The Civil Rights act of 1964 passed just a year after my mother was born. Unlike my grandfather and grandmother before her, this law would provide a legal tool for my mother and other racial minorities to use as a defense in response to discriminatory practices and behaviors by existing and future employers.

Though not a catch-all for gross inequality, it was a small start amid the backdrop of racial injustice and lack of economic opportunity for African Americans in our country’s storied racial history. Also known as Title VII, the law, amended in 1972, has since worked to prohibit discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, and religion, as well as the retaliation against employees who might seek to exercise their rights against an employer.

Since the law’s inception, enforcement and compliance have been carried out by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission who would later give us public access to understanding how various demographic and gender groups are represented in various industries and job roles across the country. But it didn’t give us what we needed most: a measure in which to hold companies accountable for not hiring or promoting racial minorities within the workplace.

Key Takeaways

- Private companies with more than 100 employees are required to self-report information about pay, gender, and racial representation across their companies.

-

- Very little specific data attributed to companies is made publicly available. Instead, diversity reports remain voluntary.

- The Plug found that out of the 190+ companies making statements about racial justice, less than 45% have published diversity reports and audits.

Specificity Matters

Employers with more than 100 employees, save for state and federal contractors, are required to submit their data to the EEOC every year. However, the data is significantly limited, protecting companies’ confidentiality by not naming them specifically, but allowing the general public to search for aggregate industry information.

This is useful when accounting for high-level labor statistics and representation as well as workforce unemployment. It’s not so useful, however, in understanding where advantages and disadvantages in the workforce for marginalized groups exist on a granular level and at which companies. Thus, accountability is tempered, hiding behind datasets that merely skim the surface of accountability.

Making the First Move to Map The Data

It wasn’t until 2013 when tech giants Google, Yahoo, and Facebook shared their employee data publicly for the first time in their self-reported annual diversity statistics, that we got a lens into how the data broke down in the private sector.

Through the years, more tech companies have been adopting the practice to provide transparency in their employee data. But without the requirement to release this information, measuring inequality within private companies and organizations continues to be more of a challenge without the data to back up the inquiry.

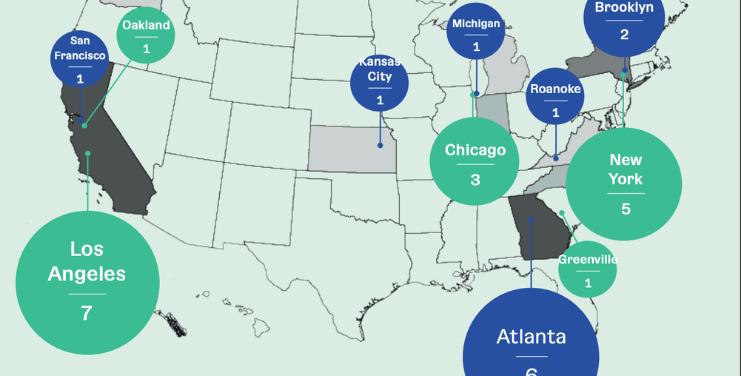

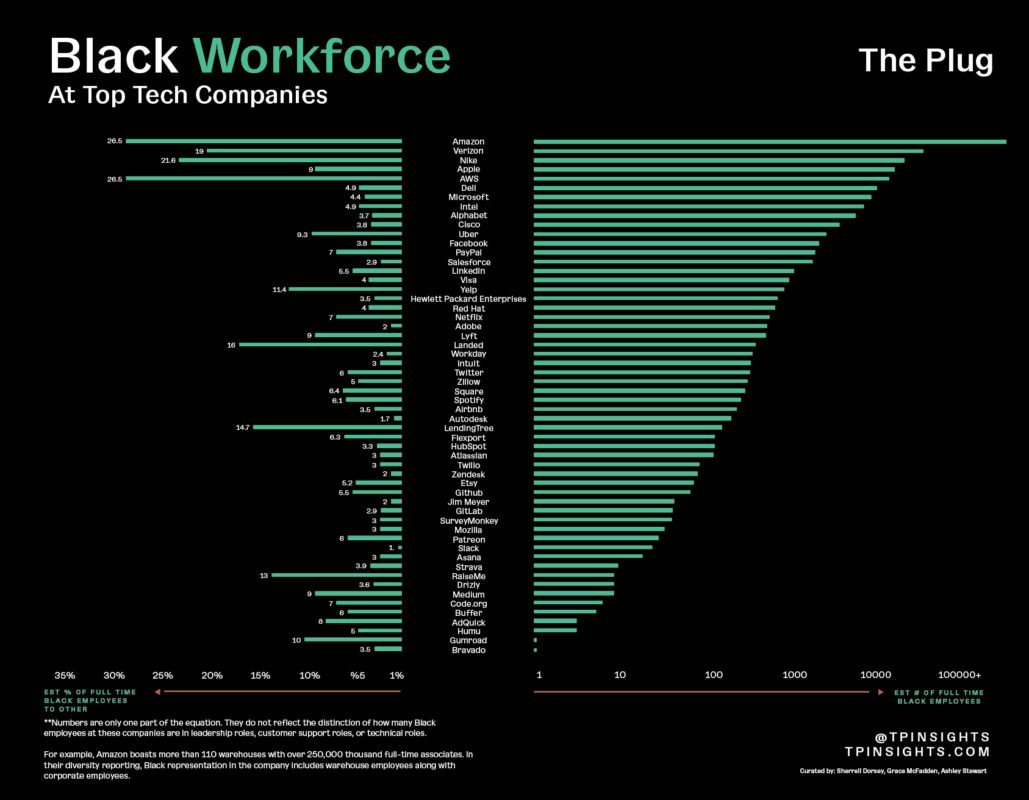

This reality also affects the current work of my team on mapping against tech companies that have provided statements in response to speaking out against racism, racial injustice, police brutality, or in support of Black Lives Matter. The following graphs are indicative of our first take at analyzing over 190 companies within our database.

We first sought out the company’s most recently published diversity report. For those that published corporate diversity numbers publicly, < 45% of our list, we added the published percentage of overall Black employees represented. Numbers are only one part of the equation. They do not reflect the distinction of how many Black employees at these companies are in leadership roles, customer support roles, or technical roles.

Of the 194 companies we tracked, less than 45% had publicly available data on the diversity of their company. We have followed up with several companies who have shared their statements with our team to also share their internal diversity numbers. We are finding that some companies do not currently collect or audit this data. Some do not collect granular information based on leadership or technical role representation. Some have promised to begin collecting this data. Others have not yet responded to our request for more information.

If the EEOC requires this reporting, either these companies are not in compliance or we can assume that the unwillingness to share is less about lack of auditing and more so about protecting themselves from public criticism.

A Future of Transparency? Likely Not

We’re slated to face an ongoing lack of reporting and transparency, and potentially inequity in hiring over the next year as ease of EEOC restrictions take root and unemployment continues to rear its ugly head. The EEOC publicly released a statement on the delay in 2019 data survey results on employee reporting, stating:

In light of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) public health emergency, and consistent with delays in Federal reporting requirements across the government and other actions taken to relieve employers of unnecessary burdens during this crisis, the Commission is delaying the anticipated opening of the 2019 EEO-1 Component 1 and the 2020 EEO-3 and EEO-5 Data Collections to a time when the agency anticipates that filers will have resumed more normal operations.

Considering that this data collection will be delayed until 2021, this window removes one of the very few accountability measures of private employers and could further impact the economic opportunities of minority employees.

While companies could, of course, turn the tide and join in on self-reporting through their own audits, we’re unlikely to see this become a priority within the next year without significant support from leaders or internal advocacy from employees.