KEY INSIGHTS:

- Research firm Creative Investment Research launched an impact investing vehicle calling on the Federal Reserve to create a funding facility to reduce Black maternal mortality.

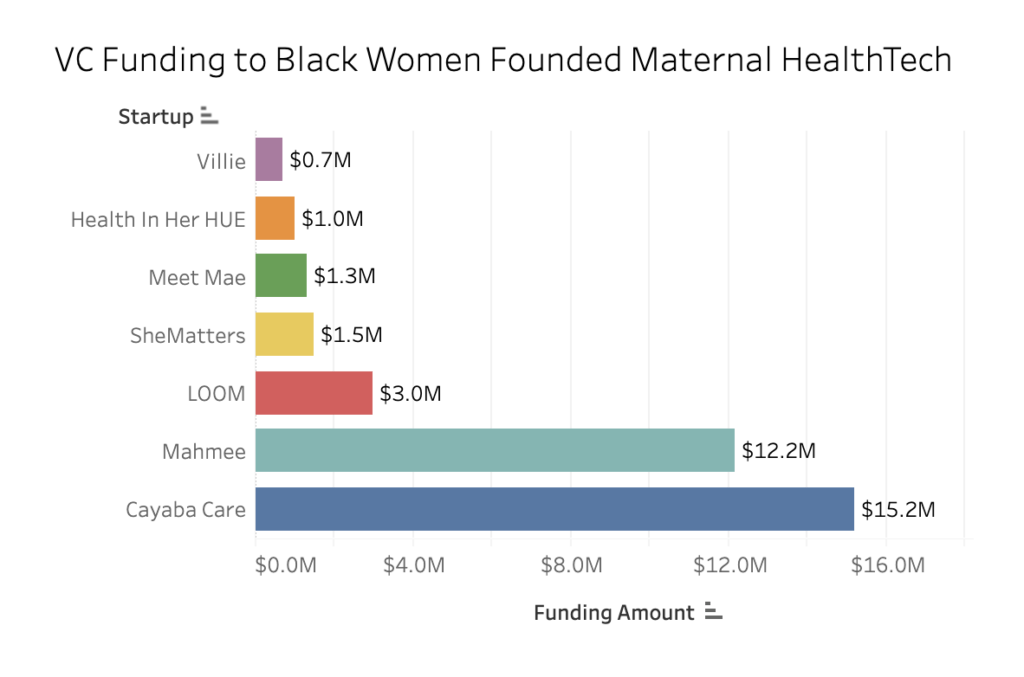

- Almost $35 million in venture capital funding has gone to Black women-founded maternal health startups, but the number is negligible compared to investment in overall healthcare technology.

- Maternal healthcare startups like Wolomi, which do not have VC backing, are underfunded but still leading the charge to improve the pregnancy journey for Black and brown birthing people.

Shalon Irving always wanted to be a mother. After years of trying to get pregnant, she became a mother at the age of 36, but just three weeks after giving birth to her daughter Soleil, she died from complications of high blood pressure.

After her death, Shalon’s best friend Bianca Pryor and her mother Wanda Irving founded the non-profit organization Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project.

Shalon was an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and held several professional degrees. Even equipped with an understanding of her elevated pregnancy risks, she did not get appropriate care after expressing to healthcare providers that she did not feel well during the postpartum period. Pryor, who was pregnant at the same time as her best friend, had a preterm labor herself.

“So here you have two Black women who were very educated and we really didn’t know what we were up against,” Pryor told The Plug.

Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women, according to the CDC, and these disparities persist even across educational levels. The mortality rate of Black women with a college degree is nearly twice that of white women with less than a high school diploma. But this harrowing statistic is not just a number — real people, families and communities are impacted by the shortcomings of the medical system.

Pryor and Irving are part of a network of Black female entrepreneurs who have taken power into their own hands by launching maternal health tech companies. Under their nonprofit, they launched Believe Her, an anonymous peer support app for Black birthing people and families. Users have a space to ask questions to help try to prevent more stories like Shalon’s. The CDC has launched a similar effort through its Hear Her campaign.

“If [Shalon] had been able to go into something like the Believe Her app then we’d be all in there, her mommy hive, saying, ‘Girl, no, you need to see a patient safety officer,’ and that helps widen the view of options because I think we find ourselves so limited that the only conversation to be had when you’re in pain is with your doctor,” Pryor said.

But funding still remains the most difficult part of alternative care platforms. Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project and the accompanying app have mainly been funded by Pryor and Irving along with a grant from the Ms. Foundation for Women.

A new crop of Black female venture capitalists are supporting Black maternal health startups, but founders say additional funding is needed to appropriately address this public health issue and more players need to step up to reduce the maternal mortality gap.

The funding landscape

Of the billions invested in United States-based healthcare technology to date, a minuscule percentage has been allocated to Black women founders who have launched Black maternal health tech companies.

“If white women were dying in childbirth at these elevated rates you better believe they would have all kinds of funding to deal with this issue,” William Michael Cunningham, the founder of Creative Investment Research, a research firm that has been working on influencing government policy around the maternal mortality gap, told The Plug.

The Plug has identified at least $34.9 million in VC funding to seven startups working to reduce Black maternal mortality: Health in Her HUE, Meet Mae, LOOM, Cayaba Care, Villie, SheMatters, and Mahmee. Serena Williams is an investor in Mahmee following her own experience of almost dying after giving birth.

Rhia Ventures, which funds sexual, reproductive and maternal health, and Seae Ventures, which invests in early-stage healthcare tech founded by women and people of color, are some of the investors to fund multiple of these startups. The CEO of Rhia Ventures, Erika Seth Davies, is one of several Black women VCs leading the charge to fund this sector.

Black women at the helm are underfunded

Like Pryor and Irving, there are several other Black women founders working in maternal health who have not turned to or were unable to secure venture capital.

Layo George, the founder of Wolomi, an online pregnancy community for women of color, has a background as a labor and delivery nurse. Since launching in 2019, her efforts have been focused on building the platform and not as much on fundraising. Wolomi is bootstrapped and recently received $100,000 from the Google For Startups Black Founders Fund.

“A lot of us are moms and oftentimes we don’t have family members who have done this before, so we are really honestly at the mercy of organizations,” George told The Plug.

George started working on Wolomi while getting a master’s in healthcare administration and learning about the Black maternal mortality rate. She was also pregnant.

“I knew that the people who were making decisions about us didn’t look like us and if we wanted better healthcare outcomes, we needed people in the C-suite that understood what it is like to experience the healthcare system in this skin color,” George said, explaining it is often administrators making healthcare decisions, not doctors and nurses.

The healthcare professionals who are interfacing directly with patients don’t always get it right. That is why founder Kimberly Seals Allers created Irth, an app for rating and reviewing hospitals, OB-GYNs, and other pre-and post-natal care providers.

Allers, who Pryor regards as “one of the OGS in the game,” has raised at least $850,000 in grant funding, including a grant from the Goldman Sachs Group, as part of its One Million Black Women initiative.

Black women founders understand what the community needs, the only deterrent is money, and the irony is maternal health tech founders have to compete against each other for funding from the VCs who have taken notice of the crisis, George said.

Like other maternal health platforms, Wolomi’s main customers bringing in revenue are insurance companies who seek to partner with platforms that have an understanding of Black and brown birthing people.

“That’s where the real magic happens because now it becomes preventative and becomes a part of the discourse. Your doctors are now able to talk about it and provide you with a real resource,” Believe Her founder Pryor said of startups partnering with insurance carriers to embed the app in the pregnancy journey. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota recently announced a collaboration that will provide no-cost access to Health In Her HUE.

Coming full circle, the founder of Health in Her HUE, Ashlee Wisdom, shared with Irving that it was her daughter Shalon’s story that inspired the creation of the digital platform.

Policy efforts are moving slowly

Founders and venture capitalists cannot solve this public health crisis alone — government entities need to play an active role.

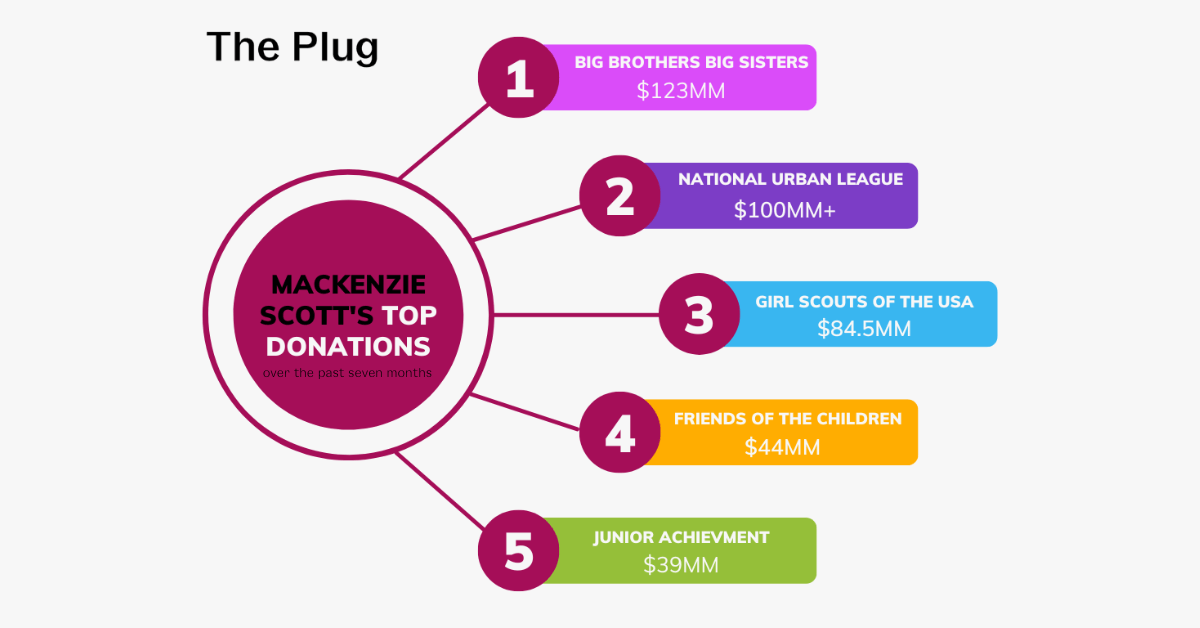

Creative Investment Research thinks the Federal Reserve should contribute to funding efforts to address this problem.

“The Federal Reserve created a number of facilities to finance majority-white big financial institutions,” Cunningham said, pointing to programs like the Municipal Liquidity Facility and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility. The U.S. government has also been the financial launchpad for big tech companies like Google.

“I want them to create another liquidity facility designed to provide liquidity for companies that are addressing the issue of Black maternal mortality. It’s not rocket science. We just use the stuff which is out there,” he said.

Through the impact investing vehicle Maternal Mortality Reparation Facility for Black Women, Created Investment Research has crafted an investment agreement for the Fed to finance individuals and institutions that can address social determinants the firm has identified as contributing to Black maternal mortality: access to nutrition, transportation and healthcare.

“The bottom line is that technology allows us to address the three main factors that are leading to elevated rates of Black women dying in childbirth,” Cunningham said.

The reparation facility has gained some traction since the firm announced the proposal in July 2021. The Fed assigned this issue to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which released a maternal health report in December 2021. It highlighted the need for greater investment in areas including home visiting and doulas and enhancing partnerships among community-based organizations, the private sector and start-ups.

But Cunningham said the report falls short by not including Black women who are already leading the charge and are all too often not invited to the table. Instead, it was written in collaboration with NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing.

“We have the lived experience. Come to us if you’re trying to serve Black women and bring down the maternal mortality rate. Talk to some of the people who understand how it impacts communities and who have the answers for you,” Wanda Irving, co-founder of Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project, told The Plug. “Fund some organizations like us with the community’s best interests at heart and give us a chance to show that we can make a difference.”

Of note, one of the proposed public policy solutions in the report is the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021, which Irving testified in support of to Congress. Sponsored by Rep. Lauren Underwood, who was a classmate of Shalon’s at Johns Hopkins University, and Rep. Alma Adams, the Momnibus Act included 12 bills addressing maternal mortality. However, the bill never got past committee.

“Shalon’s story has served in the Black maternal health space as that story to awaken the beast, so to speak, in Congress and get them to hear that this is truly a horrifying issue,” Pryor said, noting that Momnibus would support health tech apps and startups.

Rep. Underwood recently called for the immediate passage of the act in response to a new report released by the Government Accountability Office that found the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to an increase in maternal deaths, especially among Black and Hispanic communities.

“We have had the opportunity in the past to be before politicians and to talk about Shalon’s story and what’s necessary as we move forward. There were a lot of tears, a lot of pearl-clutching and promises of, ‘We’ll do better,’ and nothing has changed in that arena,” Irving said.

Moving forward, Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project’s focus is to partner with institutions like the Sutter Institute for Medical Research, Morehouse School of Medicine and John Hopkins Center for Health Equity to amplify a collective voice before policymakers.

Wolomi founder Layo George recognizes policy efforts are critical, but transforming the systemic racism embedded in the U.S. healthcare system is going to take time.

“If we wait for all the resistance, so many lives will be lost. We cannot wait and be at the mercy of if the healthcare system decides it is going to get its act together,” George said.