KEY INSIGHTS

- The #BlackTechFutures Research Institute is creating a vision for how Black Americans are centered, reflected and respected in tech.

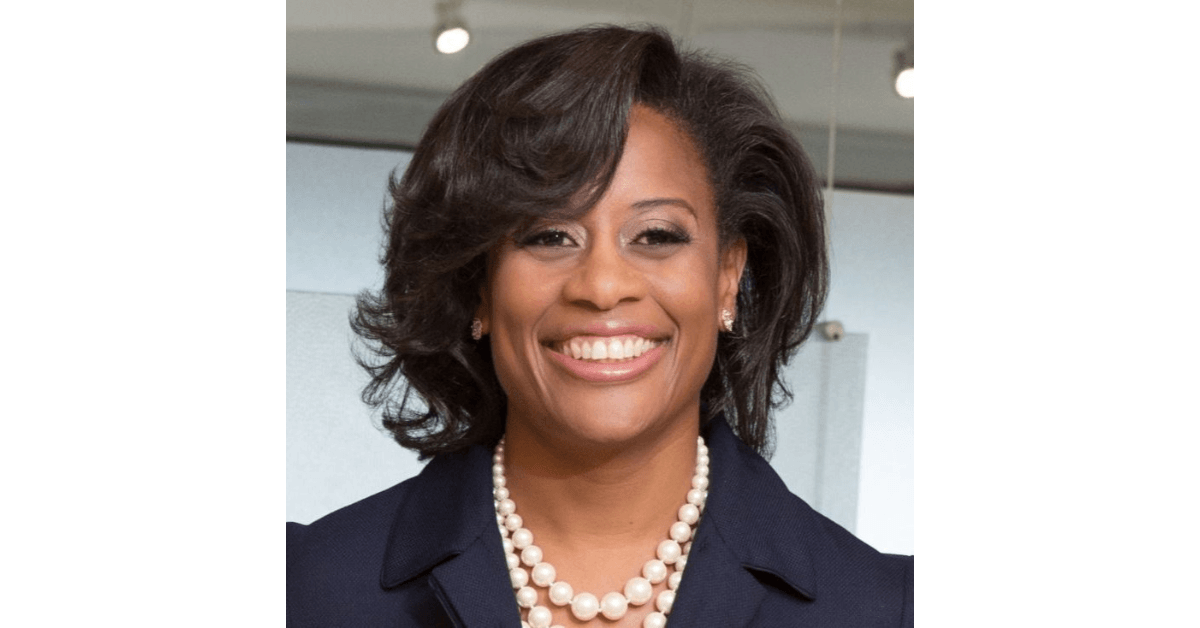

- Fallon Wilson, the co-founder of the institute, is prophesying about that future.

- Wilson believes the Black tech future is anchored around HBCUs, faith-based institutions, and Black women and Black trans women.

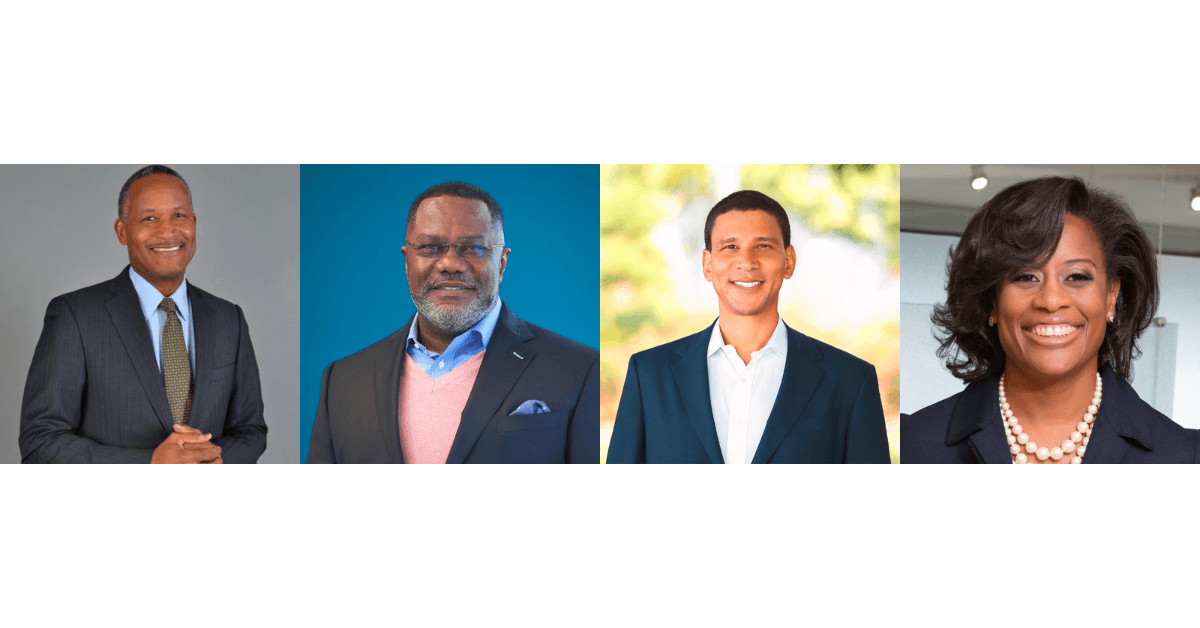

This is the third installment of The Plug’s new series of periodic deep dives with the executives and organizational leaders driving change, The Insight. Read our previous installments with the Presidents of Morehouse College and Paul Quinn College.

Fallon Wilson isn’t behind a pulpit, but she’s preaching.

“The #BlackTechFutures Research Institute is committed to creating Black joy futures. That is our outcome. That is why we exist,” Wilson, the co-founder of the institute, is animatedly telling The Plug.

The future of the jobs Black Americans have is set to be disrupted because of automation. A 2021 report from the McKinsey Institute for Black Economic Mobility estimated 42 percent of the Black labor force currently hold jobs that could be impacted by 2030.

But Wilson isn’t waiting for the disruption. She is actively working to create a world where Black Americans are centered, reflected and respected in tech.

“We want Black people to be able to create and make choices in the automated world based on their values and based on their sense of self, and to do that you have to think about liberation from all parts of our tech ecosystem,” Wilson says.

Wilson has been making her vision clear for years. In 2019 on a TEDx stage in Nashville, she laid out her prophecy for the future of tech.

“I dream of a national unified Black tech ecosystem reminiscent of Black Wall Street before white supremacy annihilated it,” she told the audience. “I dream of a flesh and blood Wakanda-like ecosystem.”

The #BlackTechFutures Research Institute launched in 2020 in the wake of her prophesying. Wilson and Stillman College, an Alabama-based HBCU, received a nearly $400,000 grant from the Kauffman Foundation.

Next week, the institute is hosting its 2022 Black Tech Policy Week, inspired by the vision Wilson laid out in her TEDx talk.

The Plug sat down with Wilson for an in-depth conversation about what a Black tech future looks like to her, why HBCUs are central in the vision and how building Black joy datasets is critical to training machines to see more than just deficits.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

—-

Mirtha Donastorg: Now the title of the institute specifically is hashtag BlackTechFutures. Why the hashtag? What does that denote for you?

Fallon Wilson: We want a digital archive. So 100 years into the future, where we have machines using all types of datasets to understand reality, we want to know that we were an organization that was committed to creating futures for Black people. And so it’s digital archiving immediately for searchable information about the work we do.

But it also says that we create our own futures. So technically, I’m creating a future even in this moment with the hashtag about what we should be doing for our community that’s led by Black people and envisioned by Black people supported by a Black institution, Stillman College.

That’s really interesting because you guys aren’t just talking about the future that you want, you are already envisioning what the future will be and setting up these institutions that will be able to fit into that future.

It’s like prophesying. Prophesying that number one, we will exist in the future. It is also prophesying that eventually this can be used as a type of data set to talk about how Black people live their lives, so we’re trying to build within an automated future. It is both inspiring but also practical.

I like the idea of prophesying, it kind of reminds me of Octavia Butler…

Oh, don’t ever, ever shy away from talking about Octavia Butler, and Parable of the Sower or that Afrofuturism or Afrojujuism. That is what we exist as. Part of the work that we do, we do a lot of research and policy, but when I say Black joy, how do you operationalize Black joy for Black people? It means that they’re at the center of our research design, the methods and the interventions we do.

And so the notion that Octavia Butler, N.K. Jemisin or all these amazing Afro-futuristic writers envisioned this moment before this experience is why we exist. It is because Black people have always used our creative imaginations to see ourselves free and liberated, and we just operationalize that through data, research and policy.

But we’re doing no different than what our foreparents and ancestors have done in this moment. We just use this new tech form to do it.

Black people historically, to live in a racially alienated society, have always had to use a creative imagination. Whether it’s through envisioning transnationalism, or Pan-Africanism. Whether it’s envisioning freedom through civil rights, we’ve always had to do this in a world where we were not valued.

And so yeah, our work is about joy and prophecy, but we are practical. And we work with historically Black colleges and universities to really operationalize this work because we see them as anchors in our vision.

Is it the fact that HBCUs have a 100+ year-old institutional system already set up that can then buoy the work that you’re doing? What exactly is it that HBCUs can operationalize for you?

I have to tell you our model to tell you how HBCUs fit in it. We believe that in order to address the racial tech disparities in K-12, our youth have access to computer science teachers in public high schools. If we’re talking about the post-secondary environment who’s in the classroom and who’s teaching STEM. Whether we’re talking about capital for tech entrepreneurship, attrition and retention for Black tech companies, or how governments are thinking about dollars for Black people, we believe you have to have an ecosystem approach.

Within that ecosystem, there are three seminal anchor institutions that need resources so that we can have a tech future, of them are historically Black colleges and universities. To your point, they have existed and were created to help Black people acculturate into a society that did not want them to exist. HBCUs, like Black churches, are historic institutions that have to be re-engineered for this new world of automation.

HBCUs are the reason why we have a Black middle class. It is a reason why we have Black innovators. Because of that and because they play a central role in organizing many cultural traditions, whether we’re talking about festivals, faith, fraternities and sororities, they are essential to the work that we do.

We actually have amazing research that is coming out of our HBCU system, so I think the work we do is to highlight historically the work that these amazing institutions have done. They are the vanguard of this new movement for technology ethics and social justice. Unlike so many of our predominantly white institutions, HBCUs have always had to think about justice, because they’ve worked with students who were impacted by unjust systems.

And they are anchors. There’s no way forward without them, without faith-based institutions, and without Black women and Black trans women. Those are my three pillars when I think about a Black tech future. They all have to be given the resources to grow and thrive because historically, they have done such huge work to get us to where we are at this moment.

Speaking of Black tech futures, was that inaugural Black Tech Policy Week in 2020 kind of the culmination of the dream that you prophesied and talked about in your TEDx talk?

The dream? Oh, no, no, no, no. That is like the seeding of the prophecy. The fulfillment of the prophecy is that we will have a national Black tech ecosystem aligning all of those working with and across cities to a common agenda. That would allow for us to address important research questions like, what does it mean to live in a cashless society when so many Black people are unbanked, yet we’re building a national cryptocurrency system of economic outcomes?

We could be able to answer that question because we’re all aligned. Or what does it mean that cities are developing smart city plans where they’re using data surveillance to improve city congestion, while compiling databases and tracking Black and brown bodies out of their neighborhoods and giving that information often to law enforcement without any data design justice principles attached to it? Another question that would come from a national Black tech ecosystem is, what does it mean to build Black joy datasets so that we can train machines to see us more than as deficits?

And so that for me is the fulfillment of prophecy when I can answer those questions collectively. The Black Tech Policy Week is the seeding of that because we bring together historically Black colleges and universities, we bring together race and tech centers, and we all have a very strong conversation about how we work together to ensure that Black people can make decisions for themselves and their families in a fully machine-driven world.

I feel like there is sometimes a lack of choice in our current tech reality that the people who have the resources and are kind of the gatekeepers to opportunities also have these abysmal human rights records or treat Black folks in this country poorly.

I want to get your take on a dilemma that I ask HBCU leaders about often. How do you think HBCUs should consider partnering with companies that either have historic or recent allegations of discrimination even though they are clear, lucrative pathways into tech? So like the Apple’s, the Google’s.

I would say two things as an observer of the space and as a researcher in this space. The first thing I would say is, I support companies’ pledges to do what is right by HBCUs. I think it is good that they create the pledge and I think it is good that they fulfill the pledge. Let me start there.

However, I do have some challenges here. I think they have an intention to do right. However, it has only been the last six years that they start publishing their own demographic data about who is employed in their company, and what positions they’re employed in. I can only expect them to do so much given that they have a lot of internal work to do.

It’s why I love Stillman College and why I love President Warrick, and senior adviser Isaac McCoy on all of the research work that we’re doing with the #BlackTechFutures Research Institute. Because, unlike any other HBCU, they took a Black-owned, created idea backed with dollars from foundations and are incubating my research institute as their research institute in partnership to do transformative work. They took me instead of taking an Apple or a Google who are bringing millions of dollars, but they believe in me.

I think it is important to have access to companies and to support their desire to come and work with HBCUs. But I will always tell presidents to be conscientious about the limitations of what the gift means and that [companies] always want a return on investment. Whether it’s an investment to show to their investors that they’re committed to this or some other outcome, you have to read the fine print.

I believe companies can be partners and I work with them on so many different things. But I’m also clear about the limitations and also the need for HBCUs to do what Stillman has done — we are great but we know that there are amazing researchers like Dr. Wilson out there. Let’s incubate her research, let that be our research institute. Let us drive this conversation of innovation, culture, and data through the lens of supporting a Black genius and her amazing team.

So then, in terms of the Black Tech Policy Week that is coming up, what will that entail? What can our readers expect if they attend?

What your readers will expect is dreaming.

If you tune into Black Tech Policy Week, you’re tuned into a week of dreaming of our futures. You’re going to talk with leading scholars and practitioners who are not just thinking about bias algorithms. That’s only one part of an issue and an opportunity that Black people have to negotiate. What about telehealth? What about the number of micro-businesses that are growing online? But yet we know that 29 percent of Black people still don’t have access to the internet. We are looking at practical nuts and bolts that will be bolstered by amazing Black tech talent– scholars and practitioners who would tell you, ‘I have a dream to solve that problem. I have a solution to solve that problem.’

This week is about dreaming of our futures.

Now, you’ve been doing this work for a very long time, you know, before 2020 shifted many people’s attention to HBCUs and Black Americans. Have you felt any sort of similar shift in how your work is regarded? Does it feel like an actual sort of tectonic shift? Or is it fleeting?

Okay, so I have two answers to that. The first answer I would say, I suspect the funding will be fleeting, because many of our foundations and companies and private donors, they’re episodic when it comes to funding and also the notion of disremembrance of issues. We don’t necessarily have a long track record remembering why there was such pandemonium around supporting HBCUs because of George Floyd and a pandemic. So you know, disaster politics or disaster giving, I just don’t know if that’s sustainable.

You talked about shifting, I think there has been a tectonic shift in the types of questions that Black people are now asking about this moment. And to me that is more profitable than talking about the capital that we may have gotten that may be seasonal. So for me, if there was a tectonic shift, it was the level of questioning that I’m getting from Black people about futures, about their Black tech futures, about their community futures.

The level of questioning has gone to, ‘Okay, I know you used to talk about the robots are coming … So maybe the robots are here Dr. Wilson, how do we as a community get ready for the decimation of jobs? How do we do digital upskilling Dr. Wilson?’

So the questions from Black people themselves are probably the tectonic shifts that I’m noticing more so than anything.

—

Working to create a future where Black people are an integral part of the tech ecosystem will require more than just increasing funding for Black tech start-ups or creating recruitment pipelines into Big Tech. Though those are important pieces, it will require having a clear vision and framework for a truly equitable tech future that doesn’t replicate the biases of the past. Fallon Wilson and the #BlackTechFutures Research Institute are helping shape that vision.