Key Insights:

- The May 2020 murder of George Floyd sparked racial unrest throughout the world and simultaneously shifted the DEI industry.

- For some companies, the effort to prioritize DEI is a passing phase but for professionals in this space, the work has just begun.

- With billions being spent and new technologies advancing the industry, the face of DEI may change forever.

Over the last 50 years, the diversity, equity, and inclusion industry have gone through many transformations. With the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020 and the global protests against racial injustice that followed, the industry again sits at an important crossroad.

In the three months following the murder of Floyd, DEI-related job openings increased by 55 percent but quickly rebounded, falling by 60 percent amid the early months of the ongoing pandemic according to data from Glassdoor.

This boom in jobs came against the backdrop of corporations giving their employees a day off on Juneteenth (before it was officially recognized as a federal holiday), billions of dollars pledged to racial justice initiatives, and the exorbitant amount of promises to increase racial diversity across various industries. Corporate America spends at least $8 billion annually on diversity training alone according to a 2017 report from McKinsey.

The events of the last two years have again situated the industry in an optimal position as the issue of structural racism, explained through best-selling books like How to Be an Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi, and Nice Racism by Robin DiAngelo, has fashioned a stronger grasp on the attention of corporate leaders.

A Brief History of the DEI Industry

The modern DEI industry can be traced back to the 1940s to a German-American psychologist named Kurt Lewin who was recruited by the Connecticut Interracial Commission, the nation’s first state race-relations board created to “investigate the possibilities of affording equal opportunity of profitable employment to all persons.”Lewin was tasked with training corporate leaders to deal with intergroup tensions in their communities and how to comply with the Fair Employment Practices Act.

His goal was to create workshops that offered a better way to change people’s attitudes and beliefs and provide participants with evidence of how their actions affected others. These initial workshops evolved into the creation of the National Training Laboratory, where the term ‘sensitivity training,’ was born.

With the passing of the Civil Rights act in 1964 and the increase in the number of women and people of color entering white-collar jobs, the DEI industry went through its next iteration. These initial efforts focused on compliance with this historic piece of legislation.

As time passed, conversations started to evolve and discussions started to shift from what is required of a company based on the law to how companies could create more equitable and inclusive environments where historically marginalized groups felt equal.

In 1987, Workforce 2000 was published by the Hudson Institute, a right-leaning policy research organization, which highlighted four key trends that would shape the American labor force in the final years of the 20th century, one of which was that the current white-male dominated workforce would see a large demographic shift made up of “the net additions of women and minorities.”

Throughout the nineties and early 2000s, rhetoric began to majorly shift from compliance to diversity, and topics started to shift from just race and gender to other aspects of a person’s life including sexuality, work-life balance, age and disability. This notion of acknowledging the different oppressed intersections of a person’s identity has been branded as “inclusion.”

In 2007, a New York Times survey of 365 HR professionals and diversity specialists from different companies with an average of 10,000 employees, found that 55 percent of respondents had a diversity department and over 80 percent had taken either mandatory or voluntary diversity training.

Recently, some of the largest corporations, such as Apple, have gone on the record as saying that “the most innovative company must also be the most diverse.” Organizations not only understand the legal and moral imperative of diversity, they also understand the business imperative, with research from McKinsey finding that companies with more diverse executives are 33 percent more likely to see above-average profits.

With the abundance of acronyms, ranging from “DEI,” to equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) to diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging (DIE&B) to concepts such as cancel culture and critical race theory, the concept of equity in the workplace is once again in flux.

These new types of racial sensitivity training were the subject of an Executive Order under the Trump administration which sought to cancel any racial sensitivity federal contract that the administration labeled as “un-American propaganda training sessions.” President Biden reversed the order on his first day in office.

Current State of the Industry

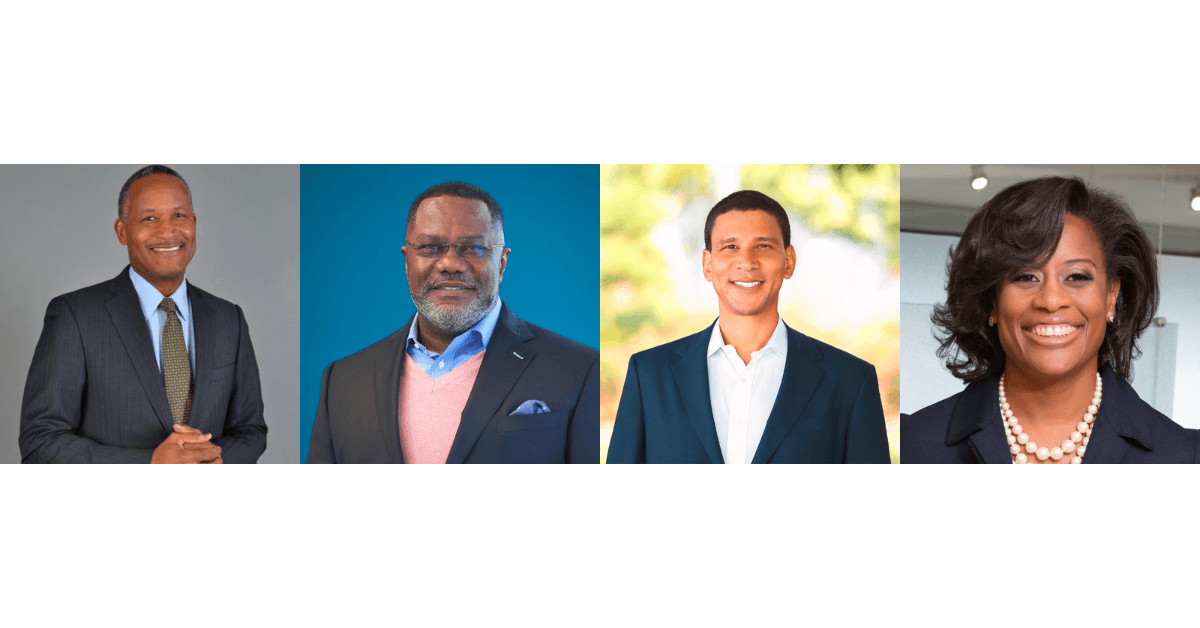

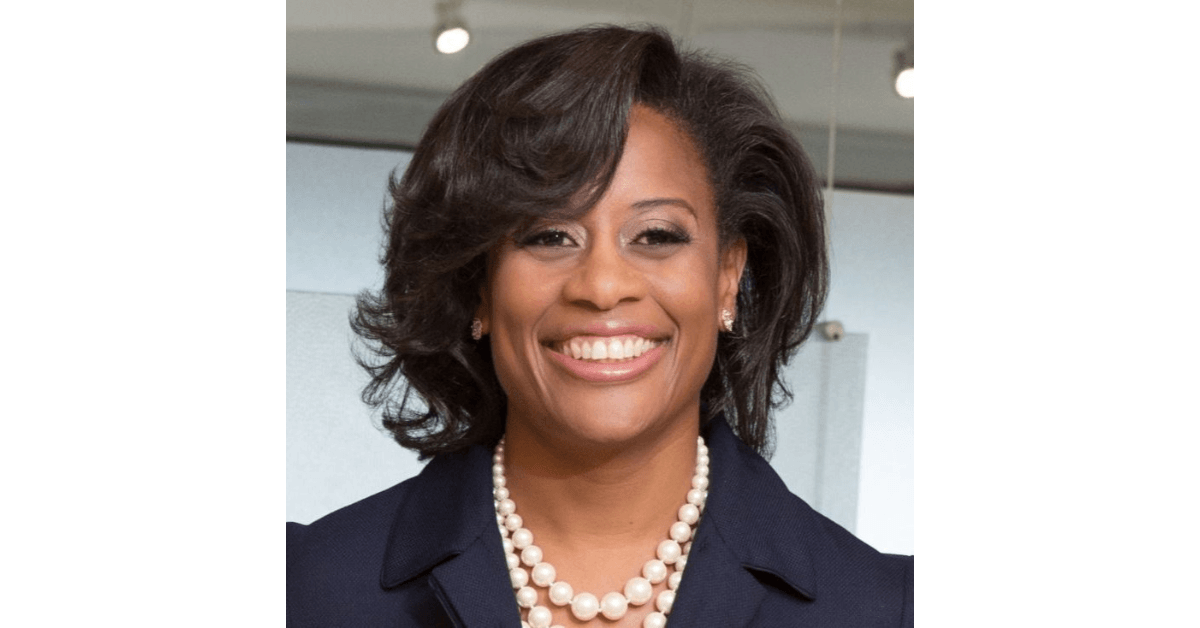

In January of 2020, Dennis Maurice Dumpson started #InvestBlk, a boutique racial equity and strategic planning consulting firm that was struggling to get clients, but by June, requests for support from organizations were filling his inbox.

“I started #InvestBlk because professionally there was no space to discuss how to be equitable and culturally competent in the workplace,” Dumpson told The Plug.

Although conversations around equity and race were increasingly more common prior to 2020, many companies felt and looked woefully unprepared in dealing with the uproar after the video of Floyd’s murder surfaced.

“When we saw the murder of George Floyd we saw a lot of reactiveness, opposed to responsiveness,” Sheree Atcheson, a global DEI executive who has worked primarily with tech companies for more than a decade, told The Plug.

Almost two years since the racial unrest sparked by George Floyd’s murder, the hunger for DEI consulting has seemingly waned.

“After we got out of the guilt-mongering for racial equity and started to think strategically about how to implement structural change, organizations are starting to step away from the work,” Dumpson said.

The passion that pushed companies to make billions of dollars in pledges and commitments is finite according to Atcheson, and companies that are invested in seeing real change are dedicating resources to strengthen internal infrastructure and data capabilities.

“Representation data isn’t enough,” Atcheson said. Companies that are serious about addressing societal issues that seep into the workplace are starting to look at inclusion metrics that are disaggregated by race.

Investments in implementing structural change according to both employees and consultants are one of the most important investments that corporations can make. The Plug spoke with an employee at one of the country’s largest tech companies who requested to speak under anonymity who said that it was equally important to consider changes the company is influencing outside its employee base, through programs and initiatives supporting businesses of color or creators of color.

Those taking on DEI work, both internally and as consultants, are also increasingly arriving with different educational backgrounds and work experience. Eric Johnson started as a DEI consultant for a talent management consultancy in May 2021.

They came into their role with a background in education. “I began in the DEI space as an educator which isn’t really thought of as DEI work but I had to be values-centered,” Johnson told The Plug. They mostly worked with low-income and Black families and frequently engaged in conversations about race, equity, and sociopolitical issues with other educators.

As the DEI industry steps into its next phase, experts believe that it must incorporate more theories grounded in sociology, psychology, and ethnography. Ideas like decolonization, land acknowledgment and even reparations are starting to come to the forefront.

What’s on the Horizon

Last year, Mark Zuckerberg the founder and CEO of Facebook announced that the company would now operate under the moniker Meta. According to the announcement, the shift aims to bring together the various apps and technologies the company runs under one new brand and launch the metaverse. The metaverse is still being defined, but will likely be made up of different virtual worlds that can be accessed via virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR). The metaverse is still in its infancy, but VR and AR technologies are already being widely used in other industries, most notably, gaming but increasingly in DEI.

The next generation of DEI companies are utilizing new technologies are revolutionizing ways to expand empathy and how people understand injustice. Praxis Labs, a learning platform utilizes VR to create a new type of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion training. The company, which raised over $15 million in its Series A round, was founded in 2019 after deep exploration of how emerging technology and immersive experiences could be applied to DEI topics according to cofounder Elise Smith.

“I was compelled by the visceral nature of perspective-taking immersive experiences and even more excited by the research that was showing psychological responses in VR are similar to those in real life,” Smith told The Plug.

Praxis Labs builds virtual experiences for employees to walk through scenarios from the perspective of someone experiencing the incident of bias and as a bystander or someone complicit in an incident. Employees are then prompted to decide how they want to respond, which the company believes helps them develop a repertoire of responses for when those experiences inevitably happen in real life. These experiences, according to Smith, help employees build empathy for the experiences of others and have a safe space to practice how to intervene.

With the deepening intersection of tech, social justice theories, and DEI practices, experts hope that the misconception that anyone can engage in the work of DEI halfheartedly will dissipate.

According to Dumpson, who is in the process of developing a programmatic framework for his work, “this work has to be strategic and dig deep into nuances, and it’s often not framed in this way.”