KEY INSIGHTS

- The EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council meeting focuses on cyber threats from China but neglects to establish cybersecurity laws for minorities.

- Together, 45 percent of Black Americans, indigenous people and people of color (BIPOC) are slightly more likely to have their social media accounts hacked compared to 40 percent of white users.

- The Share the Mic project is fostering more dialogue for cyber equity in the workforce.

The recent inaugural meeting of the EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council brought many unanswered questions of government-issued cybertheft boundaries. The conference aimed to define the appropriate scope of state power to access and exploit data. National indecisiveness of cybersecurity boundaries and protocol adds to the digital gap for Black Americans.

“We say ‘if you torture the data, it will confess,’ and when you have the ability to surveil every action someone takes online, that’s a lot of data to use to prove a case against an individual or community or sow doubt or distrust,” Rachel Vrabec, Founder and CEO of Kanary, a personal data privacy company, told The Plug.

While the council meeting focused on online threats from China, the U.S. has yet to properly address cybersecurity issues domestically, especially issues that disproportionately impact communities of color. The U.S. has historically hurt Black Americans by collecting information on communities and organizations they perceive as a threat to power as seen through police brutality and social monitoring tracking apps.

Cointelpro is one of the more egregious illegal projects the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) set up to discredit American organizations such as feminist organizations and the Black power movement. Some Cointelpro tactics used were perjury, witness harassment, witness intimidation and withholding of exculpatory evidence.

Unfortunately, surveillance technology is now being used to take the same steps to discriminate against Black Americans. There is a recent pattern of police killings that expose the gulf in the perception of suspicion, crime, policing and justice between communities of color and white communities, according to a Government Technology report. The rise of new residents in gentrified neighborhoods and cyber-surveillance apps Nextdoor, Facebook community groups and Neighbors (a companion app to Amazon’s Ring) make it easier for people to call out suspicious behavior.

“I no longer feel safe being out at night or leaving my windows open due to fear of neighborhood social-media reports and 911 calls of “suspicious” people leading to police killings like Jefferson’s,” Reverend Kelly Brown, the Canon Theologian at the Washington National Cathedral, told Government Technology.

Lower-income and less-educated Americans generally experience more cyber threats and more lapses in online security.

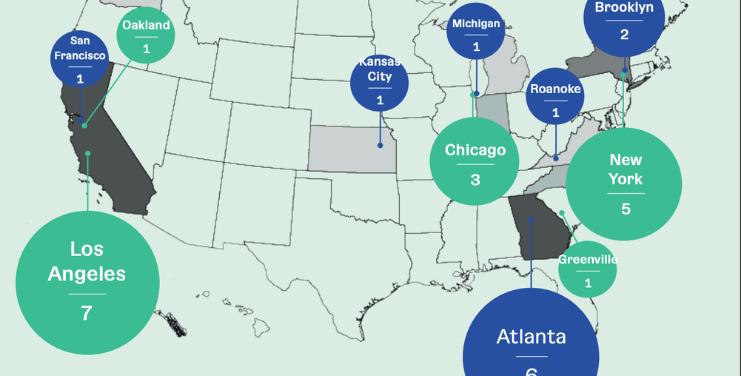

According to a 2021 Malwarebytes, Digitunity and Cybercrime Support Network survey, minority groups and those with lower incomes and lower education levels are more likely to fall victim to a cyberattack, and some groups are far more likely to encounter online threats.

Women are slightly more likely to experience malicious online behavior, with 79 percent of women reporting they have received text messages from unknown numbers that include potentially malicious links, compared to 73 percent of men. Forty-six percent of women reported having their social media accounts hacked compared to just 37 percent of men. Similarly, 45 percent of Black Americans, indigenous people and people of color (BIPOC) have had their social media accounts hacked, compared to 40 percent of while social media users.

Twenty-one percent of women and 23 percent of BIPOC respondents said they experienced “substantial” stress in dealing with suspicious online activity, compared with 17 percent of all respondents. Women also reported feeling less safe online than male users.

A few projects and groups are establishing new cyber protection measures.

Share The Mic was established to focus on the experiences of the top Black government cyber officials in the industry. Participants talk through their career paths and the difficulty of often working with few if any other, Black cyber professionals. They also plan to weigh in on significant issues in cybersecurity policy. In addition, the organization is also partly focused on improving cyber cooperation between government and industry.

Share The Mic aims to help create career paths for Black professionals and host conversations that go beyond one-day interactions. In past Share The Mic events, participants like Tayla Parker made Black Girls in Cyber from a conversation with Phil Reitinger, a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) worker. Parker took over Reitinger’s account. DHS is also changing the system for hiring cyber professionals.

“It’s a positive step forward that these conversations are being held more regularly, but it’s our opinion that this confusion will exist until comprehensive data privacy laws are passed and equality across accessibility is reached,” Ray Kimble, Founder & CEO at Kuma LLC, a global privacy and security consulting company, told The Plug.

The combined efforts of the government and advocates can cultivate more equity in the cyber workforce and user protections.

Sponsored Series: This reporting is made possible by the The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation

The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation is a private, nonpartisan foundation based in Kansas City, Mo., that seeks to build inclusive prosperity through a prepared workforce and entrepreneur-focused economic development. The Foundation uses its $3 billion in assets to change conditions, address root causes, and break down systemic barriers so that all people – regardless of race, gender, or geography – have the opportunity to achieve economic stability, mobility, and prosperity. For more information, visit www.kauffman.org and connect with us at www.twitter.com/kauffmanfdn and www.facebook.com/kauffmanfdn.