On a typical weekday, New York City subway stations can expect an estimated 5.5 million riders clamoring on their platforms in a rush to get to work across any of the five boroughs. Boasting the country’s largest mass transit system, New York virtually came to a screeching halt as COVID-19 forced most commuters indoors during the March shelter-in-place shutdown. Recovery, now six months after countries across the globe announced stay-at-home orders, has been faint.

The city has seen ridership plunge by as much as 90 percent, along with its revenue, thrusting the agency into a tailspin of a budget crisis. Faced with both fraught public health and economic climate, those bearing the worst of the world’s woes are those still required to leave their homes to earn a paycheck. From grocery store workers to airport maintenance crews and home health care workers, a lacking transit system means a longer, crowded, and unreliable route to work.

Where Uber and Lyft have seen drastic declines in ridership and revenue, Dollaride is finding its footing in communities traditionally underserved by transit, filing in the gap of the last mile and emerging to be a power player in the future of transportation in urban cities.

A Future (And Past) Driven by Immigrants

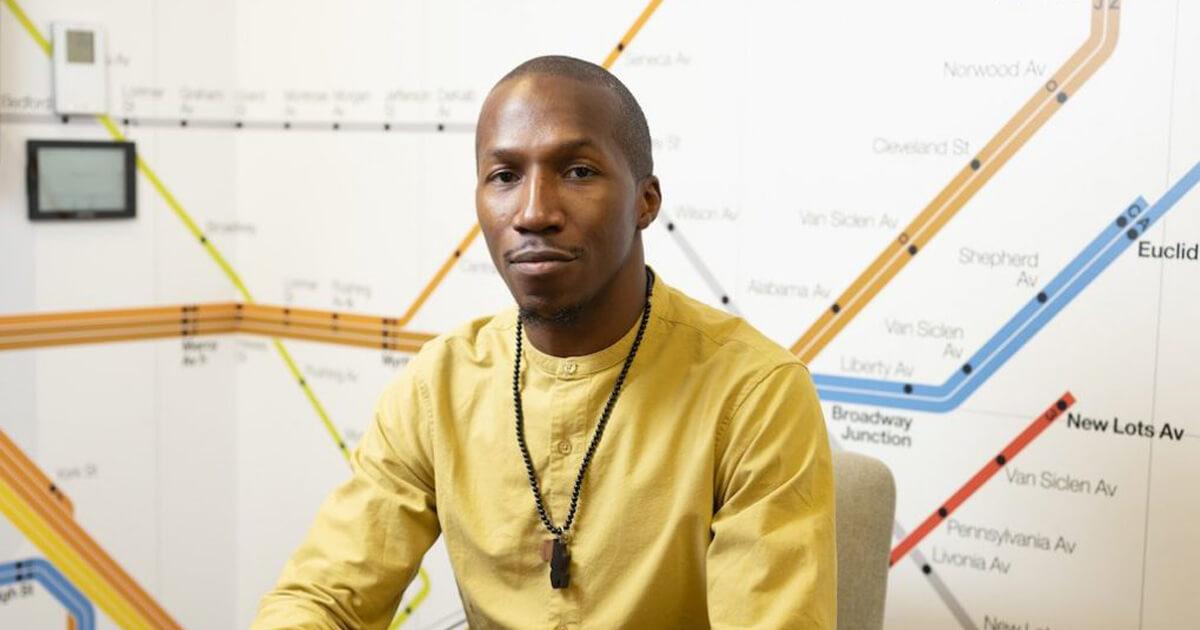

Launched by Sulaiman Sanni in early 2017, Dollaride is somewhat of an evolution of the infamous dollar van staples that have defined informal transit systems within communities of color traditionally underserved by public buses or trains. Since the 1980s, New York’s Caribbean and Asian immigrant communities have operated shadow transit services that for $1 to $2 per ride could get you home to the nearest train.

It was the original ride share service that operated without permission until 1994 when the Department of Transit and the Taxi and Limousine Commission began providing licenses for commuter van operators and formal recognition to drivers picking up the slack where transit had not reached certain communities.

Sanni’s uncle went from driving the dollar van in the ’80s to eventually operating a full fleet of vans among the 2,000 licensed vans operating in the city today. I grew up around the game, watching them work, and even working with them, said Sanni, founder and CEO of Dollaride. Ultimately I got the idea [for the company] from living in Jamaica, Queens‚ transit desert‚ where hundreds of thousands of people use dollar vans to go to work and school.

One summer, Sanni said he even did research for one of his uncles on the future of transit and how apps like Uber and Lyft have impacted the outer boroughs. And that is when the idea for Dollaride was sparked after he’d discovered that 90 percent of the people who take dollar vans have smartphones, credit cards, and use payment apps like Venmo and Square. This is the second venture for Sanni, who sold his first company, WeDidIt, a fundraising platform for nonprofits, in June of last year to Allegiance Fundraising Group.

Finding a Path Forward Amid the Chaos

New York City transit wasn’t the only mass transit system that took a hit during the early days of the pandemic. Ridership for dollar vans also saw a significant drop in ridership. We were facilitating upwards of almost 120,000 riders per day through the Dollaride app out of the nearly 300,000 people who use a dollar van each day, said Sanni. But once COVID-19 hit, those numbers fell flat to nearly zero.

Sanni noticed that people who are riding the most are people who do shift work, or the graveyard shift, so they’re leaving home super early in the morning or returning late at night when transit options are significantly scarce. Since mid-May, New York’s transit authority shut down subway service between the hours of 1 a.m. and 5 a.m, leaving employees traveling during those times stranded or stuck with slow and overcrowded buses, a challenge that is sure to get worse for workers as the winter months ensue.

Forced to seek alternative revenue streams to tread the tide, Sanni established partnerships with corporate companies and government agencies to create shuttle options and new routes for employees, a strategy that Uber and Lyft bypassed when launching into new markets during their early days. This is the process that makes it highly profitable, said Sanni, who said that the riders for these routes are all shift or wage workers.

One such contract is with the GatewayJFK Business Improvement District, a 215-acre area adjacent to JFK Airport in Queens, New York, with over 600 businesses in the air cargo and e-commerce, logistics, and trucking industries. Pre-COVID-19, the area employed over 8,000 workers hailing from neighborhoods like Jackson Heights, Flushing, Woodside, and Jamaica, Queens. I saw Su speaking on a panel at an Urban Planning conference and I was very impressed with Dollaride, said Scott Grimm-Lyon, executive director of GatewayJFK. We started speaking about working together shortly after. GatewayJFK had been exploring shuttle service options because we knew there was a huge need in the neighborhood.

Employees come from across the region via the subway, spending about 40 minutes to an hour each way on the train. But despite the high level of employment in the area, leaders say it’s not well connected to the NYC Subway system, or the Long Island Rail Road. One of the most important factors for us was finding something that gave us a level of service that we felt was going to be regular, consistent, and reliable for our employees, said Grimm-Lyon, According to Grimm-Lyon, GatewayJFK inked a $50,000 per year subcontractor deal with Dollaride under the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority grant, which will provide coverage for two vehicles along with a supplemental contract for a third vehicle that will be paid directly by GatewayJFK.

The grant will provide subsidized rides for commuters and make the case for a permanent and profitable route for drivers. The contract also includes costs for providing marketing services of the current Shuttle Service, which will be handled by Dollaride. We plan to work with them for the foreseeable future. Once we can get a level of ridership of approximately 150 passengers a day, we plan to negotiate the next phase of the plan which is expanding the frequency of service, attracting residents who want to commute in the opposite direction as our employees, and attracting new drivers to the route. Ideally, the Dollaride app will be a primary tool that our employees use to help them on their commute for decades, said Grimm-Lyon.

Beyond a New York State of Mind

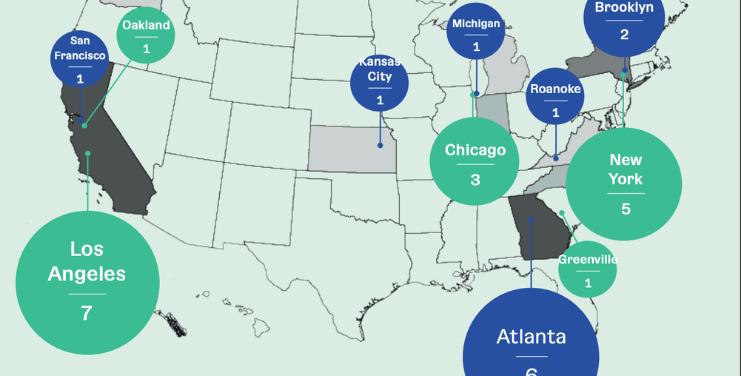

The dollar van transit system is not exclusive to the Big Apple. These informal and formal transportation economies exist all over the world in densely populated cities where access to adequate public transit is lacking in communities typified by lower incomes, urban sprawl, and extreme disinvestment. Sanni’s 12-month milestone includes expanding into markets like New Jersey, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and Miami next year by implementing the brand ambassador model he and his team of nine employees have been able to deploy successfully in New York City.

Sanni got his first cohort of over 200 drivers onto the platform through the use of local brand ambassadors who help share the technology with (often) older drivers and get them completely hooked up on the system. Dollaride takes a commission on any ride that’s over $2. The commission structure works out to be between 20 percent up to 33 percent depending on the route. Like many Black tech founders, Sanni’s had to do more with less. Today, Sanni has raised $385,000 in funding for Dollaride thus far from a mix of angel investors (including one of his uncles), grants, and pitch competitions.

As the company looks to expand into new markets, they’re doing so without the type of capital backing inherent for Uber and Lyft, who were able to raise billions of dollars very early and set up shop in cities quickly. Instead, the approach is much leaner and predicated on how they solve for the risk of being in markets without an immediate office where engendering trust with drivers and communities is paramount. We assume the pandemic will still be alive and active. Dollaride has to be agile as we operate in this new normal, said Sanni. The way we expand will be more data-focused versus operationally heavy.