KEY INSIGHTS

- Southern states account for 35 percent of all U.S. zip codes but represent 44 percent of all at-risk zip codes.

- For decades, legislators have blocked laws that would bring economic prosperity for Black Americans.

- The $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure law provides an opportunity to help many displaced Black communities.

For decades, Black Americans have faced disparities in income, housing and opportunity. Underpinning these issues, there is a pattern across majority Black zipcodes in the South and Midwest.

An index by the Economic Innovation Group (ECI) found that infrastructure spending in the United States has stagnated from a pandemic-induced recession.

ECI created the 2000 Distressed Community Index (DCI) to understand the divided landscape of American prosperity. Through individuals and community aspects, DCI reveals national growth or lack thereof.

National economic well-being has steadily decreased since 2000. Rural zip codes nationally decreased by 6.8 percent from the 2000 Distressed Community Index (DCI) to the 2020 DCI as the country’s more densely populated areas grew and sprawled. Conversely, distressed rural zip codes increased by 12.7 percent as more rural zip codes fell into the bottom tier.

The Connection Between Race, Zip Code and Wealth

Economic struggles are more severe in southern states, with minorities more likely to occupy the most distressed areas in the U.S. Black Americans, Native Americans, Hispanic and Asian Americans and individuals of other minority groups made up 56.4 percent of distressed regions during the 2014-2018 period, but represented 39 percent of the population nationwide.

The DCI average distress score in 2018 for a majority-Black community, defined as a zip code in which Blacks constitute 82 percent or more of the population, was still nearly two times higher than 42 percent of the majority-white community.

Race and zip code are closely related to income issues. The median household income (MHI) by race and ethnicity for the average Black household in a prosperous zip code is $7,000 less than the average white household. The DCI report notes that the gaps widen for Black households the less prosperous a zip code is. The MHI for a Black household in a thriving region was 92 percent and 66 percent in distressed zip codes, respectively.

The Black median house index fell compared to white households between 2000 and 2018. In distressed communities, Black households have an annual average income of $27,000, while Hispanic Americans average $35,000 and whites average $42,000.

In 2000, the average Black MHI was 90 percent the average of white households in the typical mid-tier community. By 2018, it was only 78 percent. In 2000, a $5,000 income gap separated Black households from white households in mid-tier American communities, by 2018 that loss in income had more than doubled to $11,700.

Consumer Spending By Race

Black communities are spending more than other communities but still face historically high financial burdens.

According to a Harvard study, in the early 2000s the median Black household would spend more than white households, saving only four percent of what they earned. However, Black consumers were twice as likely as whites to purchase higher-priced luxury versions of high-ticket items. For instance, when purchasing a car, Black consumers were more likely to opt for an expensive foreign model such as an Audi, BMW or Mercedes.

Despite being 13.4 percent of the U.S. population, Black households accounted for under 10 percent of the nation’s total spending on goods and services in 2019, according to McKinsey. Black household spending has increased five percent annually over the past two decades, surpassing white consumer spending.

Spending habits and preferences by race are also impacted by age. In 2021, the average Black U.S. consumer is 34 years old, a decade younger than the median age of white Americans. These younger Black consumers are 20 percent more likely to change their spending habits.

The Historical Context For Current Inequity

The overall wealth of Black Americans is rooted in the historical segregation in mostly distressed areas in the Midwest and South.

“In the Midwest, race plays into industrialization and has conspired against the Black community,” Kenan Kikri, Director of research at the Economic Innovation Group, told The Plug. “There are structural biases in federal financing that disadvantage distressed areas.”

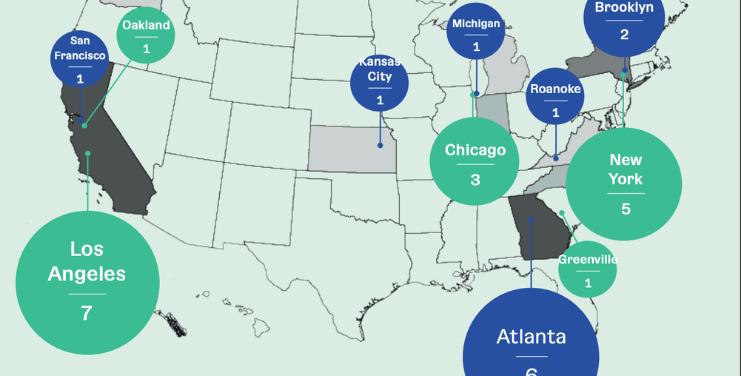

The share of the country’s Black population living in distressed zip codes declined from 45.6 percent in 2000 to 35.3 percent in 2018. But in the Midwest, half of the Black population still lives in distressed communities. Prosperous zip codes have grown from 16.3 percent to 26.9 percent, slightly higher in growth compared to the non-white population nationally, which climbed from 30.9 percent to 38.9 percent.

More than half of Black Americans live in a distressed community in the Midwest, considerably higher than Southern states where 35 percent of Black Americans live in a distressed zip code.

Despite this, Black communities remain significantly underrepresented in prosperous communities. According to the DCI report, there would have to be 10 million more minority residents in prosperous communities for their share of the quintile’s population to match their percentage of the national population.

The segregational use of laws and redlining in the Midwest and South made wealth prosperity, home access and overall wellness hard for Black Americans.

The South was the first region in the U.S. to block local ordinances from taking effect or dismantling an existing law (preemption) which often denied Black Americans the resources they needed. The configuration of government, discriminatory policies and other ordinances were implemented to limit the rights and freedoms of Black Americans and entrench white supremacy during the dismantling of Reconstruction-era economic and political gains.

In 1867, a series of radical Reconstruction Acts helped Black Americans be elected to the U.S. Congress, state and local positions.

These positions prompted Black constituencies around the country to advocate for policies to support enfranchisement and equal rights, criminalize lynching and suppress the Ku Klux Klan. However, from 1869-1867, there was a vast electoral backlash due to Ku Klux Klan voter intimidation that allowed white conservatives to replace Black public officials in Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia and Mississippi.

Many Confederate statues and symbols of oppression still stand today in parks and schools. Areas that had more lynchings and group killings historically have more streets named after Confederate generals today. These areas also tend to have lower Black voter registration rates and more officer-involved killings.

The Midwest faced similar legislative restrictions for Black Americans in housing and the workforce.

The pandemic has revealed many issues for workers in the U.S. workforce system. Low-wage workers are particularly vulnerable in the economic system according to an Economic Policy Institute report.

“Sometimes people who are making the decisions in the policy arena, having not lived the experiences that assists with your understanding of the need,” Venessa Womack, Black Belt Region advocate, told The Plug.

In the 20th century, six million Black Americans moved out of the South to Midwest cities, a period known as The Great Migration, where they found work in factories. The increase of Black individuals motivated white lawmakers and business leaders to develop a collection of systems and policies that racially segregated Midwestern cities by neighborhood or preemption tactics.

Black Americans were restricted in living arrangements organized by private and government housing practices. In the 1930s, the Home Owners Loan Corporation, a federal agency refinancing home mortgages currently in default to prevent foreclosure, created “redlining” maps to prevent Black homeowners from getting mortgages for homes in white neighborhoods. Similar policies encouraged banks to refuse loan access to Black Americans.

White lawmakers also stripped public services that greatly impacted working women of color and other minorities in organized labor. For example, today union workers are paid, on average, 11.2 percent more than workers in similar jobs with similar education and experience. Black union workers are paid 13.7 percent and Latinx workers 20.1 percent more.

In the 1980s, better labor unions assisted with stronger economic conditions for working families in the Midwest—especially Black and Brown workers, who were more likely to be covered by union contracts than white workers. However, between 1983 and 2020, Midwest labor unions declined more than the overall national decline.

A $1 Trillion Opportunity

National funding like the Build Back Better Infrastructure law could be the sought-after turning point to sustain economic and wellness opportunities for Black Americans. Despite some earlier opposition, the law was passed. The bipartisan law can revitalize Black American communities and decades of disenfranchisement.

Many past corporate monetary decisions will change with the infrastructure law. According to a report by the House Committee on the Budget, corporations with over $1 billion in profits to shareholders pay at least a 15 percent tax rate on these profits. The law also imposes a one percent excise tax on publicly traded U.S. corporations for the value of their stock buybacks, which are usually for their shareholders rather than invest in their companies or workers.

The law would also close the over $7 million tax gap from the wealthy invading taxes. Wealthy Americans would pay the taxes they owe by strengthening the Internal Revenue Services’ (IRS) ability to audit those in the highest income brackets. This investment will help build a more equitable tax system and help close the tax gap and generate funding.

The law also has housing provisions for residents of public housing. Sixty-five billion dollars to repair and renovate public housing, which will be reserved for the nation’s public housing stock to enhance living conditions for more than 1.8 million public housing residents.

Currently, one-third of Black renters pay half their income in rent. Build Back Better will help build and improve more than one million affordable homes and vastly expand the availability of housing options.

An estimated $25 billion will go to increase the supply of affordable housing through the National Housing Trust Fund and HOME Investment Partnerships Program, which also provides $26 billion for a Housing Choice Voucher and other rental assistance programs, which help people afford private apartments. The voucher will be doled out over five years, with funding to maintain them through 2029.

The housing voucher also advances other infrastructure agenda investments, according to The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report. The housing vouchers could strengthen home security for more benefits in access to high-speed internet. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act adds new improvements to several Black Belt Regions, a historical term for where the majority-black population grew as a consequence of the expansion of slavery, to enhance and increase services and opportunities.

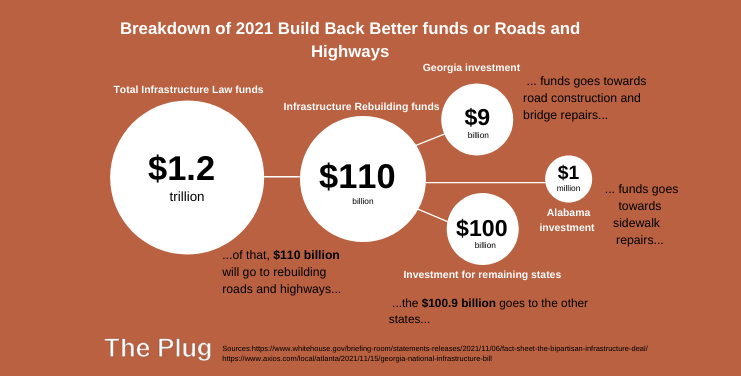

The bill also allocates $110 billion towards roadway safety to communities, potentially funding everything from tougher speeding enforcement to new crosswalks, safety lighting and underpasses beneath busy roads.

The U.S. Senate unanimously approved an amendment adding congressional authorization of the full Interstate-14 five-state corridor expansion. The highway will stretch through Alabama from Demopolis, Selma, and Montgomery, before exiting the state south of Opelika.

The interstate would end at Augusta, Georgia.

Georgia will receive nearly $9 billion to fix roads and highways, plus $225 million to upgrade and replace deficient bridges. In 2019, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave Georgia’s roads a C+ on its infrastructure report card, arguing that the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) lacks the funding to maintain its roadways adequately.

Over 2,260 miles of highway across Georgia are categorized as in poor condition. The state also has 374 bridges that have been deemed “structurally deficient,” including the Interstate 75 to Swamp Creek in Whitfield County that has over 66,000 daily crossings.

Alabama will get much-needed assistance with roadways and highways. Auburn’s Safe Transportation for Every Pedestrian In Underserved Communities Program plans to utilize $1.3 million in federal funding to design construction plans for sidewalk improvement projects across the state.

Many counties have incomplete sidewalk systems, crumbling and failing to meet ADA compliance. Fixing the sidewalks will make these communities more walkable, convenient and safe for pedestrians. Pedestrian fatalities have seen a dramatic increase in the United States over the last decade, with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reporting over 38,000 traffic deaths since 2007. Many of those deaths were pedestrians hit by cars. Increased focus on past issues will make Black prosperity rise.

Black Americans have experienced economic restrictions throughout history that give way to current disparities. However, more attention and funds are put towards Black communities to fix systemic and modern problems.

Sponsored Series: This reporting is made possible by the The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation

The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation is a private, nonpartisan foundation based in Kansas City, Mo., that seeks to build inclusive prosperity through a prepared workforce and entrepreneur-focused economic development. The Foundation uses its $3 billion in assets to change conditions, address root causes, and break down systemic barriers so that all people – regardless of race, gender, or geography – have the opportunity to achieve economic stability, mobility, and prosperity. For more information, visit www.kauffman.org and connect with us at www.twitter.com/kauffmanfdn and www.facebook.com/kauffmanfdn.