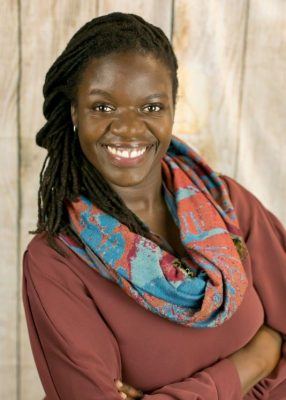

When educator Tiffany Shumate relocated to Oakland from the East Coast four years ago, she found that the luster and resources of nearby Silicon Valley didn’t cross the bridge to her community, even though she’d heard Big Tech companies issue platitudes about wanting to be involved.

“I ended up in East Oakland and being like, we are literally surrounded by wealth. And yet the schools, students, this talent has no access to it,” she said.

Shumate became determined to connect the dots. She created partnerships with EA Sports and Pandora that brought apprenticeships to students at Roots International Middle School where she worked. She went on to assume leadership positions with nonprofits Black Girls CODE, AI4ALL, and her newly appointed role as executive director of Hack the Hood, all organizations that provide resources and exposure to STEM careers for underserved communities. Hack the Hood has taught over 1,000 students and young adults to design functional websites for local small business owners since its founding in 2013.

This kind of concerted effort is how today’s majority-minority cities can become the tech hubs of the future. As we continue our series on the Future of Work, we focus on the emerging in-demand tech skills, and the ways cities can create ecosystems for the talent that will occupy the emerging high-growth jobs.

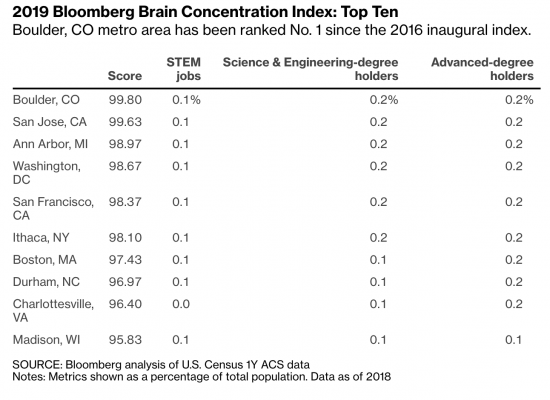

Bloomberg’s “Brain Concentration Index,” which tracks the highest-density areas of STEM workers, ranked America’s top tech hubs as Boulder, Colorado; San Jose; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Washington, D.C.; and San Francisco. Though rapidly changing, D.C. is the only city in the top 10 where minority residents comprise the majority of the population is the majority. This has the potential to change.

Now that COVID-19 has caused a shift to remote work that’s led Big Tech companies like Facebook and Twitter to allow employees to work from home indefinitely, Black professionals looking to break in may no longer have to move to inhospitable tech hubs such as San Francisco and Boston, known for their lack of diversity and unaffordable housing markets.

Hyma Moore, VP of External Affairs for economic development organization Greater New Orleans, Inc., says New Orleans is seizing opportunity in the remote work landscape to capitalize on the fact that its culture is much more attractive than the typical tech hub.

“What we realize is a lot of the Black people in tech just do not enjoy being in San Francisco or Seattle,” he said. “And so we’re doing a big recruitment campaign—for people who went to high school or college here, had their first tech job—it’s called ‘Welcome home.’ If you’re going to work from home, you might as well do it from here. Don’t be miserable.”

With the right support and infrastructure, many cities that are already diverse can be empowered to revamp this country’s idea of where tech equity can thrive.

THE TECH SKILLS OF THE FUTURE

STEM careers are in high demand, and the rate of growth is accelerating. In an unpredictable chain of events, the pandemic has brought many of the skills and positions projected as critical to the Future or Work to the forefront faster than imagined.

“Right now it’s predicted that automation is going to eliminate up to a quarter of our jobs. And right now we know who is concentrated in those jobs, right? It’s usually women, Black and brown people, folks from low-income environments,” explained Shumate. “COVID has already exacerbated that. The Future of Work is here. Automation is here.”

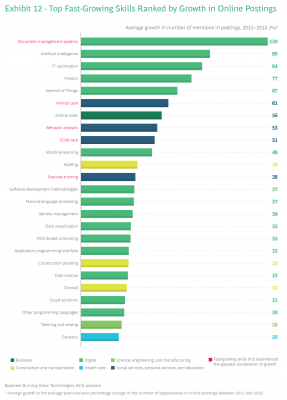

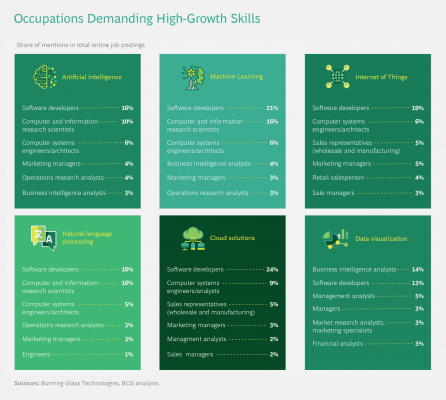

Analytics software company Burning Glass looks to job openings to inform its perspective on the economy. Many agencies rely on labor indicators such as unemployment insurance claims, which take a snapshot of the present; job postings provide an indication of how employers see the future. Burning Glass found that artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, cloud solutions, machine learning, and fintech made up 70 percent of the fastest growing skills.

Burning Glass dug deeper into the occupations asking for these high-growth skills and found demand from retail, marketing, sales, and other roles typically not categorized as tech. This implies the tech skills of the future will allow workers to apply their talents to a variety of fields that can provide fulfilling careers and livable wages.

Creating New Diverse Tech Hubs for Future of Work

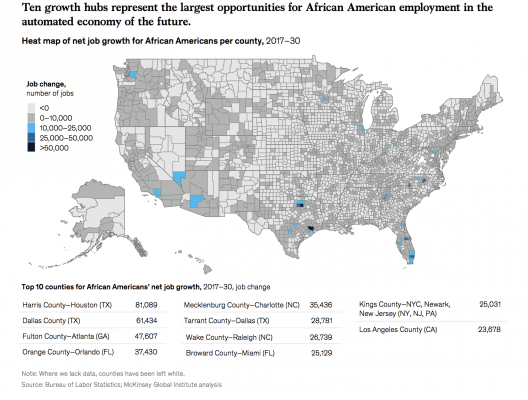

Published in October 2019, McKinsey’s report “The Future of Work in Black America” focused on the threat automation and changing economic conditions pose to Black workers by the year 2030. Their research warns that “African Americans are geographically removed from future job growth centers and more likely to be concentrated in areas of job decline.”

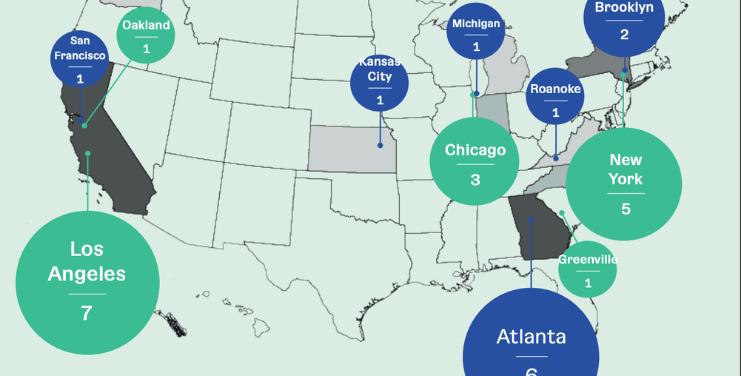

But McKinsey optimistically highlights several areas that could emerge as job-creation centers for African Americans in the future. “Our research suggests that mobile African-American workers, particularly those 35 years old and younger, may find more opportunities in megacities such as Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston or in high-growth hubs such as Charlotte and Orlando.”

Atlanta is no surprise. The city’s No. 1 for African-American affluence and entrepreneurship, with 20 percent of the Black working population self-employed. Since 2000, Black techpreneurs in Atlanta have raised about $300 million in angel funding and venture capital. It’s a fraction of the dollars in SIlicon Valley, but suggests Black founders can find capital in their own backyard.

And when you contrast San Francisco’s 6.5 percent Black tech workforce with Atlanta’s 25 percent (the nation’s highest), it’s easy to see how ATL is the Black tech capital—a position it is not poised to relinquish anytime soon.

Here’s what’s encouraging: Atlanta might be king of the hill when it comes to Black tech hubs currently, but experts believe its success can be replicated. Harin J. Contractor, former economic policy advisor to the Secretary of Labor, explains that other cities must take a measured approach to implementation.

“Too many times local governments engage a race to the bottom mentality where they just cut taxes enough to keep a business or attract a business to come into a community. That hurts your school districts, that hurts your community because there’s no revenue coming in,” he said.

Often, companies that are lured into cities with big tax breaks don’t prioritize hiring local, said Contractor, who worked on economic analysis for key initiatives in the Obama Administration. He advocates a homegrown strategy that focuses less on incentivizing businesses to relocate and more on developing a talent pool so highly skilled that it organically attracts employers.

“If you invested into the community to bring up the skills, you’re going to attract a company to come in because they actually want to hire smart people locally that want to live and work there,” he advised.

Dr. Angela Jackson, partner at venture philanthropy firm New Profit, emphasizes that efforts to bridge the skills gap for willing workers can lead to transformative results for vulnerable cities.

“Investing in reskilling solutions provides direct support for communities most impacted by centuries of unfair policies and practices,” she said. “We are in the midst of a critical inflection point where the investments we make today can shape the economy of the future.”

This is aligned with work being done in New Orleans, a burgeoning tech hub with such a large minority population that “when you say hire local, you are encouraging hiring women, hiring Black,” said Hyma Moore of Greater New Orleans, Inc.

Data from Burning Glass revealed that as a result of being dependent on tourism, New Orleans was one of the hardest-hit metro areas and saw a 72 percent decrease in job postings in March. Moore says the city’s Black female residents are most impacted by the loss of customer-facing jobs, but the city is taking action to prepare them for the Future of Work. Healthcare IT is in demand, for example, and displaced workers can be quickly reskilled for these roles through a learn to earn model.

“We can get your certification from one of the community colleges or universities that are extremely reputable and accredited,” Moore said. “And then you go in and you’re making $65,000 at a tech company. Think about if you have a family or you’re a single mom or dad—bringing in $65,000 after eight weeks of training, it’s life changing in some way.”

CHANGE WON’T HAPPEN OVERNIGHT

Indeed, cities like Atlanta don’t just become tech equity centers overnight. It takes synergy between many parties including workforce development boards, colleges and universities, philanthropy, private corporations, and committed individuals.

The good news is, many American majority-minority cities, from Detroit to Charlotte to Houston, have the potential to be transformed into sustainable centers for Black tech success.

SPONSOR SERIES

This story is made possible with the support of New Profit—a venture philanthropy firm deeply investing in workforce solutions powered by forward-thinking entrepreneurs helping people level up their tech skills and secure opportunities in the new world of work.

New Profit recently announced a $6M initiative to help fund entrepreneurs helping to rapidly reskill American workers for the future of work. Join the challenge!