For most of us, losing a photo ID is little more than a wasted afternoon at the local Department of Motor Vehicles. But for the 2.5 to 3.5 million Americans who experience homelessness every year, valid identification can be the difference between life and death. Applicants must prove their identities in order to access federal programs like Social Security and Medicaid and to legally work, open a bank account, or sign a lease. Lack of identification can even prevent people from entering temporary shelters. This issue disproportionately affects homeless people, who are among the most likely to be without vital documents.

In Atlanta, where 10,000 people experience homelessness on any given night, tech designer India Hayes, communications pro Amber McCain, and filmmaker Anita Jones are trying to solve some of these problems by helping them replace lost or stolen documents so they can obtain government identification.

The trio’s social enterprise, Mini City, launched in 2017 with a year-long pilot at the Salvation Army of Metro Atlanta — where they helped hundreds of people through the process of obtaining vital records. “Vital records are not typically top of mind for people when serving the homeless population,” Jones says. “We’re looking to fill that gap and allow people to take the next step out of transitional housing or off the street.”

The organization says it helps “streamline the process for access to voter IDs, birth certificates, social security cards, state IDs, and employment services.”

At last official count in 2016, 12 percent of the U.S. population—more than 40 million Americans—were below the poverty line. Nearly half of them live in absolute poverty, meaning their incomes can’t cover basic needs like food and shelter, and 5.3 million earn less than $4 a day, putting them on par with the world’s poorest. People of color, particularly black people, are disproportionately impacted: Though African Americans make up around 13 percent of the U.S. population, 42 percent of people experiencing homelessness are black.

A lost or stolen ID goes way beyond a homeless person’s ability to access services, according to Eric Tars, senior attorney with the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty (NLCHP). “Whether it’s eating, sleeping, or going to the bathroom—all of these can become criminal acts when performed in public,” Tars told me over the phone. “If you’re targeted for these activities and you don’t have an ID, you’re even more likely to be taken to jail and saddled with fines you can’t pay, which is just one more barrier to saving first and last month’s rent on an apartment.”

Putting ID administration back in the hands of homeless citizens gives them the power to break the cycle—and it also helps nonprofits do what they do better, according to Melinda Allen, former grants manager for the Salvation Army of Metro Atlanta, who now heads up grants and research at Must Ministries.

Like an increasing number of nonprofits that serve the homeless, the Salvation Army uses the housing first model—an assistance approach that moves people into permanent housing as quickly as possible. The average participant in Salvation Army’s Rapid Rehousing program spends 30 to 60 days in a shelter before moving into a permanent home, compared to the national average of more than 100 days. But missing vital records can slow things down significantly, which is why Allen says MiniCity can intervene.

“To get into permanent housing or rapid rehousing, you’re signing a lease in the individual’s name, so that person needs an ID card,” Allen told me over the phone. “Being able to help someone access an ID card within that 30 to 60 days plays a large role in meeting the end game of stable housing.”

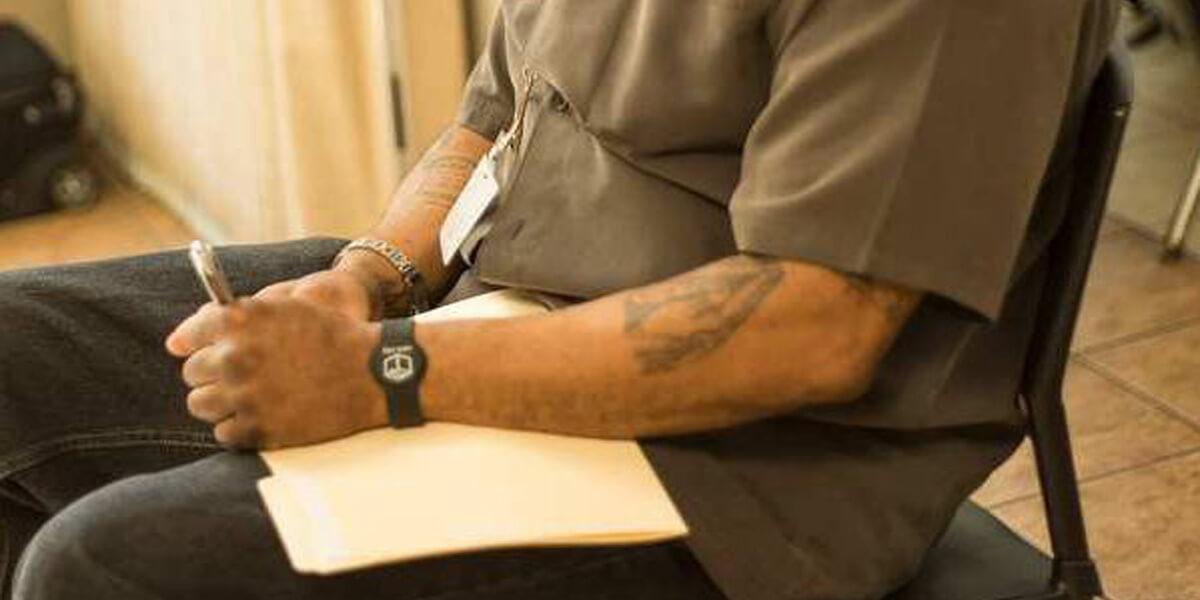

Six months into the pilot, Mini City distributed 500 NFC-enabled wristbands—similar to FitBits or Nike FuelBands—to expand its services to Atlanta’s homeless. Each wearable holds an identifier number given to homeless citizens when they begin the process of obtaining a government ID. Users unlock Mini City’s app by tapping the wristband on a tablet at Salvation Army and other nonprofits like ReStart Atlanta—allowing them to book shelter beds, find nearby employment and medical resources, and check the status of their ID applications.

With any tech solution to homelessness—especially one that involves wearables, there are privacy concerns. But Mini City says it’s doing its best to do its wristband program in a way that respects its users privacy: its devices are not GPS-enabled and store nothing but the user’s identifier number. “We absolutely never want to geolocate any homeless citizens, and we don’t store sensitive information,” co-founder India Hayes told me in a phone call. When logging in, the Mini City app relies on what its creators call a “security triple-check”—it asks security questions, requires a PIN number, and takes a photo of each user that it compares to photos on file. The Mini City app allows users to check the status of their ID applications, but it does not store the information they used to apply for an ID.

Also see: Homelessness and the digital divide: What it means and how to help

Motherboard asked Frederike Kaltheuner, who leads the data exploitation program at Privacy International, a London-based nonprofit that focuses on the right to privacy around the world, about any security concerns that could arise from the Mini City app and wearable. “In general, I’m not concerned having looked at this,” she told me. “It’s not a tracking device. It’s not a biometric system. It’s not a blockchain. There are many, many different ways you could do this that are much more privacy invasive.”

Still, any tech-based service comes with risk, Kaltheuner said: “If you have an ID number and a wristband with which you can log into services, there will be a database somewhere that has all of these data in it.”

She pointed to a 2017 study from the nonprofit research group Corporate Watch, which revealed that over a dozen U.K. charities serving the homeless had passed personal information to immigration enforcement teams for use in deportations. And even if they don’t do it willingly, there are some cases in which nonprofits and other groups can be legally compelled to share information with the government.

“Law enforcement can require agencies to hand over data under specific circumstances,” Kaltheuner explained. “Whenever you have a database, no matter what your intentions, there’s always the risk it can be accessed by other people . . . especially in the absence of data protection laws to prevent that.”

Mini City is not the first tech startup to use wearable technology to target the homeless population. Founded by Jonathan Kumar, Samaritan distributes Bluetooth-enabled “beacons” to homeless people in Seattle. Residents who want to help the local homeless population can download the Samaritan app to be alerted when they pass by someone wearing the beacon, read his or her story, and choose to donate money that can be redeemed at local restaurants and stores. But Mini City is unique in that it offers a simple solution that can ease a person’s path from homelessness to housing.

Though a nationwide—or even citywide—rollout is likely years away, Mini City plans to help more Atlantans obtain their IDs during its second pilot with Salvation Army later this year. Considering Georgia is one of seven states with strict voter ID laws, that work alone can help hundreds of homeless citizens make their voices heard in the November Midterms.

“The ID conversation is part of a bigger conversation about how to ensure equal access to political and economic power,” Tars of the NLCHP, told me in a phone call. “At the policy level, we need to devote our energy and resources to constructive solutions that can end homelessness, rather than push it out of public view, but it’s hard to advocate for yourself if you don’t have access to the ballot.”

While technology can make it easier to navigate the complex process of replacing a lost ID or accessing public services, it’s ultimately up to the government to ask why that process is so complicated in the first place, Tars said. “These sorts of things provide opportunity,” he said of the Mini City app and wearable. “We still have to change laws and policies—namely making IDs free for everybody and available without a permanent address—but technology is part of the solution.”

Kaltheuner of Privacy International pointed to an even more fundamental glitch in the system. “The fact that people need IDs in the first place to access services [is] the real privacy issue,” she said. “Why do you need two pieces of ID in order to get homeless benefits when everybody knows that homeless people do not have these documents?”

This story is part of a series of stories produced in partnership with VICE Media’s Motherboard.