In just 15 seconds, Keara Wilson became a star. Last March, as the US went into lockdown, Wilson uploaded a video to TikTok of her dancing to “Savage” by Megan Thee Stallion, launching the viral #SavageChallenge. More than a year later, the 20-year-old will finally have the copyright to that choreography.

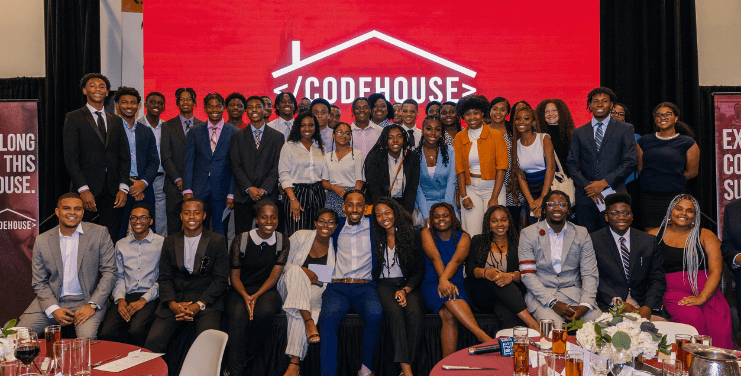

Logitech, the computer accessories company, and famed choreographer JaQuel Knight, who created Beyoncé’s iconic “Single Ladies” dance, have teamed up to help 10 Black and brown creators get the rights to their choreography. With a copyright, no one can reproduce their work, create a derivative version of it nor perform it in public without their permission.

“This is not just about dance, it is about justice and change,” Meridith Rojas, Global Head of Entertainment and Creator Marketing at Logitech for Creators, told The Plug. “Initially this was not considered intellectual property and I think the thing that is so obvious is when other people are profiting off of it and it’s being extracted into these other tangible forms, it absolutely is intellectual property.”

The business of going viral

TikTok is a booming business. The app’s top earner, Addison Rae Easterling, made an estimated $5 million in 2019 alone. She rose to prominence partly by performing viral dances and has successfully monetized that fame.

But many Black TikTokers say Rae exemplifies a culture of extraction on the app. In March, she taught Jimmy Fallon eight viral dances without crediting any of the original creators, including Keara Wilson, who are mostly Black. After the backlash, Fallon had some of the originators on his show to perform their own dances.

Black creators’ dissatisfaction with the way TikTok and its white users profit off the dances and trends they create without credit came to a head earlier this summer when some of them went on strike, refusing to create dances to a new song by Megan Thee Stallion. Looking at Forbes’ list of highest earning stars on the app further illustrates this point — none of the creators are Black.

Viral dances are not just on social media apps, but can be seen everywhere. Young Deji, one of the artists Logitech and Knight are working with, is credited with creating “The Woah” dance. When Rojas was shopping for clothes for her son, she saw a shirt with a teddy bear doing Young Deji’s dance, she said.

“Traditionally, copyright laws said you can copyright art if art is in tangible form — so it’s painting, drawing and sculpture, but then when you look at dance, it was so ephemeral,” Rojas said.

“Now, with TikTok, with technology, with pop culture, with me seeing ‘The Whoa’ on a t-shirt for a little four-year-old boy, that is not ephemeral anymore. That doesn’t go away; someone else is making money on that idea,” she said.

Logitech is financing the lawyers and fees associated with the copyright process for the 10 creators, which Rojas said could take anywhere from 10 weeks to three and a half months per copyright. The company is also working to apply the rights retroactively, like with the t-shirt Rojas saw at the store. They did not disclose how much they were spending for this initiative.

Copyright as social justice

Getting copyright protection for choreography can be murky. The regulations issued by the US Copyright Office explicitly say “the dividing line between copyrightable choreography and uncopyrightable dance is a continuum, rather than a bright line.”

On one end of the continuum are ballets, modern dances and other complex works. At the other end are social dances and simple routines. Knowing where TikTok dances and other choreography created by Black Americans fall on the spectrum can be unclear.

“Some people have argued that you could look at copyright and you could find some inherent racism in terms of what gets protection what doesn’t get protection,” Lateef Mtima, professor at the Howard University School of Law and the founder of the Institute for Intellectual Property and Social Justice, told The Plug.

He does not think the copyright language is intentionally racist, but that the people who wrote the regulations had a limited perspective on what social dance is compared to choreography.

“When you think about social dance, you think about something that is ritualistic, complex, conveying abstract messages to each other. When I was growing up in Harlem in the 60s and 70s, that description could fit a lot of what we did as dance,” Mtima said. “You look at other communities and you look at the way they dance, much of that dance is, shall we say, organic, freestyle — some people might characterize it as arhythmic.”

Mtima argues that social justice is an inherent mandate of copyright protection, though it has failed to live up to it in certain cases. Marvin Gaye, who did not read sheet music, was not able to receive full copyright protection for some of his compositions because the rules at the time only accepted written music notation, not song recordings. This was key in a recent trial involving Pharrell and Robin Thicke’s song “Blurred Lines,” who were found to have plagiarized a Gaye song.

Mtima said the intention behind copyright is to encourage artists to create work by giving them legal rights and the ability to profit.

“It has to be dependent upon principles of socially equitable access, inclusion and empowerment, because the only way that you will get the most and broadest product is if you encourage the most diverse group of people to participate,” he said.

It is a sentiment Rojas echoed. She hopes the example of copyrights for people like Keara Wilson and Young Deji can empower other creators.

“If they feel empowered in their creativity, I think we’ll see more innovation,” Rojas said.

However, copyright protects against reproduction or public performance without permission, potentially chilling how TikTok users may interact with a dance going forward.

Rojas said that is not the intent.

“It isn’t about people using it to spread it, because that is what makes it so special in the first place,” Rojas said. “The intention is if you want to use it in a commercial capacity, outside of the peer-to-peer network or social network, like you want to use it on Broadway, you want to put it in a film, you want to put it on a t-shirt, you need to ask me. I made this, you have to pay me.”

It is unclear, though, if copyrighting choreography conflicts with TikTok’s terms of service or if any of the creators would have to share profits with the app. TikTok did not respond to a request for comment, but Rojas said the company has been supportive of the work they are doing.

Mtima thinks copyrights for digital creators is a tremendous opportunity that not only allows for profiting off their work, but also gives them the ability to leverage online followings into new deals that allow them to evolve into mainstream celebrities.

Keara Wilson was overjoyed the night she learned about Logitech and Knight’s efforts to have her choreography copyrighted; she celebrated in the most appropriate way — with a TikTok video of her and Knight doing the dance that launched her career and a simple caption: “Savage Dance is officially COPYRIGHTED! I own my dance ”