The pervasive role of social media has ignited interest in the reformation of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a law that was initially enacted by Congress in an attempt to stop minors from accessing pornography on the internet. But a growing need to hold social platforms accountable for what happens in their spaces has resulted in talks of a law that could change the current form of the internet forever, thus ‘breaking the internet,’ has reached new heights.

Known as the “26 words that created the Internet,” Section 230 provides immunity for internet companies like Facebook and Twitter from being liable for user-generated content on their sites.

Section 230 was placed on the national stage after Twitter began placing warning labels on some of then-President Donald Trump’s tweets for spreading misinformation, which prompted the rallying cry “REPEAL SECTION 230.”

Many Republican politicians rallied behind Trump as they claimed social media companies discriminated against conservative voices online and sought to censor them, leading many to turn to Parler, an app where content goes completely unfiltered and uncensored.

Trump, who has been banned from Facebook and Twitter since January 2021 for the role he played in inciting violence and the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, issued another attack on the tech companies for silencing him. On Wednesday morning, he announced a class-action lawsuit targeting Facebook and Twitter and their CEOs Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey.

The debate about modernizing Section 230 has been discussed among internet policymakers for the past few years. Advocates for maintaining the law in its present form assert social media and other interactive websites would not exist without it. Calls for change cite how Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and other tech companies benefit from harboring and fostering offensive content without being held accountable for it.

Reforming Section 230 is on the agenda for both Congress and the Biden Administration, but how they plan to address it is still unclear. But while both appear to be in favor of increased content moderation, caution against changes to Section 230 has come with warnings of potentially ‘breaking the internet.’

“While the warning that regulation of technology may break the internet has been overused, ill-conceived changes to Section 230 actually could break the internet,” Cameron Kerry, Distinguished Visiting Fellow of the Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings, said in a post.

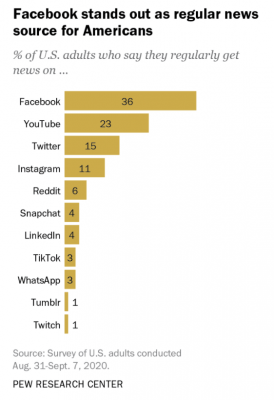

The growing reliance on social media platforms as a primary news source for many Americans is a central reason for talk of Section 230 reform. According to Pew Research Center, 36 percent of adults in the U.S. use Facebook as a regular news source.

The problem is not that nearly a third of Americans turn to social media for news content Rather, misinformation spreads across the platforms largely unchecked, unregulated, and unmonitored. Facebook has recently attempted to mitigate this problem by employing the Facebook Oversight Board, which aims to hold Facebook accountable for its content moderation.

In its current state, Section 230 promotes “self-moderation” without placing legal requirements on companies to monitor the information posted on their sites. Proposed reforms seek to require internet companies to decide what content posted on their sites is “true” and what is “false,” which treads into dangerous, hyper-censored territory.

Across the globe, authoritarian regimes rely on online censorship as a tool to silence critics, stifling social movements. The weaponization of censorship by such governments has shaped the lens through which some Americans view content moderation.

A study by Brado, in partnership with Invisibly, found that 52 percent of Americans believe there should not be any censorship at all, while 38 percent believe only some is permissible as long as it is limited.

The report found those “ok” with limited censorship are referring to “circumstances when violence or discrimination could be incited, or false information could be spread.” More notably, 91 percent of Americans are either partially or completely against censorship.

Following the murder of George Floyd last summer, TikTok users discovered posts with #GeorgeFloyd or #BlackLivesMatter hashtags were being suppressed by the platform. In June of last year, Vanessa Pappas, U.S. General Manager for TikTok, and Kudzi Chikumbu, Director of Creator Community, wrote in a blog post, “We acknowledge and apologize to our Black creators and community who have felt unsafe, unsupported, or suppressed.”

The post continued to say, “At the height of a raw and painful time, last week a technical glitch made it temporarily appear as if posts uploaded using #BlackLivesMatter and #GeorgeFloyd would receive 0 views,” they said.

Public pressure pushed TikTok to pursue meaningful actions to ensure social movements like Black Lives Matter would no longer be censored or appear to be censored on their app. The company announced plans to set up a “creator diversity council,” to promote conversations driving social change.

As proposals for Section 230 reform are being contested in Congress, there seem to be no explicit protections for social movements against censorship. While freedom of expression is embedded into the U.S. Constitution, online rights must be considered.

The assimilation of technology into daily life means social movements will continue to increase reliance on social media and other internet platforms. Without guaranteed safeguards for activism online, societal change becomes harder to pursue.

In pursuing Section 230 reform, Congress has the feat of acting in consideration of the Constitutional right to freedom of speech.

Sponsored Series: This reporting is made possible by the The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation

The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation is a private, nonpartisan foundation based in Kansas City, Mo., that seeks to build inclusive prosperity through a prepared workforce and entrepreneur-focused economic development. The Foundation uses its $3 billion in assets to change conditions, address root causes, and break down systemic barriers so that all people – regardless of race, gender, or geography – have the opportunity to achieve economic stability, mobility, and prosperity. For more information, visit www.kauffman.org and connect with us at www.twitter.com/kauffmanfdn and www.facebook.com/kauffmanfdn.