KEY INSIGHTS?

- New forms of immersive technology circumvent how Black history is taught in schools.

- Digital archiving presents new ways of preserving Black history.

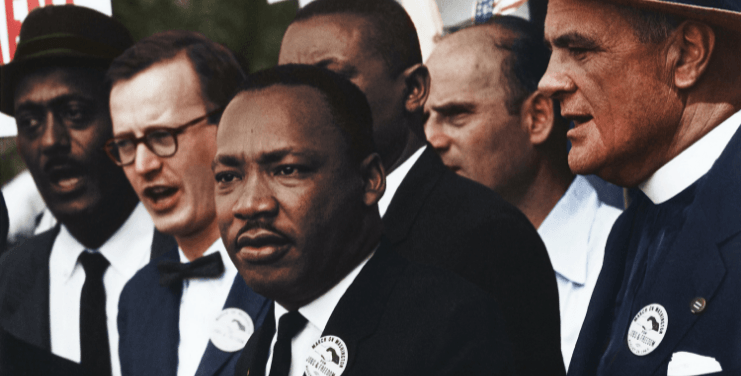

- The preservation of Black history is not limited to the 18th and 19th centuries, and technology is capturing today’s racial justice movements.

Despite going to one of the most prestigious schools in New York City, Idris Brewster still received an incomplete version of American history.

“I didn’t have a Black teacher until the 11th grade, and the curriculum wasn’t covering Black history, Brewster told The Plug.

Now an adult, Brewster co-founded Movers & Shakers, an ed-tech nonprofit that utilizes augmented reality to allow anyone to explore the histories of the people so often left out of classroom textbooks.

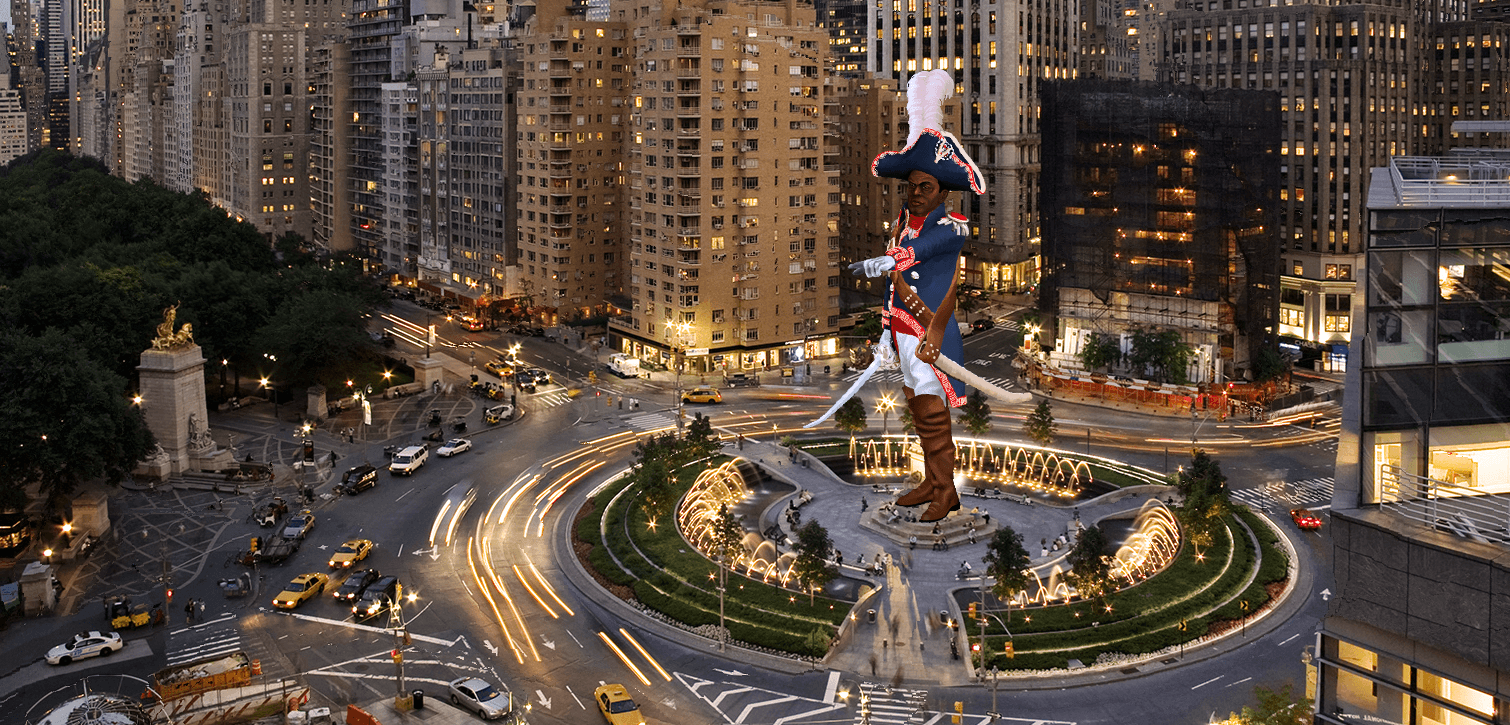

Founded in the wake of the deadly Unite the Right rally, Movers & Shakers initially set out to join the chorus of voices calling for the removal of statues celebrating settler colonialism and white supremacy. After former New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio refused to remove the Christopher Columbus statue from Columbus Circle, the group began to think of using immersive technology to circumvent future roadblocks.

Kinfolk, one of Movers & Shakers’ core products, seeks to deconstruct the euro-centric history taught in schools and uplifted in our nation’s monuments by featuring a catalog of augmented reality-enabled monuments depicting women, people of color, and LGBTQIA+ icons.

“With this technology, we can empower communities and not just raise the power of a central community but also lower the barrier of entry to be able to create monuments,” Brewster said.

History curriculums in America have been a hotly contested issue that has gained renewed attention recently as states across the country pass legislation that limits how educators can discuss race, gender, and systemic inequality.

A 2018 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center argued we might need more education on 17th-century American history, not less of it. The report found that only eight percent of high school seniors surveyed could identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, but close to 70 percent did not know that it took a constitutional amendment to end slavery formally.

As technology becomes more advanced, organizers and educators have utilized it to preserve history in new and immersive ways. When Gabrielle Foreman took her graduate students on a trip to Harpers Ferry a few years ago, they used a Facebook network plug-in to visually see how historical Black activists were involved in the post-Civil War Colored Conventions. Foreman, her colleagues and students realized that they could use similar technologies to bring the early history of Black organizing to digital life.

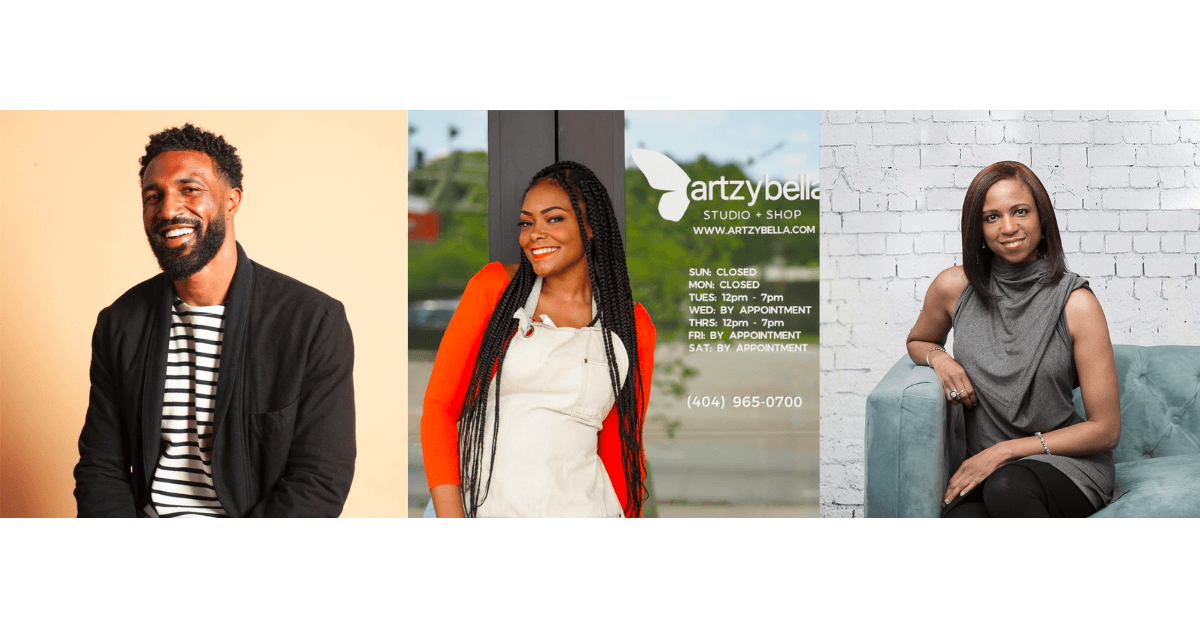

Shortly after the trip, The Center for Black Digital Research, also known as #DigBlk, was born. #DigBlk engages the public in preserving Black organizing histories through digital technologies and programs like the Colored Conventions Project.

The Colored Conventions were Black-led public meetings held throughout the antebellum period and 30 years beyond the Civil War. Both free-born and formerly enslaved Black people came together to organize around education, labor and legal issues. The delegates to these meetings included the most prominent church leaders, writers, educators, and entrepreneurs.

The contents of these conventions are not widely preserved, taught, or distributed, and the Colored Conventions Project seeks to fill that gap and curate digital exhibitions that highlight its significance.

“We realized very early on that this couldn’t be an academic project and that we needed community partners that had deep relationships,” Foreman told The Plug.

Knowing that the Black church has historically been a sacred place for fostering relationships, Foreman recruited Denise Burgher. The latter is now a Colored Conventions Project Fellow and Ph.D. student at the University of Delaware. Burgher coordinated with the national African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) to transcribe their historical records upon her arrival.

“We had historic churches where the Colored Conventions took place and had people transcribe those records,” Burgher told The Plug.

This initial effort turned into an annual transcribe-a-thon held on Frederick Douglass’ chosen birthday each year. Foreman and Burgher invite thousands of people from around the world to transcribe archives of Black American activists. This year, they are focusing on the participation of women in the Colored Conventions Movement, inviting transcribers to parse records that have already been transcribed to look for mentions of women, Burgher said.

Douglass Day, the name of the transcribe-a-thon, was a holiday created by Mary Church Terrell to ensure that Frederick Douglass’ legacy stayed intact. For years, the day was celebrated in schools, particularly in places like Washington D.C., before phasing out in the early 1900s. According to Foreman, the transcribe-a-thon is an opportunity not just to celebrate Black history but collectively do the work in preserving it.

This preservation of Black history is not limited to 18th or 19th-century Black history. Culture makers have always sought to sustain and share Black history – and the increasing integration of art and technology has blurred the lines between archivist and artist..

LaJune McMillian, a new media artist and educator, launched The Black Movement Library (BML) in 2018 as a space for activists and artists to archive Black existence in real-time. Through live performances, digital experiences, workshops, and conversations, McMillian uses motion capture data to explore how Black people move.

“I wanted to understand what it means to archive our stories, lives, histories, and what it means for space both digital and physical to encompass all of these things,” McMillian told The Plug.

Last summer, McMillian took the Black Movement Library to the steps of the Brooklyn Public Library to host a series of public outdoor performances, featuring underrepresented artists and bringing to life the movements and stories of Black people without the exploitation, extraction and commodification that is common in the tech space.

Through this process, McMillian hopes to uncover other ancestral ways of being that give us a better sense of how to move in a white patriarchal world. “I’m a believer that our ancestors have left so much for us, so many technologies for us, and we just have to tap in,” they said.