On February 1, 1960, four students marched to 134 South Elm Street in Greensboro, North Carolina, through the doors of F.W. Woolworth restaurant, and sat at the open counter to order lunch. But they were hungry in the wrong place. There would be no lunch served to these young black students in the whites-only restaurant that day.

For black people in the early 20th century, whites-only sanctioned spaces like theaters, bathrooms, and stores were off limits. Violation of state-sanctioned discrimination resulted in physical violence, arrests, or worse. Today, over 50 years since Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawing segregation, access to safe spaces for black people remains a barrier amid growing gentrification of historically black neighborhoods in urban cities and the ongoing practice of white people calling the police on black patrons at Starbucks or barbecuing in a public park.

Enter the black-owned co-working space.

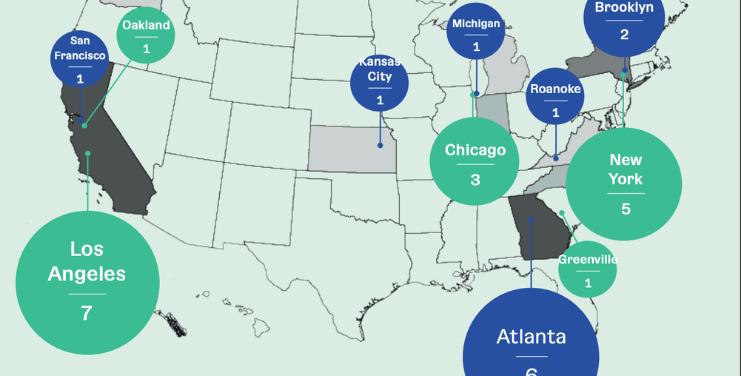

At least 63 of these spaces have popped up in urban communities around the country over the last decade with a particular focus on inclusive innovation, community building, and safety for black patrons. That’s a small fraction of the over 4,000 co-working spaces that exist in some form across the country, supporting over 500,000 freelancers, startup companies, consultants, and emerging founders. According to experts at the Global Coworking Unconference Conference (GCUC), memberships at coworking spaces will double to well over a million, with physical coworking environments reaching over 6,000 nationwide by 2022.

The 63 black-owned spaces emerged adjacent to this growth trend, providing more than conference rooms, Wi-Fi, and limitless coffee: they are built to give black people a safe space to find themselves in the work of innovation where they have largely been excluded. Data from a 2016 study by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation revealed that native-born African Americans comprise of just half a percent of US-born innovators—despite being over 13 percent of the overall population.

Aaron Saunders, a computer scientist and owner of a mobile app development business, opened the Inclusive Innovation Incubator in 2017. Housed at Howard University in Washington, DC, the 8,000 square-foot incubator space is one of the first to open on the campus of a black college in the country. At $200 per month, entrepreneurs get a desk and access to special events, as well as a variety of classes on coding, app development, or growing a startup—most of which are taught by other technologists of color.

“[Entrepreneurs know] that when they come into this space the instructor is going to look like them,“ says Saunders. “This helps when [previously] they didn’t have a safe space to work through the challenges of taking their firm to the next level.”

“Black people held their conversations about tech and innovation in the bars or clubs.”

While co-working spaces in this country’s capitol aren’t hard to come by, Saunders says that these spaces often find it difficult to find diverse groups of entrepreneurs to become members. There’s no solid data on the number of people of color working in co-working environments, black-owned or otherwise. The overall population of freelance workers is growing, however, with black workers making up just under four percent of that population of both incorporated and unincorporated self-employed workers.

“That’s where we come in and own that effort,“ Saunders said. “Having a space that is black-owned and supported by and attended mostly by people of color, it is a good thing. Because it will help more black people come out when before, black people held their conversations about tech and innovation in the bars or clubs.”

Felecia Hatcher, co-founder of Code Fever and Black Tech Week, spent the last two and a half years raising funds from the Knight Foundation and other donors and agonizing over construction plans before opening Tribe Co-Work and Urban Innovation Lab with her husband Derrick Pearson in Miami’s Overtown neighborhood this spring.

Tribe is housed in a two-story, 10,000-square-foot, historic building adjacent to family-owned restaurants, an Italian ice shop, and other black-owned businesses. Hatcher said she has no doubt that this historically black community, established shortly after the incorporation of Miami in 1896, will begin to look a lot different as development projects continue to spread across the city.

“We are one of only two co-working spaces in the entire state of Florida that exist in a black neighborhood,” said Hatcher, who explained that Tribe was created to provide resources for underserved, high-growth, minority entrepreneur businesses.

In Overtown, transformation is nigh, with a forthcoming speed train and other developments breaking ground. Hatcher said she and her team are using the physical co-working space to provide a platform to help educate the mostly black community about innovation and how they too can be involved. On Fridays, co-working space at Tribe is free. The promotion is meant to draw in neighbors and give the greater community a sense of place and participation in the concept of innovation.

“Safe space is important when we talk about the whole conversation on what a co-working space can mean for our communities,“ Hatcher said. “And a space that is more forward-thinking around who is focused on the future of what black Miami means, or culture, or business culture [is important]. Most businesses [here] are focused on survival. It’s important but leaves very little room for organizations to think about once that is figured out what next.”

Ongoing development and neighborhood change in the urban space presents challenges that urban planners like Justin Moore tie to policies like redlining that bred long-time inequality in communities of color.

“Safe and equitable spaces, particularly for black people, is as economic as it is social,” said Moore, an executive director of the New York Public Design Commission and part-time professor at Columbia University. Moore also leads Black Space NY, which works with New York City neighborhoods helping to bridge the gap between developers and residents by procuring conversations and planning sessions to determine how community identity remains amid forthcoming developments.

“Space itself can be designed to help people feel more inclusive. It’s the programming, or the design, a local artist doing interiors or graphics for the space,” Moore said. “There are lots of signifiers that build up to people’s experience and connectedness to the space.”

This story is part of a series of stories produced in partnership with VICE Media’s Motherboard.