KEY INSIGHTS:

- Winston-Salem State University is the only HBCU with an astrobotany lab.

- The research is conducted in partnership with NASA.

- The experiments are informing future technologies to help humans in space or on Earth, and helping diversify a lucrative field.

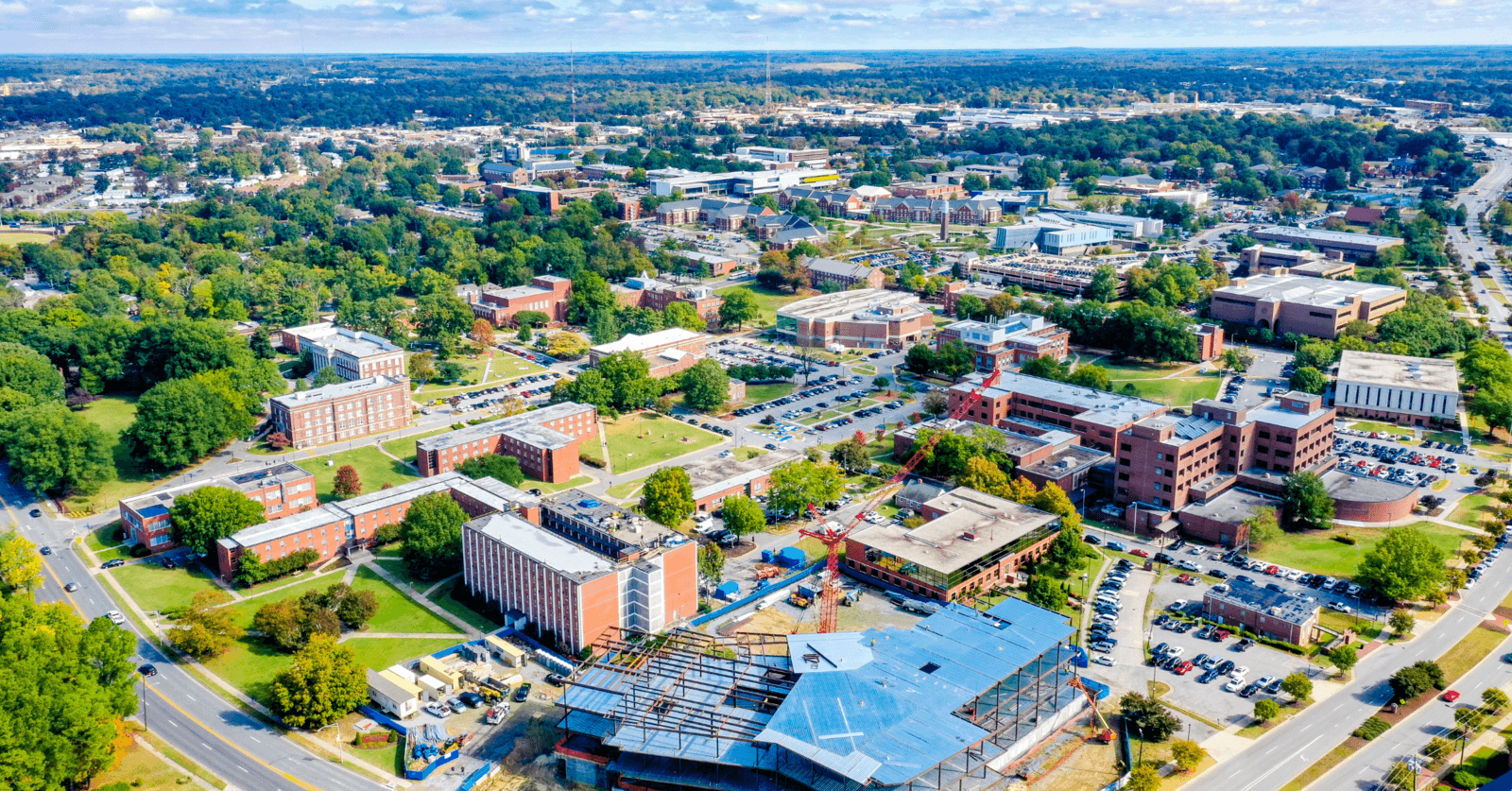

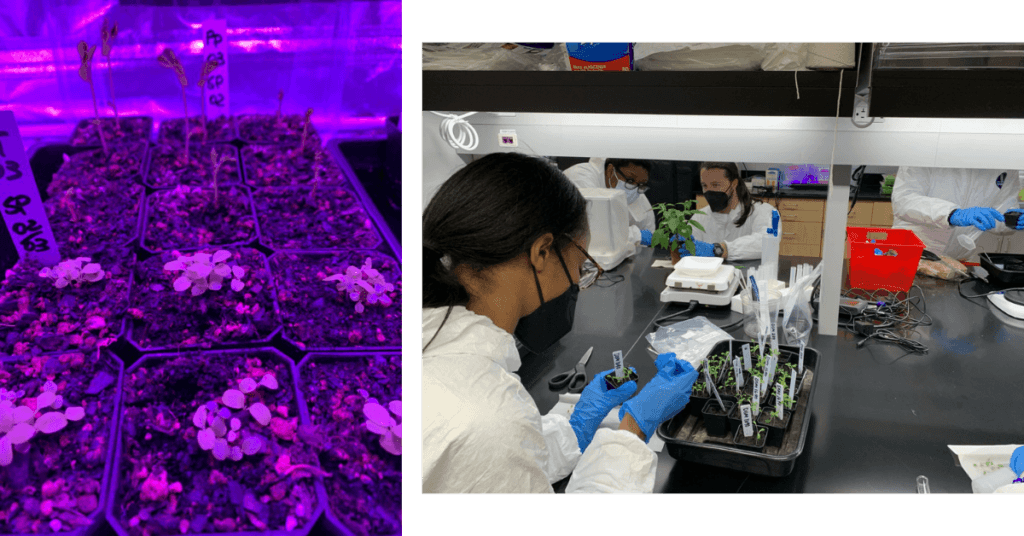

In a lab at Winston-Salem State University filled with purple grow lights and refrigerator-sized chambers, students meticulously grow bok choy, peppers, lettuce, tomatoes and more. But these are not typical fruits and vegetables — they are all being designed to survive in outer space. This research is part of a field called astrobotany, and WSSU is the only HBCU with a lab dedicated to it.

“Astrobotany is us trying to figure out agriculture elsewhere in an environment that is, pun intended, completely alien to plants,” Rafael Loureiro, assistant professor of botany at WSSU and head of the astrobotany lab, told The Plug.

At Loureiro’s lab, students grow plants in regolith, a simulated Martian or lunar soil that has never been exposed to the types of microbes that make the nutrients in Earth’s soil accessible to plants. Some plants are also subjected to random positioning machines to mimic lunar gravity.

The goal of the research is to figure out how to get crops to grow and produce in stressful environments, which they have successfully done with a few plants, though the subsequent taste tests have had mixed results.

“Those plants are going to be very low in vitamins, a lot of the stress is going to show in taste,” Loureiro said. “But some of the ones that we already got the hang of, they taste very, very normal. I would say not better, but normal and we’re okay with normal.”

But though taste might seem like a small factor, it is a nod to the fact that outcomes of this research will lead to people being fed in places where traditional agricultural practices may not work.

“Every single technology that we develop here is 100 percent transferable anywhere,” Loureiro explained. “If you unlock the code on how to grow plants in extremely stressful situations, you can do that anywhere. You can do that in extremely arid places in the Middle East. You can do it in Africa, you can do it anywhere.”

This crop production is also as important, if not more, as rockets for space exploration and the possibility of humans living on another planet. As Loureiro pointed out, civilizations as we know them only began forming on Earth when people tamed plants and animals.

For Loureiro, it was important to bring this research specifically to an HBCU. When he joined WSSU in 2018, he wanted to be able to offer his students the opportunities that he did not have growing up in Brazil fascinated with space but no way to pursue it.

“I know how it feels, it is frustrating for you to want to be in a field and you just do not have the means to get to that field,” Loureiro said.

Eventually, he combined his love of space with his training in plant physiology. By the time he chose to come to WSSU, his connections with NASA’s Kennedy Space Center helped lead to the establishment of the astrobotany lab.

In 2019, NASA began officially partnering with WSSU on this research. Undergraduate students can receive up to five-figure grants from the agency for their research, have current NASA employees as mentors and get access to internship opportunities.

The NASA-WSSU partnership is particularly important because Black people are sorely underrepresented in the agency. In 2021, 10.9 percent of the NASA workforce was Black, yet only 2.3 percent occupied senior scientific and professional positions, and 1.1 percent were in senior-level positions.

“[Space is a discipline] in which broadening participation, in general, has decreased,” Erin Lynch, recent Associate Provost for Research and Innovation and Dean of the Graduate School at WSSU, told The Plug about the school’s relationship with NASA. “I’ll be honest, I don’t know if I have seen a Black astronaut so visually presented as when I was in elementary school [with Mae Jemison].”

Loureiro’s student researchers have gone on to pursue PhDs with offers from NASA already lined up once they finish, go to medical school, become master growers at horticulture companies and more.

But ultimately, astrobotany is not about outer space or plants, despite what it sounds like — it is about humanity, Loureiro believes.

“All of this that was designed for space will most likely be supplementing agriculture in the future here on Earth,” he said. “We’re not just doing it for space, we’re doing it for humanity in the grand scheme of things.”