One of the earliest documented Black-owned and operated venture capital firms, Syncom Venture Partners, set up shop in 1977. Headquartered in Silver Spring, Maryland, the firm is responsible for some of the earliest investments made in well-known formerly Black-owned telecommunications and media companies, including Black Entertainment Television (BET) and RadioOne Interactive.Founded by Herbert Wilkins Sr., a former venture capitalist, Syncom trailed the end of the 1960s and 1970s Black Power movement. The distinctive almost two-decades-long moment in the nation’s history presented a climate of many firsts: From the civil rights act to voting rights among Black Americans to affirmative action, which opened up the doors to Corporate America and ushered in the Black middle class, these defining decades, while hard-won, uniquely aided the progress for Black people, historically locked out of American capitalism, around the country.

Black businesses also saw a slight lift in opportunities from government intervention. The Small Business Association (SBA), a major catalyst in supporting the needs of business owners in their funding and growth, was established in 1953 but benefited white-owned businesses. In 1969, under President Richard Nixon, the U.S. Department of Commerce provided federal backing to minority businesses through the Office of Minority Business Enterprise (now the Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA).The initiative dedicated federal contracts to minority-owned firms, opening new doors for capital, though a limited pool, to circulate to Black businesses. By 1972, following the publishing of the very first survey of minority-owned businesses and enterprises, the U.S. Census Bureau tracked that of the 322,000 minority-owned business enterprises in existence, one-half were Black-owned with receipts of $4.5 billion. A change was on the horizon.

The Growth of Black Venture Firm Ownership

The number of Black-owned venture capital firms and its cohort of Black investors has grown substantially over the last 50 years. Today, over 80 documented Black-owned firms and over 200 investors from diverse ethnic backgrounds represent a sector in the industry uniquely burdened by both race and duty. They face both discrimination and distrust in the asset management field, while also carrying the responsibility of correcting the industry’s historic ills of disproportionally being unkind and underfunding Black founders and women across the board.

Black-Owned Venture Capital Firms

A 2019 Stanford study, in collaboration with private investment firm Illumen Capital, found that when professional investors rated stronger white-male-led team marginally higher than the stronger-quality black-male-led team.

There was a competitive dynamic to the study. We wanted to capture the true way in which people invest‚ and they would consistently choose the white-led fund manager, explained Daryn Dodson, managing director of Illumen.

Further up the stream of VC asset management is allocation, particularly the disproportionality when it comes to Black founders. Data on the lack of venture dollars to Black founders, and particularly Black women, have harkened many a news story and panel discussion on the state of discriminatory venture capital.

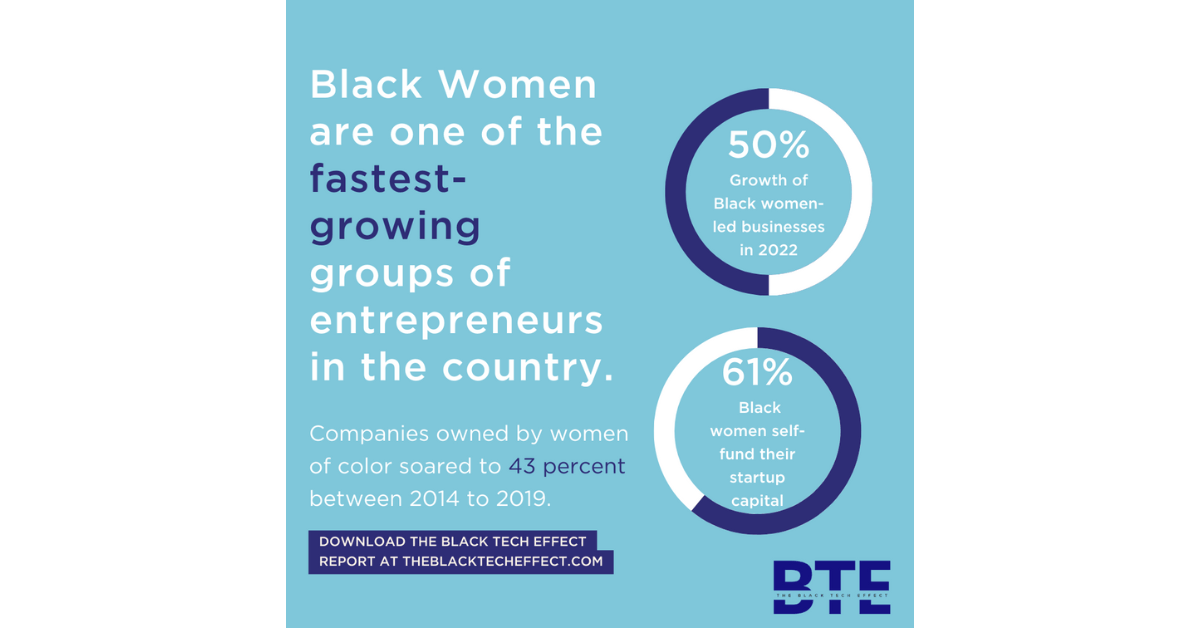

Who is getting access to funding, and who isn’t, has illuminated both past and present research with media and industry associations. When entrepreneurship support organization Digital Undivided dropped its Project Diane report in 2016 detailing that it had only found just 24 Black women who had successfully raised venture capital between 2011 and 2014, it had been the first to examine the less than 1% of capital invested in Black women founders. An August 2020 report via Crunchbase found that Black and Latinx founders had raised $2.3 billion collectively, but represented just 2.6% of overall funding ($87.3 billion) invested that year into private firms. The visibility of data has provided succinct nudges, namely timely displays of change fashioned to right the wrongs.

Documenting funding disparities is shedding light on discriminatory practices. This has meant more funds targeting entrepreneurs of color and specifically Black women. Public and virtual spaces have emerged with fervor, with discussions centering the need for venture capital to push past its biases in order to increase access to capital for Black entrepreneurs. Institutional funds from long-standing companies like Intel, Citi, Goldman Sachs, and others have aimed their efforts to engage underrepresented minority founders through funding, mentorship, and general support.

The targeted efforts increased exponentially following the murder of George Floyd by police officers in May of 2020, when long-standing firms like SoftBank, Andreessen Horowitz, Google, and others immediately launched opportunity-centric funds targeting Black and other underrepresented founders. However, addressing the issue of disparity and discrimination only scratches the surface of how Black founders experience and engage with the venture capital industry.

No Governing in the Wild

Aside from its documented history of racial and gender discrimination as an industry that is 89 percent male, the venture capital industry has long had an issue with its people. Before the #MeToo movement picked up steam, white male investors were becoming part of the public discourse on unchecked bad behavior.

Following these movements, #MovingForward emerged as an initiative supported by over 200 VCs to help founders report harassment, but widespread frameworks for regulation and accountability appear to be strictly voluntary. These missing factors have also been bereft in the Black funding community. Without accountability, some Black founders have said that, even in their experiences with Black investors where they assumed a level of safety and familiarity, run-ins with ill-behaved investors are still present.

Clarence Bethea, founder, and CEO of warranty coverage platform, Upsie, describes a meeting with a notable Black investor who publicly proclaims to be dedicated to advancing Black founders but had an experience that didn’t feel very empowering. He described the experience and the engagement as arrogant.

I’d followed this [person] for a while, saw him on the stages, but he continued to look at his phone during the entire pitch. He was arrogant and disrespectful, not because he chose not to invest, but because I’m a Black founder and he treated me like I didn’t matter, explained Bethea.

Bethea isn’t the only one with concerns about how they have been handled by some Black VCs or watched Black VCs don stages to talk about their support of founders but not actually writing checks. A rising founder, who asked to remain anonymous, said that he’s had run-ins with several prominent Black VCs and experienced similar treatment.

As one of the Black VCs pushing for more Black fund managers, [he] showed up 5-8 mins late to the meeting, didn’t apologize, and he kept texting on his phone for the bulk of the meeting. My cofounder ‘shut down’ after about 15 mins of him pretending to listen to us. The VC passed (obviously), eventually after poo-pooing on our business…We probably wouldn’t have enjoyed working together anyway, the source explained.

I avoid generalizations, but the consensus is that a few Black founders I’ve spoken to about this feel Black fund managers are particularly arrogant. That the desire of certain Black VCs isn’t really to change the inequity and skewed power dynamics of venture, they just want to be at the same ‘table’ with white male VCs.

Accountability isn’t standardized in the world of venture capital beyond the fiduciary requirements of compliance with the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC). Fund managers, with their growing social media celebrity status, are often heralded as saviors of American capitalism, and Black funders platformed as a result of their direct connection to the framework of wealthy white men: presumed business savvy, Ivy league university credentials, and/or proximity to other powerful white men. Oddly, considering the outcry of the #MeToo movement across industries, and high profile discrimination cases like investor Ellen Pao’s lawsuit against former employer Kleiner Perkins, changes to the venture capital industry have not since required standard background checks or publicly accessible behavior reports on individual VCs or firms themselves.

In a 2019 post on his medium page, Hunter Walk, general partner at Homebrew, suggested that founders themselves conduct background checks on VCs, but he has yet to find one that does one. There is no automatic formula for success among Black investors, even those who serve on teams that are proximate to notable white investors of notable white-operated firms. In fact, based on an analysis of these firms, while diversity metrics measure higher than counterparts, they still lack direct investment in Black founders.

And while bad behavior across the venture capital landscape is not particularly novel, particularly those who may wield more power, deeper connections, and experience, the idea that Black investors will present a softer, kinder, or more ethical practice solely based on their race directs the conversation away from the industry’s need for an overhaul within its behavioral and ethical policies.

An Option for Auditing

New tools like Rate My investor have recently emerged as a checks and balances user-contributed rating system which could provide additional transparency into the industry and help founders seeking to build relationships and land potential investments. Data validation requires that every submission includes verified relationships. Founders must submit pdfs, screenshots of text messages, or a copy of a term sheet to demonstrate proof of engagement with an investor. The database currently tracks over 50,000 investors with thousands of data points.

Advisors said we shouldn’t do this. A lot of investors are afraid of this,” Austin Stofer, founder of Rate My Investor, toldThe Plug. “They know they weren’t operating as they should have been. A lot are starting to launch new initiatives, and it’s just bullshit.”

Rate My Investor published its Diversity in VC report last year documenting the mostly homogenous groups of white males leading in VC. The world is really starting to really care about this. There’s a lot of flaws the way they are investing, Stofer said. Until we change the type of people that are analyzing these deals, how are these founders ever going to get their point across? Still in its early stages, after searching for 200 of the 277 known Black VCs in the industry today, none appear within the engine.

A Future of Accountability?

To distinguish themselves from the pack, Black-led venture firms could do well to raise the standard of behavior ethics aside from just declaring themselves at the behest of Black founders. Measurable and accountable data points and evaluations, shared publicly and frequently, could prove to create new frameworks that help Black and other underrepresented founder groups better navigate the harsh waters of venture capital and systemic racism and misogyny.

For some firms, evaluation tools and assessments around practices and impact are still nascent. Stefanie Thomas who leads investments at impact venture capital firm, Impact America Fund, says that her firm, and others, rely on internal evaluation tools they’ve developed and implemented over the years to further understand how they can better engage founders. The tracker allows their team to solicit direct feedback from founders, but admittedly, hasn’t yet been tied to performance evaluation, a next step Thomas says is important as the firm goes on to manage more funds.

Generally speaking, firms with a give first culture have a process. Think any VCs that strongly brand themselves as centering founders, explained Thomas. I can see [these assessment tools] becoming more critical as firms grapple with their own processes in how to consistently succeed at sourcing, funding, and supporting underrepresented founders.