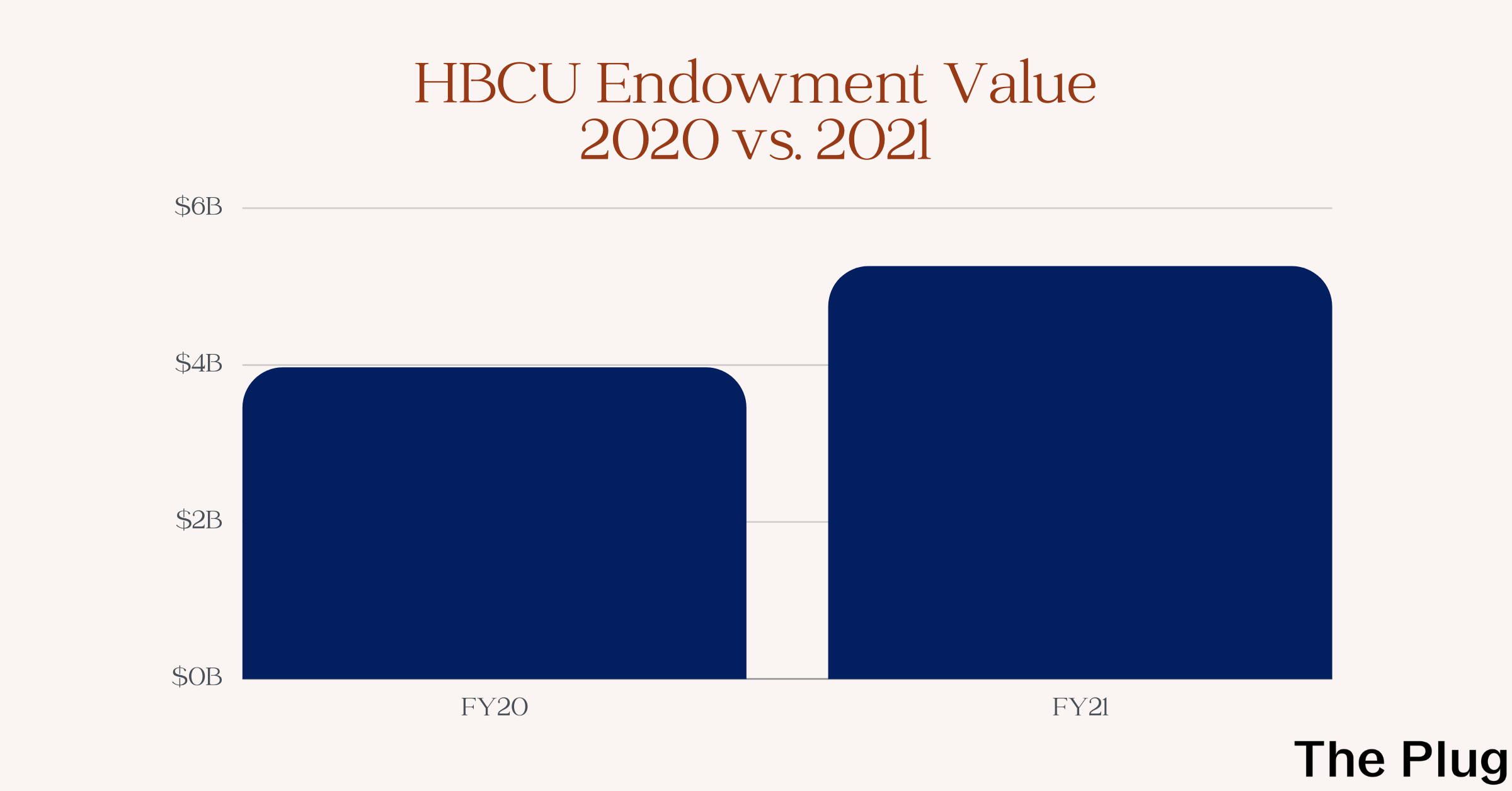

We brought in $200 million in the last two and a half years, and that’s in the middle of COVID. We just kicked off the comprehensive quarter-billion-dollar comprehensive campaign. So, this is a celebration.

What it means for me providentially Mirtha is that it feels like an anointing with my mentor, burying him on the first day of inauguration, and then the end of the week, being invested. Just to have him to open my week, it just seemed providential.

So you mentioned talking about the future during your inauguration. What is your vision for Clark for the next five, 10 years?

The goal is to exponentially increase research dollars, to go from about $8 million to at least $100 million a year in research.

Are you trying to be an R1 institution?

That’s the aspirational goal.

And the monetization of our real estate portfolio. So we basically are the largest landowner in the West End. Some of these properties we need to sell off, some of them we need to ground leases with public-private partnerships and we need to bring all of our properties online.

Now how do you think Clark Atlanta is preparing your students for the future of work?

I think that we have work to do in that area. I think that it is not the best business model for deans and professors to go into a room and determine what the curriculum needs to be for students without going to the marketplace and finding out what the needs are.

So in the last month and a half, I met with about 10 different technology companies, large ones from Microsoft to Google to some smaller ones, to ask them what’s going on in that back room, on those boards?

What are the skill sets that my students would need to work for your company, so they can come out and be ready? What are those skill sets? What classes do they need to take?

So I think we have to make sure to align the curriculum with the needs of the marketplace. That’s what we have to do better. We are enhancing that now with partners like Apple, who will build the Propel Center, which will be the international hub for innovation for HBCUs and be somewhere within Atlanta University Center.

What’s happened with the student housing?

We’ve done some restructuring in that area. We’re ready. We’re preparing now. As soon as the semester is over, we have a team in place that’s going to refurbish, and we’ll be ready. My administrative cabinet will move into dormitories a month before school starts, we’ll sleep there for some nights and we’ll observe ourselves and see if there’s anything that needs to be done. That’s how we’re going to make sure we’re not going to do what we did last year.

Are you thinking of opening a medical school? I see the osteopathic medicine books on your table.

My daughter is a [doctor of osteopathic medicine] and I sent her pictures of those, I was so excited to see those. So no, I’m not thinking about doing that. What I would like is a law school.

Is that something that you’re working towards?

Yes. But it’s not on my strategic plan, the board hasn’t approved it. It’s a dream of mine.

While we continue to excel, what I realized is that I’m not going to be able to make Clark Atlanta University the number one HBCU in the nation on any charts, not during my tenure. But with there only being [a few HBCU] law schools, if I start a law school, I can make the law school number one. I can do that. Howard [University] still is number one, but I can overtake Howard if we do it right because we’re in Atlanta.

Because of the benefits from the Black intelligentsia that Atlanta has?

Right here, right here! You want to see something exciting? You walk out there on that promenade. And you see students from Clark Atlanta, Spelman and Morehouse College and medical students, and they’re from everywhere, and they’re so bright.