Of the many racial disparities the uprisings of 2020 spotlighted, the lack of access to opportunities and capital that Black and brown entrepreneurs face was one of the most prominent.

“We saw a lot of folks, particularly Black people and women who didn’t have networks, and even though they were doing big raises, they were not getting venture capital,” Brandon Brooks told The Plug, Founding Partner at Overlooked Ventures.

In 2016, VC backed startups created around 2.6 million jobs, according to the Census Bureau’s Business Dynamic Statistics.

The industry has simultaneously been plagued with racial and gender gaps in hiring and investing. While a record $150 billion was invested in U.S. startups in 2021, just 2.6 percent of VC funding went to Black or Latinx founders, and even less went to women-led startups.

Many venture capital firms do not track racial diversity data, but BLCKVC, a non-profit that supports Black investors found that Black investors make up less than 3 percent of industry professionals.

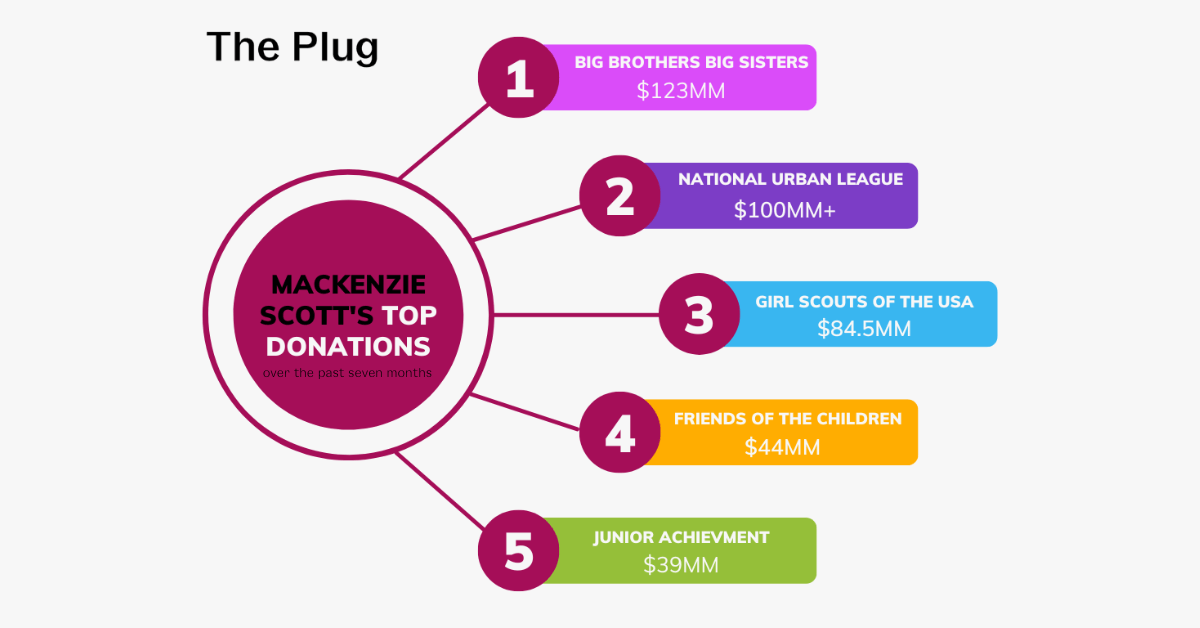

Companies and venture capitalists felt pressure to address these disparities in ways that they never faced in recent times. In the immediate wake of the murder of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, notable companies like Apple pledged $100 million toward racial justice initiatives, $10 million of which went to Harlem Capital aimed at investing in diverse founders.

Other corporations like Target and Sephora, pledged to commit 15 percent of their shelf space to Black-owned brands. By June 9, 2020, less than a month after George Floyd was murdered, U.S. companies had pledged $1.9 billion toward racial equity. A year on, the pledges have skyrocketed to $50 billion, though only $250 million of that has been deployed.

“Most folks don’t know what VC is,” Brooks said. “To get your foot in the door, you often need a warm intro, and a lot of the work to pitch a VC is done behind closed doors with little transparency,” he continued. ”We are very transparent about who is funding us and whom we intend to fund, and this should be a requirement among all VCs.”

At the end of 2020, Morgan Stanley commissioned a survey of 76 VCs with an average equity check size of $2.65 million to “bring attention to the funding gap for women- and minority-owned startups.”

The study found that 75 percent of VCs surveyed agreed that it was “possible to have an investment strategy that intentionally invests in women and multicultural entrepreneurs, while still maximizing returns,” a 20 percent increase from 2019, and 61 percent said the Black Lives Matter movement impacted their investment strategy.

While the increased attention to the disparities in lack of access to capital and venture funding for Black and brown entrepreneurs is needed in a field mostly dominated by white men, policy experts have long argued that the racial wealth gap will not close simply through increased minority entrepreneurship.

A report published earlier this year in the Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy found that Black-owned businesses are less likely to remain open beyond four years compared to white-owned companies and are more likely to experience downward economic mobility.

They recommended that instead of focusing on increasing the rate at which Black people become entrepreneurs, those hoping to grow Black wealth should instead focus on improving the rate at which Black entrepreneurs succeed.

As issues of equity and race continue to rise to the forefront of wealth conversations, VCs, particularly those focused on building wealth among people of color, may have to enter the policy realm in ways they never have before.

“The wealth gap can be closed,” Melissa Bradley, founder of 1863 Ventures told The Plug. In her view, there are three vital things that must happen for that goal to be reached.

“We must undo or eradicate all of the structural policies that continue to sustain the wealth gap. Second, we need to level the playing field when accessing capital in all forms—grants, debt, and equity.”

Bradley continued, “policy stops the gap from widening, and capital helps close the gap.”

She said there must also be an intentional education component because people of color have long been locked out of the market. As a result, they now lack the confidence or knowledge to invest and build their capital.

The stark wealth gap is not for lack of trying on the part of entrepreneurs of color. Black entrepreneurs start businesses at higher rates than other groups, according to researchers at Babson College.

This raises the question of how much of the onus should be put on entrepreneurs and VCs that fund them in addressing wealth inequality?

McKeever “Mac” Conwell, founder of Rarebreed VC, doesn’t think funders should hold full responsibility. “Everyone wants to put the onus on venture capital, but we’re only a small piece of a larger picture,” Conwell told The Plug.

Limited Partners, should also play a more significant role in policy discussions regarding wealth creation, according to Conwell. “In the wake of George Floyd, you didn’t hear from institutional LPs. You heard from VCs because everyone knows them, but no one knows about the pension funds or endowments because they’re not sexy, but they are the top of the food chain.”

VCs, therefore may not be the entity to address the racial wealth gap—they have the potential to spur the next generation of Black and brown entrepreneurs, some of whom will get wealthy, according to Conwell. However, nothing is making newly wealthy people of color invest back into Black and brown communities.

“You can’t force anyone to do what you want them to do,” Conwell said. Moreover, while one may hope or expect wealthy people of color to uplift others who look like them, no law says they must.

A year and a half into the Covid-19 pandemic and studies are already showing that Black wealth is likely to decrease.

Advocates like Bradley believe that as more and more VCs show interest in addressing racial disparities, they must put their weight behind policies like alternative credit scores, more equitable procurement processes and guarantees that federal grants and SBA loans get to people of color.

Some progress has been made in this respect, when Congress passed The American Rescue Plan, it provided $10 billion to the State Small Business Credit Initiative, a program intended to provide capital to small businesses and startups in underrepresented regions and communities.

The Next Generation Entrepreneurship Corps Act, which would also encourage job creation in underserved communities through a $330 million investment in a competitive fellowship for entrepreneurs, which plans to create 320 businesses each year.

Many have said that the events of 2020 have caused a type of racial reckoning within society that we haven’t seen since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960’s.

An industry dedicated to identifying and investing in opportunities to create new wealth will be particularly important in seeing that reckoning come to fruition for the people of color who have often been left out.